[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This guide is also available as a PDF.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Preface

Freedom of expression is essential to the arts. But the laws and practices that protect and nurture free expression are often poorly understood both by practitioners and by those enforcing the law. The law itself is often contradictory, and even the rights that underpin the laws are fraught with qualifications that can potentially undermine artistic free expression.

As indicated in these packs, and illustrated by the online case studies – available at indexoncensorship.org/artandoffence – there is scope to develop greater understanding of the ways in which artists and arts organisations can navigate the complexity of the law, and when and how to work with the police. We aim to put into context the constraints implicit in the European Convention on Human Rights and so address unnecessary censorship and self-censorship.

Censorship of the arts in the UK results from a wide range of competing interests – public safety and public order, religious sensibilities and corporate interests. All too often these constraints are imposed without clear guidance or legal basis.

These law packs are the result of an earlier study by Index: Taking the Offensive, which showed how selfcensorship manifests itself in arts organisations and institutions. The causes of self-censorship ranged from the fear of causing offence, losing financial support, hostile public reaction or media storm, police intervention, prejudice, managing diversity and the impact of risk aversion. Many participants in our study said that a lack of knowledge around legal limits contributed to self-censorship.

These packs are intended to tackle that lack of knowledge. We intend them as “living” documents, to be enhanced and developed in partnership with

arts groups so that artistic freedom is nurtured and nourished.

