(Image: edward123456789/YouTube)

I still laugh every time I think of the funniest thing I’ve ever said, even though it was about 18 years ago.

Trouble is, I can’t tell you what it was. It was in rather poor taste. It was of such you-had-to-be-there nature that there would be literally no point in repeating it, then explaining it, then justifying it, then eventually apologising because you know, honestly, you’re right, it was in poor taste.

It was still funny though.

Jokes are unbelievably precious things, which is why they’re taken so seriously. Aside from actual touching, the most intimate unguarded moments we have with people tend to involve laughter.

Which is what makes the whole idea of comedy kind of odd. We pay professionals to provide us with our moments of joy, of sheer unthinkingness.

But for all the rapture of laughter, jokes are also extremely complicated, and mired in context. Like music, there comes the inevitable point where one decides that what one thinks is funny is funny, and what isn’t isn’t. What isn’t, is usually what comes after one’s own peak of interest.

So, everyone knows that the first nine or ten series of the Simpsons were solid comedy gold.

By everyone, I mean, for the most part, males between 32 and 45, who can easily bond over Simpsons quotes at otherwise awkward parties.

For many, Seinfeld performs the same function, an infinite mine of references and in-jokes. It’s a show I came to a bit late, and I can sometimes shout “No soup for you” and get a laugh, but my heart’s not quite in it in the same way as when I make the Sideshow-Bob-stepping-on-a-rake noise.

Still, Jerry Seinfeld is part of my comedy world, his comedy part of a particular golden age of 90s US sitcom that as well as the Simpsons and Seinfeld, spawned Friends and Frasier (less cultishly adored, perhaps, but very successful) and a host of less impressive impersonations.

Jerry Seinfeld, in comedy terms, is still important.

So it was of note when he recently told a US chat show that “PC” culture made him wary of playing university campuses.

Seinfeld gave the example of a joke about people’s obsession with staring at their smartphones: “They don’t seem very important, the way you scroll through (your phone) like a gay French king.”

The comic suggested that he could feel the audience’s nervousness about the deployment of the word “gay” in the gag. “[C]omedy is where you can feel an opinion. And they thought, ‘What do you mean gay? What are you talking about gay? What are you doing? What do you mean?’”

I feel some sympathy with Seinfeld here. We all know the feeling when a line we thought was perfectly good just drops, clangingly, to the floor and then through it, to hell: the feeling must be magnified a thousand times when you are used to getting laughs, and when getting laughs is what you do for a living.

But honestly, I also kind of feel for the crowd. Jokes about people staring at their phones do not really constitute cutting-edge humour in 2015. In fact, Seinfeld’s joke provokes approximately the same melancholy as the phrase “Brand new Simpsons” (“Homer has an argument with FKA Twigs on Twitter! This is going to be brilliant!”), turning us all into Comic Book Guy (“Worst. Topical reference. Ever.”)

But is Seinfeld entirely wrong? There is probably some truth in the idea that so-called “social justice activists” are a little too keen on policing speech, and not massively enthusiastic on the mildly transgressive nature of comedy of the type Seinfeld deals in.

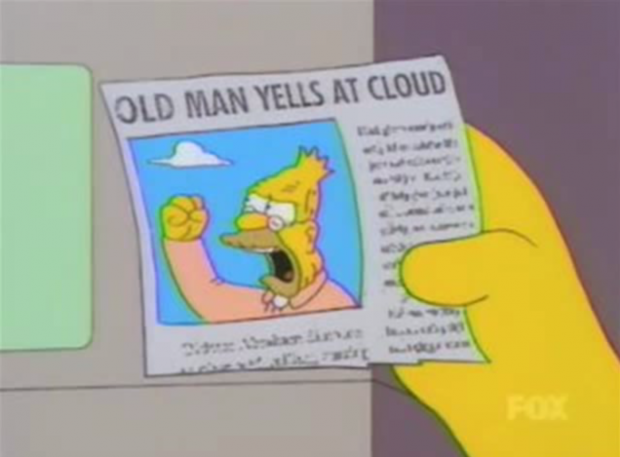

There is also the more basic point that people are more forgiving of people they like. It’s possible that, say, the universally-adored Amy Poehler could have made the same joke and got a different response. But then, would she have made the same joke? Unlikely. Much like his PC complaint, it has a bit of an Old Man Yells At Cloud feel about it (See? Simpsons references are great).

Every so often (roughly generationally) there are upheavals in mores and language. We’re on that cusp now. When I was younger, the battle was to stop people saying words like “coloured” (and much, much, worse) and move on to “black”. Now, we’re moving towards “People of Colour” [POC]. This isn’t a tearful lament for the good old days when “gay” meant “carefree” and no one really thought about who Larry Grayson slept with. I retain just enough self-awareness to avoid that. And besides, it’s a ridiculous lie. No one tuning into the BBC’s Round The Horne in the 1960s, for example, was under any illusion about Polari-spouting Julian and Sandy’s references and double entendre. Much of the delight for many listening was a glimpse into the previously closed (criminalised) world of gay subculture, recently brought into the light in the debates following the Wolfenden report, which had recommended a relaxing of anti-gay laws.

The problem that the likes of Seinfeld and me, a bit, have is that we resent the implication we’re wrong when we think we are, at very worst, out of step. We (I’m sure Jerry won’t mind me speaking for him here), believe we’re pretty much good people. And people should know we’re good people. Jerry Seinfeld is sure people should know he’s not homophobic, so is a bit freaked out when people get uncomfortable with him using certain words in certain contexts. But not everyone does know him, and not everyone is totally on board. Is their disapproval censorious?

Probably a bit, yes. In the same way yours would be if I told you the funniest thing I’d ever said. And, I suspect, as I would be if you told me about the things you and your closest friends laughed longest and loudest about. Funny is about how and when and who with. Comedy is all about…timing.

This column was posted on 18 June 2015 at indexoncensorship.org