Despite Standing Order 156 incidents of police harassment of journalists continues. (Photo: Jaxons / Shutterstock.com)

Raymond Joseph has joined Index as a columnist

Working as a reporter in the spiraling cauldron of violence in South Africa of 70s and 80s, I learned early on to be wary of the police, who would often harass, bully and even detain journalists for doing their job.

Often it happened when police, armed to the teeth, went into operational mode, firing teargas, baton rounds and even live ammunition to brutally break up protests.

While reporters were also targeted, it was photographers and cameramen who were really in the firing line. Toting cameras, they were easily visible. Their pictures or footage were regularly destroyed by police and their equipment damaged or confiscated.

As a young reporter, I became adept at stashing exposed rolls of film, slipped to me by photographer colleagues, down the front of my trousers to hide them from the police.

Anyone who worked as a journalist in those turbulent times has stories to tell of being pushed around and bullied by the police who saw the media, especially those working for the anti-apartheid era English language Press, as “the enemy”.

Fast forward two decades into post-apartheid South Africa and practically every working journalist also has a story of police harassment to tell, often arising from incidents when they were reporting or filming police officers. Many less serious incidents go unreported, accepted by journalists as part of the job.

This is happening despite the South African Police Service’s own Standing Order 156 that sets out how the police must behave towards the media. The language used is unequivocal and leaves no room for misunderstanding. It makes it clear that police cannot stop journalists from taking photos or filming, including photographing police officers. It also states that “under no circumstances” may media be “verbally or physically abused” and “under no circumstances whatsoever, may a member willfully damage the camera, film, recording or other equipment of a media representative.”

Yet despite high-level meetings between media and the police’s top brass, who say that such actions are not condoned, incidents continue to occur. The most recent meeting was in June this year between the South African National Editors’ Forum (SANEF) and the Johannesburg Metro Police after a photographer and TV cameraman were roughed up when they filmed officers arresting a drunk driver.

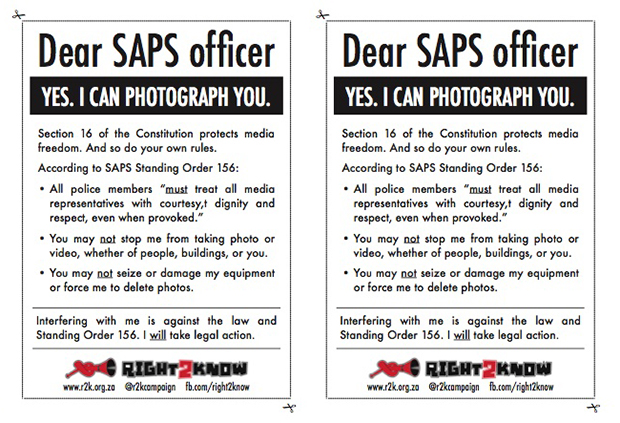

Incidents are happening so regularly that the Right2Know Campaign has published a booklet and cards explaining their rights for journalists to give to police if they are interfered with while on the job.

But, problematically, Standing Order 156 only deals with media and makes no mention of civilians who film the police using mobile phones.

“One shortcoming that we discovered in putting this together is that there isn’t enough protection for bystanders with cell phones,” says R2K spokesman Murray Hunter. “Under the Constitution, everyone has the same right to freedom of expression – working journalists and ordinary people alike. It’s especially important since bystanders with cell phones are often sources for mainstream media.

“But the direct orders that we refer to in this advisory only instruct police not to interfere with old-school media workers. So bystanders may still find themselves in a situation where the Constitution recognises their right to freedom of expression, but a police officer on the ground doesn’t.”

An example of the important role now played by citizens in newsgathering is the video footage shot by a bystander on a mobile phone of police brutalising taxi driver Mido Macia for an alleged minor parking offence. Sent anonymously to the Daily Sun newspaper, it led to the dismissal of nine policemen, who are now on trial for the killing of Macia.

One beacon of hope is that Standing Order 156 is under review after SANEF complained to the police about repeated media harassment. R2K sees this as an opportunity to include protection of the rights of citizen reporters, as well as media professionals, says Hunter.

But that could take time and involve protracted negotiations. And even if it happens there is no guarantee that police will heed the force’s own rules, or that the harassment of journalists and others will end.

It seems that the more things change, the more they will stay the same.

This column was posted on 6 August 2015 at indexoncensorship.org