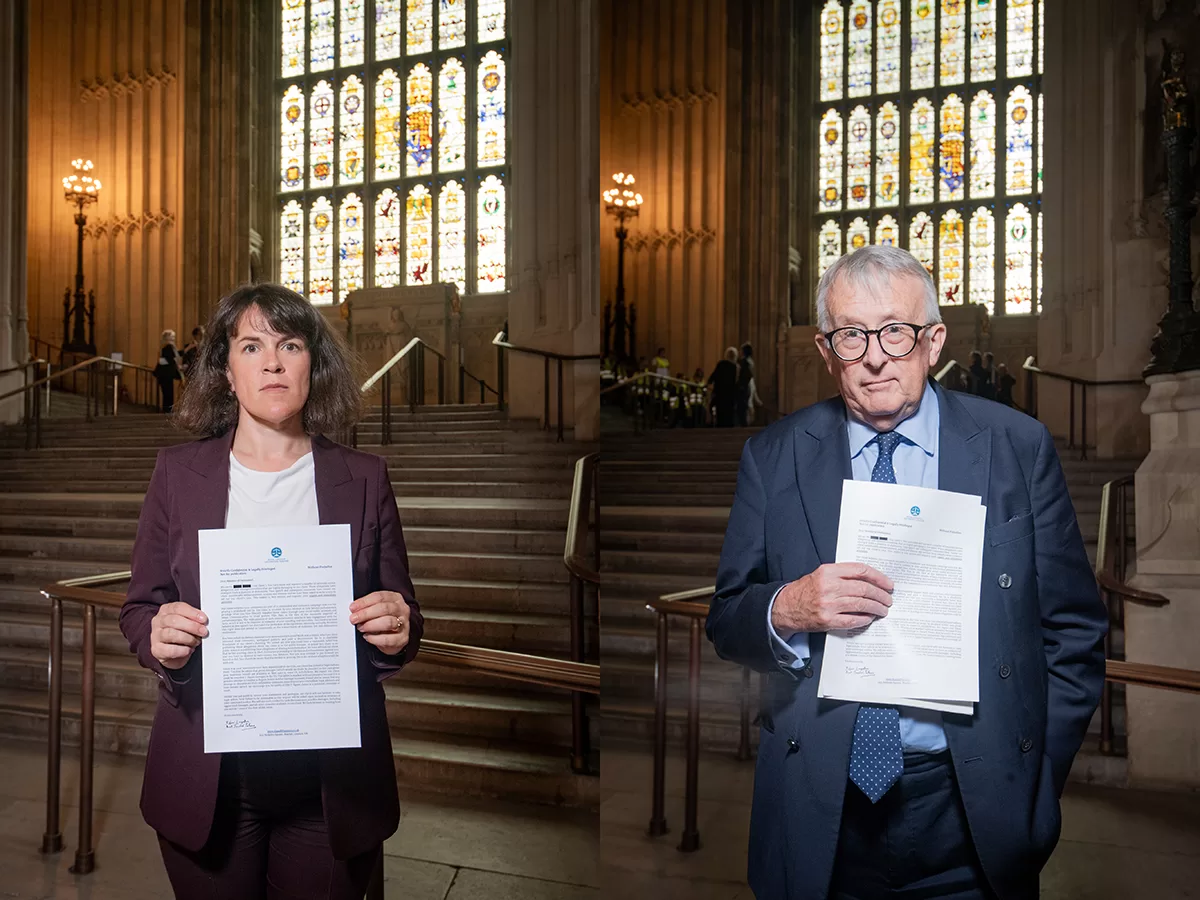

Jodie Ginsberg, chief executive, Index on Censorship

Foreword by Brett Rogers

I was surprised when I arrived at The Photographers’ Gallery in 2005 to discover there had never been a solo show of US photographer Sally Mann in the UK. So when I saw the touring exhibition, The Family and The Land, in Amsterdam, I decided to bring it to London.

In Holland and Scandinavia there had been no controversy surrounding the exhibition, but here in London, even before the show opened, we were caught up in a sudden, unexpected and distressing legal storm.

Suddenly, we were being told we risked arrest if we brought the work into the country: if convicted, we were told, the artistic team could find themselves on the child sex offender register and if Sally Mann stepped off a plane she might be arrested. It all escalated rapidly, so we were extremely relieved when it was equally quickly resolved after we took advice from lawyers.

During this furore, I stood by the show, determined to support the artist’s rightful role in engaging with children, especially a mother depicting her own children. I wanted the exhibition to oppose the reading of images of children which forces us to look through the eyes of a paedophile and ask: “If we had this or that mindset would we be aroused?”.

To me this is completely the wrong way for the public to approach these images. I wanted to invite the audience into the gallery to see what Sally Mann does so poetically in her work – depicting the lyricism and the lost innocence of children, but also the difficult transition from infancy to adolescence, creating a rounded portrait of childhood in the late 20th century.

Photographers are often drawn to very intimate subjects and have a way of approaching taboos that is important for us to see. Taboos need to be talked about, so for me the largely very constructive and positive debate in the media surrounding the show, especially about the role of women in photography was the best thing, moving as it did to the news pages and out of the niche of the art community talking to itself. Opening up that debate is what art should do, because to close it down or throw a veil over taboo subjects allows misinterpretations to be perpetuated.

Brett Rogers is artistic director of The Photographers’ Gallery, London.

(Brett Rogers was interviewed by Julia Farrington)

Freedom of expression

Freedom of expression is a UK common law right, and a right enshrined and protected in UK law by the Human Rights Act*, which incorporates the

European Convention on Human Rights into UK law.

*(At the time of writing (June 2015), the government is considering abolishing the Human Rights Act and introducing a British Bill of Rights. Free expression rights remain protected by UK common law, but it is unclear to what extent more recent developments in the law based on Article 10 would still apply.)

The most important of the Convention’s protections in this context is Article 10.

| ARTICLE 10, EUROPEAN CONVENTION ON HUMAN RIGHTS1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This article shall not prevent states from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises.

2. The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary. |

It is worth noting that freedom of expression, as outlined in Article 10, is a qualified right, meaning the right must be balanced against other rights.

Where an artistic work presents ideas that are controversial or shocking, the courts have made it clear that freedom of expression protections still apply.

As Sir Stephen Sedley, a former Court of Appeal judge, explained: “Free speech includes not only the inoffensive but the irritating, the contentious, the eccentric, the heretical, the unwelcome and the provocative provided it does not tend to provoke violence. Freedom only to speak inoffensively is not worth having.” (Redmond-Bate v Director of Public Prosecutions, 1999).

Thus to a certain extent, artists and galleries can rely on their right to freedom of expression under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights: the right to receive and impart opinions, information and ideas, including those which shock, disturb and offend.

As is seen above, freedom of expression is not an absolute right and can be limited by other rights and considerations. While the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and police have a positive obligation to promote the right to freedom of expression, they also have a duty to protect other rights: to private and family life, the right to protection of health and morals and the protection of reputation.

