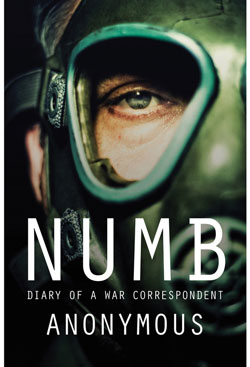

Who is Alan Buckby? According to Liberties Press, publishers of Numb: Diary of a War Correspondent, Buckby is the pseudonym of a 55-year old British foreign correspondent who was killed on assignment in 2014.

“A war correspondent for more than two decades, he led a double life, appearing to be a regular family man while at home in London, but immersed in sadism and depravity while on overseas assignments. He didn’t just document the violence – he became directly involved in it.”, the Liberties website blurb tells us excitedly.

Fun stuff, if you’re into that sort of thing. The ghostwriter, Louis La Roc, claimed that the materials for the book had come via a mutual friend from “Kay Buckby”, the wife of the deceased reporter.

Earlier this month, “Louis La Roc” appeared on two national radio stations in Ireland, luridly describing the contents of the book, to much criticism from Irish journalists. RTE’s Fergal Keane (not to be confused with the BBC’s Fergal Keane) dismissed the La Roc interview on the station’s John Murray show as “the biggest load of crap I have ever heard”, while the Irish Times’s Hugh Linehan called the interview (and by extension the book) “torture porn”.

Linehan invited Louis La Roc on the Irish Times’s Off Topic podcast on 18 April, where he and fellow Irish Times writer Patrick Freyne questioned him on the veracity of the details in the book. The timeline was, to put it mildly, all over the place. To give one example, in the book it is claimed that Buckby went to Northern Ireland in the early 80s because he was fascinated by British broadcasters’ ban on the broadcast of the voices of Sinn Fein and IRA spokespeople. In fact, that ban was only introduced in 1988. The author claimed that the various discrepancies in detail were introduced to protect the innocent, and that he had used a “cinematic jumpcut” technique to help the narrative along. Moreover, no one could find any evidence of a 55 year-old British foreign correspondent who died in late 2014.

The journalists questioned how long it had taken La Roc to write the book, from receiving the raw material to delivering to the publishers. Three months, apparently. When Freyne expressed surprise at this, La Roc suggested that it was about the same length of time as it took Siobhan Curham to work up Girl Online, the novel published under the name of vlogger Zoella that was one of last year’s best selling books, as if they were identical projects.

After the podcast, in which La Roc was openly accused of peddling fiction as fact, Freyne kept digging, and discovered that La Roc was more than likely the pen name of Colin Carroll, a self-promoter who had in the past, among other things, set up something called The Paddy Games and a website called Irish Empire. At one point he even had a joint BBC/RTE TV show, Colin And Graham’s Excellent Adventures (in the blurb for which, Colin and Graham are described as “sporting hoaxers”).

The coup de grace was delivered when another writer, Donal O’Keeffe, dug up a 2010 interview with Colin Carroll in a local newspaper, the Avondhu Press, in which he had said he was working on a novel with a war journalist as protagonist.

All in all, a very satisfactory bit of sleuthing for all concerned.

What happened next was interesting. Because what happened next was absolutely nothing. Numb is still out there, still listed under the non-fiction section of the Liberties Press website. The blurb still makes the same claims as it always has about the genesis of the book. The publisher is standing by the book, despite confirming that he made no attempt to verify the inflammatory information contained within. Perhaps defiantly, a quote from Oscar Wilde hovers at the top of the page: “There is no such thing as a moral or immoral book. Books are well written or badly written. That is all.”

It is as if…it is as if this is the kind of story that only journalists really care about (and you, dear reader, considering you’ve made it nearly 700 words into this piece. But you’re probably a hack too, aren’t you?).

And that is something that should give journalists pause for thought. Do people see us as we see ourselves? And do people put the same value on accuracy and truthfulness as we claim to?

Think of the great journalistic scandals of the past few years: when the story broke of Johann Hari’s fabrications and sockpupetting back in the summer of 2011, journalists talked about little else among themselves. Really, seriously, nothing else for about a month. But were Hari’s Independent readers camped outside Northcliffe House, furiously demanding apologies and clarifications from the paper and Hari himself? No. Non journalists I spoke to about the issue didn’t really understand what the fuss was about.

Or think of Jonah Lehrer, who made up quotes. Sure, like Hari, he was eventually dropped by employers, but did his readers really care that he’d put words in Bob Dylan’s mouth?

Meanwhile, online activists (not naming any names) spread all sorts of nonsense that gets more shares than many social media managers could dream of, because it contains that magical element of “truthiness”, to borrow a phrase from Stephen Colbert: it tells people what they want to hear. Just last week, lots of left wingers got terribly excited about a headline for a column in the Times which said that the Conservatives had got the economy wrong. “Wow ! The Times newspaper nails the Tory Lib Dem lie about the deficit & the financial crisis.” tweeted Michael H, with an accompanying picture of the headline “It’s a lie to say the Tories rescued the economy”. The tweet spread like wildfire, with the subcurrent being that EVEN THE MURDOCH PRESS was backing Labour now. The fact that the headline accompanied a guest column by a Labour peer seemed not to matter. The people sharing wanted it to be an attack on the Conservatives by the Murdoch press, and so it was.

It was the same desire for truthiness that fed the likes of Hari, and to an extent, feeds the publishers of Numb. It was what led Piers Morgan to publish photographs allegedly showing British soldiers torturing Iraqis, even though they were obviously false.

And I suspect it was behind Liberties Press decision to publish the “torture porn” of Numb: it felt like the kind of thing that might just be real.

It is important that journalism realises its duty to entertain and not just hector (not all journalism is, or should be, the “investigative journalism” so lionised by Royal Charter-waving groupies as the true untainted thing). But journalism should at least, be against truthiness, if only out of self interest. If anyone can make stuff up and get 1,000 shares on Twitter, why pay people for deep digging or elegant writing?

But consumers of media have a role to play in this too: everyone should be actively alert to the difference between stuff that is true and stuff that merely feels right, and not encourage the latter. As George Orwell wrote: “We shall have a serious and truthful and popular press when public opinion actively demands it.”

This column was posted on April 23 2015 at indexoncensorship.org