They also have the a duty to protect the rights of the child, meaning the right to freedom of expression may be subject to legal restrictions necessary to protect the rights of children. Artists and galleries who make or display works using children that could be considered obscene or indecent, should consider the ways in which the works advance the public interest and prepare well, so as to be in a position to defend their work and show that the rights of the children involved have been considered.

The following sections of the pack look at one element of the law that may be used to curtail free expression: child protection legislation.

Child protection offences explained

Child protection is a sensitive area of law and a deserved focus of public concern. The prospect of a police investigation alone will be a matter of substantial press interest, while an actual prosecution, although unlikely in the professional arts sector, would nevertheless result in grave consequences for the gallery and the artist. As there is no clear legal definition of the concept of indecency, and because of the sensitivity of the matter, decisions made by the police and Crown Prosecution Service can be subjective and inconsistent, and in the wrong context can seriously compromise freedom of expression rights. For that reason, it is important to be aware of the legal framework and to take practical preparatory steps at an early stage.

The offences proscribed by the law cover a broad spectrum of behaviour. If you make or display or possess a work involving images of children that could be considered to be, or is indecent, obscene or pornographic, you may be committing a serious criminal offence. The circumstances or motivation of a defendant are not relevant to determining whether or not the image is indecent. The work may be seized, and the gallery, its directors and staff and the artist may risk arrest and/or prosecution. Information about an investigation, arrest or prosecution can be kept and may be legally disclosed to others by police in certain circumstances. Convicted people may be treated as sex offenders depending on the seriousness of the charge.

The UK laws that could be used to prosecute artists in relation to images of children include:

• The Protection of Children Act 1978 (PCA), which prohibits making, taking, permitting to be taken, distributing or showing indecent photographs or “pseudo-photographs” of children (including film or computer data such as scans) http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1978/37/contents. “Pseudo-photographs” are defined as “an image, whether made by computer graphics or otherwise, which appears to be a photograph”.

• The Criminal Justice Act 1988 (CJA), which creates an offence of possession of indecent photograph or “pseudo-photograph” of a child http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/33/contents

• The Coroners and Justice Act 2009 (COJA), which criminalises the possession of nonphotographic images of children which are pornographic and grossly offensive, disgusting or otherwise of an obscene character http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2009/25/contents

• Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act 1955 http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Eliz2/3-4/28/introduction

• Indecent Displays (Control) Act 1981 (IDCA) http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1981/42/contents

• Obscene Publications Act 1959 (OPA) http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Eliz2/7-8/66/contents

• Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE) http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1984/60/contents

These laws are intended to protect the rights of children. The police and prosecuting authorities should also consider the free expression rights of artists and galleries under the European Convention on Human Rights when making a decision about whether to investigate or prosecute.

Galleries and their officers or directors and artists could commit a criminal offence under the Protection of Children Act in relation to indecent photographic, film and pseudo-photographic images including tracings. For a photographic or film image to be considered indecent under the law, it must be found to offend recognised standards of propriety. This is an extremely fluid test that changes along with society’s changing expectations.

In relation to non-photographic or film images, the Coroners and Justice Act criminalises the making and display and possession of non-photographic images which are pornographic, grossly offensive or disgusting and focused on the anal or genital region of a child, or show certain specific sexual acts.

So, a photograph of a naked child in a room full of clothed people could be considered indecent under the Protection of Children Act. There would be a different and higher test under the Coroners and Justice Act for a drawing, painting or sculpture. For example, a drawing of a 14-year-old masturbating could well be considered unlawful.

The circumstances or motivation of the artist or gallery are not strictly relevant to the test, and the standards of some members of the public and some police officers may differ from your own. If you are to defend successfully your position and exhibit works that are controversial but not harmful, you need to recognise this potential problem in advance. Take clear steps to contextualise the works and be ready to demonstrate why they should not be treated as indecent.

If the Crown Prosecution Service does decide to prosecute, there are very limited defences available. In the case of possessing, making or taking indecent photographs of children – prohibited under the Protection of Children Act and the Criminal Justice Act – the gallery or artist would have to demonstrate that they had not seen the images and had no reason to suspect they were prohibited, that the images were of a person over 16 to whom the artist was married or in a civil partnership, or that they had a “legitimate reason” for being in possession of them or distributing them.

The concept of “legitimate reason” has not been tested in the context of art, but current guidance by the Crown Prosecution Service and the leading case (Atkins v Director of Public Prosecutions) suggests that in a non-artistic context it applies only in very restricted circumstances, such as when it is necessary to possess the images to conduct forensic tests or for legitimate research. It also suggests that any court should approach such a defence with scepticism.

In relation to non-photographic images, the artist/gallery may be able to argue at an early stage that the images were not pornographic by careful contextualisation. This does not always work, but the more thought put into it at an early stage, the better.

As stated above, to a certain extent artists and galleries can rely on their right to freedom of expression under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights: the right to receive and impart opinions, information and ideas, including those which shock disturb and offend. That right is qualified by the need to protect the rights and freedoms of others.

In the context of child protection, the rights of children not to be exploited and those of a young audience will be set against the right to freedom of expression. That means the police and courts are permitted in some circumstances to act in ways that will compromise the freedom of expression rights of artists. Any decision they make will require these competing objectives to be balanced. The Crown Prosecution Service must reasonably consider that it is in the public interest to bring a prosecution.

If the images you are making raise issues about child protection, allowing for the heightened sensitivity about children under the law, then the balance may fall against freedom of expression. If an artist is prosecuted for any of these offences, the consequences could be very serious for him or her personally and for freedom of expression more widely. For all these reasons, it is advisable to prepare well and challenge early.

The powers of the police and prosecuting authorities

The police have the right to enter and search galleries and to seize artworks in certain defined circumstances. Under Section 8 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act, a magistrate may issue a warrant to search premises if a serious arrestable offence has been committed. Under Section 19 of the same act, police may seize anything that is on the premises if they have reasonable grounds for believing that it has been obtained in consequence of, or is evidence of, an offence. The police must be on the premises lawfully – either with a warrant or attending an exhibition that is open to the public, or invited in. In most cases the police enter galleries following a complaint by a member of the public or the press.

Under Section 4 of the Protection of Children Act a judge may issue a warrant authorising the police to enter and search premises and seize any articles that they believe with reasonable cause to be, or include, indecent photographs of children. Under Section 67 of the Coroners and Justice Act, Section 4 of the Protection of Children Act also applies to images of children other than photographs, and digitally adjusted “pseudo-photographs”.

Police can seize an art work and recommend it be removed without having established a watertight case. All that need be established is reasonable grounds for believing the relevant crime has been committed. In some cases the advice or presence of the police may put pressure on the gallery to remove an artwork voluntarily. However, a gallery is not obliged to remove an artwork because the police have merely advised it to do so (rather than seizing the work). The police may be taking an overly conservative approach and their interpretation of the law may be wrong. The gallery should, therefore, seek independent legal advice before permanently removing artworks, and inform the police that they are doing so.

Prosecutions under the Protection of Children Act require the consent of the director of public prosecutions (DPP). In all cases the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) will adopt a three stage approach before deciding whether or not to prosecute. First, they will consider whether or not an offence has been committed. Secondly, they will consider whether there is a realistic prospect of conviction, including if the image is indecent in the case of photographs, or the higher test for nonphotographic images, and whether there is any defence that is likely to succeed. In the context of child protection these defences are very limited. If there is enough evidence, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) will proceed to the third stage and consider whether it is in the public interest to prosecute, taking into consideration the competing rights of the artist or gallery and others, including children. A reading of the Crown Prosecution Service code which governs its decisions and its list of public interest factors suggests that there will be a lower threshold for prosecutions involving offences against children.

Practical guidance for galleries and artists

As good practice, you should institute a child protection policy that sets out the way you will handle controversial exhibitions where child safety issues might arise. This could be drafted with the help of legal or other professionals with experience in freedom of expression and it can be helpful to consult the police/local authority on best practice in general terms. Make sure you look at the local authority child protection policies and consider contacting the appropriate person in the local authority.

Where possible, establish good relations with the appropriate police officer responsible for child protection in your area. Such contacts should be routine for any public premises where children are admitted for participatory activities. A good relationship could be invaluable at a later stage. This is particularly important where controversial works are to be exhibited in communities where exposure to challenging or controversial art is less routine, or where officers are unused to the consideration or application of Article 10 rights to issues of policing.

If you are exhibiting any specific photographic images of children that might be considered indecent, or paintings or drawings that might be considered “pornographic, grossly offensive, disgusting or obscene” and which focus on the genital region or sexual acts, you should take the following steps:

• If you think the work may be borderline or cross over the line it is best to take legal advice so that you can be advised on the risks. Remember, when you are considering whether or not to take advice at this early stage you need to consider the likely standards of local community members and the local police, not your own.

• If you have good relations with the local police, it can be helpful to discuss issues arising in relation to specific work in advance. You can show the police the record of your decision-making process. You may decide to seek their assistance in determining whether or not there should be an age limit for the event though this will not always be appropriate and is not an alternative to the steps outlined here. Do not ask the police for advice on the content of the work, and do not seek “permission” to exhibit, which they cannot grant anyway.

• You should make a clear written record of the reasons for exhibiting the work relating to its artistic value, the steps you have taken to mitigate any potential harm and your decision-making process (see Appendix I for an example).

The issues to consider include:

• Why you consider the work to have artistic merit – context about the nature of the artist, what he or she is seeking to achieve, their previous work, the role of controversy in their work etc. If the artist is unknown or does not have a substantial body of work to which to refer, you should put the work and the artist in a wider context.

• The public interest in this work and freedom of expression itself, including in controversial or offensive work. Be prepared to make your motivation and reasons for making or displaying the work clear.

• The factors to be balanced against the right to freedom of expression, including the level of offence or harm that might be caused to a young audience and steps you have taken to mitigate it.

• You may choose to warn the audience that some images are not suitable for children/are sexually specific. Occasionally entrance to an exhibition may be restricted to those over 16 or over 18.

• Consider the potential harm to the subjects of the work – consider the age and welfare of any children involved and make sure that the children and parents/guardians have given informed consent in writing and that they have been properly supervised during the making of the work. The younger the child, the more important this factor is. Informed consent means making sure that the children/parents know how the work is to be used and have consented to it being publicly displayed. Be aware that consent does not in itself offer protection against prosecution, but will assist in combination with the other recommended steps. The gallery should obtain and keep copies of these consents. See Appendix II for pro forma consent form.

• Demonstrate an awareness of previous similar displays that have not been closed down. You should also keep abreast of reactions to recent art works and remain aware that the legal test of indecency relates to current recognised standards of propriety – which as noted earlier, is a fluid test.

• If you are contacted by the police, or if the police seek to remove a work, seek specialist legal advice.

Following the steps set out above will put an artist or gallery in a much stronger position to defend their right to make or exhibit controversial works involving children by demonstrating that they have behaved reasonably, considered the welfare of children and by contextualising the work.

Challenging a decision to investigate, seize work or prosecute will require specific legal advice and so is beyond the scope of this guidance, but in summary you may be able to:

• Argue that a police investigation, or a decision to seize works is a disproportionate interference with the right to freedom of expression and, if appropriate, institute judicial review proceedings so that a court can determine the lawfulness of the decision or decision making process.

• Argue that a decision to prosecute is a disproportionate interference with the right to freedom of expression, and/or a breach of the Prosecutors Code or otherwise unlawful and, if appropriate, issue judicial review proceedings.

• Argue that the decision to prosecute or charge is not in the wider public interest, or that the work is not in fact indecent or obscene.

Preparing well is crucial to any successful challenge.

Questions and answers

Q. What is the difference between Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights and Article 19 of the UN Declaration on Human Rights?

A. Freedom of expression, as outlined in Article 10, is a qualified right, meaning considerations regarding its protection must be balanced against other rights and interests. Article 19 of the UN Declaration on Human Rights, which also addresses freedom of expression, is less qualified: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers”. Nevertheless, even within the UN Declaration there are provisions which contemplate some qualification of the freedom expressed in Article 19. It is the European Convention on Human Rights which is currently relevant to UK law.

Q. Can I challenge a decision by a local authority or police body?

A. Yes. The usual way of doing so would be via judicial review. You should seek specialist legal advice before bringing your claim. Be aware that you must bring your claim as soon as possible and in any event no later than three months after the decision you wish to challenge. Judicial review is not ordinarily an effective means of overturning decisions quickly. Claims often take many months to be heard. However, it is possible to apply for a claim to be heard quickly if there are good grounds to do so. Even if you succeed you will not usually recover damages: they are awarded at the court’s discretion. The court might quash the decision under challenge, and/or require the public authority to adopt a different procedure in its decision-making.

Q. Does it make a difference if the display is outside the gallery?

A. In addition to legal restrictions under the Protection of Children Act and the Coroners And Justice Act, outside displays could also expose an artist to liability under the Indecent Displays (Control) Act 1981 (IDCA). The Indecent Displays (Control) Act does not apply to displays in an art gallery or museum and visible only from within the gallery or museum. However, a display projected onto the outside wall of a gallery would not be covered by this exception.

Q. How do the Crown Prosecution Service and the courts decide if an image is indecent?

A. A photographic image is considered indecent if it offends against recognised standards of propriety. That concept of recognised standards of propriety has been developed through case law, most recently in R v Neal (2011), which has described the recognised standard of propriety as a fluid test of indecency, changing according to society’s expectations.

Q. What levels of indecency are considered in prosecution of images of children?

A. There is no statutory definition of an indecent image in the Protection of Children Act – see the discussion in the R v Neal case. If there has been a successful prosecution and the jury have decided the image is indecent, the Court should apply sentencing guidelines which categorise indecency in the following way:

Category A

Images involving penetrative sexual activity and/or images involving sexual activity with an animal or sadism

Category B

Images involving non-penetrative sexual activity

Category C

Other indecent images not falling within categories A or B

Q. What are the legal issues affecting the relationship between artist and gallery?

A. Under the Protection of Children Act, the gallery may face prosecution for distributing or showing offending images, whereas the relevant offence in relation to the artist would be making or taking the offending images. Both could be prosecuted for possession with a view to the images being distributed. The time when the artwork is most likely to come within the radar of the police is when an exhibition opens. At this time the concern is with the artwork being in the public domain and the risk of prosecution tends to be faced primarily by the gallery. The defences for the artist if he or she is charged with making or taking the image are more limited than those for a gallery. The reason is that the person making an obscene image of children is usually considered more culpable than those who have secondary responsibility – publishers, disseminators etc, who might in some circumstances have a “legitimate reason” defence.

Q. Does artistic merit impact the extent to which an artist’s freedom of expression will be protected?

A. It is usually more likely that a gallery or artist will be permitted to display controversial works if they are well known and if it is generally considered that the work has artistic merit. This is something which may not be obvious to some non-specialist police officers and so it is important that you make early contact in order to contextualise the work and explain its importance.

This did not protect Richard Prince’s Spiritual America from being removed from Tate Modern’s exhibition POP LIFE in 2009 (for more about this case visit

indexoncensorship.org/artandoffence).

Q. What test does the CPS apply to art works whether to prosecute?

A. As outlined above, the concept of recognised standards of propriety has been developed through case law, most recently in R v Neal (2011). In that case Mr Neal was prosecuted and convicted for possession of books of photographs by Sally Mann among others. The Court of Appeal overturned the conviction on the basis that the jury was misdirected by the judge about the objective standards to be applied when assessing whether or not a work is indecent. The cases in which the concept has been discussed have not concerned artists, however the standard has been applied by the Crown Prosecution Service to controversial art in considering whether a prosecution should be brought.

Q. What defences does the gallery potentially have?

A. It can be very difficult to establish a defence under the laws that are intended to ban child pornography or other publications harmful to children. Although there is a “legitimate reason” defence in the Protection of Children Act, it can only be relied on in very limited circumstances and has never been used in the context of a prosecution of an artist. If a gallery has taken the steps recommended in this guidance to ensure children and young people are protected, and behaved responsibly throughout, there are reasonable prospects of heading off a prosecution, or convincing a jury that the work was not indecent or obscene or that a defence should apply. However, relying on a defence to criminal charges in this area must be a last resort and you will need specialist legal advice tailored to your own circumstances.

Q. What decisions are the police able to take and how can they implement these decisions?

A. The police have powers to investigate and to seize artwork depicting children under Section 19 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act and Section 4 of the Protection of Children Act if they have reasonable grounds for believing it offends the Protection of Children Act or Coroners and Justice Act. The Coroners and Justice Act includes a prohibition on possession of nonphotographic images of children, which are pornographic and grossly offensive, disgusting or otherwise of an obscene character. Images must also either focus solely or principally on a child’s genitals or anal region or depict a specified range of sexual acts (e.g. sexual activity with or in the presence of the child, masturbation, etc.). The Protection of Children Act criminalises the taking, possessing or displaying of indecent photographs of children.

Q. What potential measures can gallery directors take if the police try to seize artworks?

A. Gallery directors could argue that they have a “legitimate reason” for distributing, showing or possessing the photograph, although as stated above, you should take advice as the penalties are potentially very significant and the defence is untested in this context. Note that this would not apply to the artist for taking/making the photograph. If the police advise you to remove the works or to close the exhibition, you can argue that the advice is inappropriate or that you have good reasons for proceeding with the exhibition. If you have documented the reasons for exhibiting the photographs or paintings and obtained full consent from any children/parents, and established good relations with child protection officers, you will be in a stronger position to ensure that the exhibition can go ahead. Be careful about resisting physically or engaging in a heated debate with officers who could then arrest you for obstruction.

Q. Does the nature of the work (e.g. being a drawing rather than a photograph) impact the extent of an artist’s freedom of expression?

A. The tests for whether the making or displaying the work is a criminal offence are different depending on whether the image is a photograph in which case the Protection of Children Act applies or a painting or drawing in which case the Coroners and Justice Act applies. Displaying a photograph of a naked teenager standing alone in a field might create criminal liability (on the basis that it is considered by a jury to be indecent – the Protection of Children Act test), whereas displaying a painting of a naked teenager in similar circumstances would probably not (as it does not focus on the genital or anal region and is not grossly offensive, pornographic or obscene – the Criminal Justice Act test). Both rely on a jury’s understanding of what is indecent or obscene. Neither concept is clearly or succinctly defined in UK law.

Q. Can the police visit the gallery as a member of the public?

A. Yes, the police can visit the gallery. If they consider that an offence has been committed, they can obtain a warrant to enter and seize works.

Q. If an arts organisation or artist has sought legal advice does it have to follow it?

A. No lawyer is going to guarantee immunity or absolute safety from the law. In the best case scenario the lawyer will advise on the law and make it absolutely clear that it is your decision and your responsibility to decide how to act. It is the gallery and the artist who are going to have to make up their minds to take the risk or not.

Q. Do you have to follow the advice of the first lawyer you approach?

A. Research the lawyers who have they dealt with these specific issues – look at their track record to see if they are able to support you. You can always seek a second opinion from another lawyer if you are unhappy with the advice, although it is likely to be expensive.

Q. Could following the advice in this pack to establish good relations with the police encourage self-censorship given the police’s role in ensuring that neither artist nor gallery inadvertently break the law or cause any offence to their visitors?

A. Establishing good relations is not the same as avoiding offence – if you explain your purpose to the relevant people then you are in a much stronger position further down the line.

Q. Do I have to give the script of a play or images I intend to exhibit to the police or local authority prior to the show opening if requested?

A. You only have to provide a copy of a script (or any document or property) if the police or local authority has a legal power to view and seize that material.

Accordingly if a local authority or the police ask to see particular artistic material you should ask them to clarify whether they are demanding that you hand over the material, or whether they are simply asking for your voluntary co-operation. If they are demanding that you provide the material, ask them to identify the legal power that gives them the right to do this and ask to see a copy of any order made.

You should make a contemporaneous note of their answers. If the police are simply seeking your voluntary co-operation then you do not have to give them anything. If in doubt about the scope of their powers, consult a lawyer.

Appendix I: Documenting and explaining a decision

Please note: Appendices are examples only and not a substitute for legal advice.

Example: A gallery seeks to exhibit photographs of naked and semi-naked children in provocative poses taken by a well-known photographer who has previously exhibited photographs of clothed children in similarly provocative positions. The gallery owner decides the work has value and should be exhibited.

The decision may be documented as follows:

Reasons for the decision

1. The artist seeks to challenge the boundaries of photographic depictions of children on the edge of puberty and to respond to advertising aimed at young children and expose hypocrisy in the market for children’s clothing.

2. This work is made in response to a debate of general public interest – society’s approach to the portrayal of children’s bodies in different contexts.

3. The work has artistic merit and the artist has sold/exhibited numerous copies of previous works that have been positively reviewed (give examples) and has works in major art collections.

4. There is a public interest in freedom of artistic expression itself and we consider that this is work of value which should be seen exhibited and viewed so as to further an important debate.

5. We recognise that there is a risk the work may be misunderstood by some individuals and so cause undue offence or cause them to be concerned that the needs of children have not been considered and protected. Accordingly, we and the artist have taken steps to ensure children are adequately protected including:

a. We have confirmed that all the children involved in the photography were properly supervised by parents or those with parental responsibility while the photographs were taken and that informed written consent was given and the artist has confirmed this in writing.

b. We have considered whether or not our advertising material should contain warnings that the exhibition contains images which could offend.

c. We have considered whether or not we should issue advice or put a warning on the entrance to the gallery that the show is not suitable for children under 16/18.

d. We have carefully considered our own child protection guidance policy (and/or that of the relevant local or other authority) and are confident that the work falls within our policy recommendations.

Appendix II: Pro forma consent form

I, [name], the parent/guardian of [name] hereby consent to the taking of photographs of [name] by xxxx to be used in the artistic work xxxx and to be exhibited publicly in galleries and reproduced for publicity purposes in any medium including on websites.

[I recognise that these photographs involve nude and semi-nude poses/will form part of a work which includes violent images/etc]. (Delete as necessary)

I [name of child if over 12] also consent to such photographs being taken of me and used in the artistic work xxx and exhibited to the public in any gallery, and in any accompanying publicity material, including on websites.

Signed and dated

Acknowledgements

This information pack was produced by Vivarta in partnership with Index on Censorship and Bindmans LLP.

The packs have been made possible by generous pro-bono support from lawyers at Bindmans LLP, Clifford Chance, Doughty Street, Matrix Chambers and Brick Court.

The packs have been designed and printed by Clifford Chance, Greg Thompson, Design Specialist, Document Production Unit

Art & the Law -Child Protection -A Guide to the Legal Framework Impacting on Artistic Freedom of Expression is published by Vivarta. This publication is supported using public funding by the National Lottery through Arts Council England. It is licensed under Creative Commons CC BY 2.0, excepting where copyright is assigned elsewhere and marked accordingly.

ISBN: 978-0-9933345-2-8

Supported using public funding by Arts Council England

Vivarta is a digital media news lab and advocate for free expression rights. As vivarta.org we help defend free expression through investigative reporting and creative advocacy. As vivarta.com we apply new digital media, security and situational analysis tools to support this work. The Free Word Centre, 60 Farringdon Road, London EC1R 3GA www.vivarta.org

Five areas of law covered in this series of information packs

Child Protection

Counter Terrorism

Obscene Publications (available autumn 2015)

Public Order

Race and Religion (available autumn 2015)

They can all be downloaded from indexoncensorship.org/artandoffence

Editors’ note

As with the other documents in this series, this booklet is intended as an introduction to the legal framework that underpins the qualified right of freedom of expression enjoyed by artists and arts organisations in the UK. We hope that it will be of some assistance to artists, artistic directors, curators, venue management and trustees and others who seek to protect and promote artistic freedom of expression, especially when planning to programme challenging and controversial works.

This pack is not a substitute for legal advice.

If you are unsure about your responsibilities under the law at any time, you must obtain independent specialist legal advice. Some of the lawyers at work in the sector at time of publication are listed on the website.

Legal Adviser: Tamsin Allen, Bindmans LLP

Editorial team:

Julia Farrington – Associate arts producer, Index on Censorship/Vivarta

Jodie Ginsberg – Chief executive, Index on Censorship

Rohan Jayasekera – Vivarta[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”3″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1500536033776-87bf7048-0697-5″ taxonomies=”8886″][/vc_column][/vc_row]