This article is part of the summer 1995 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

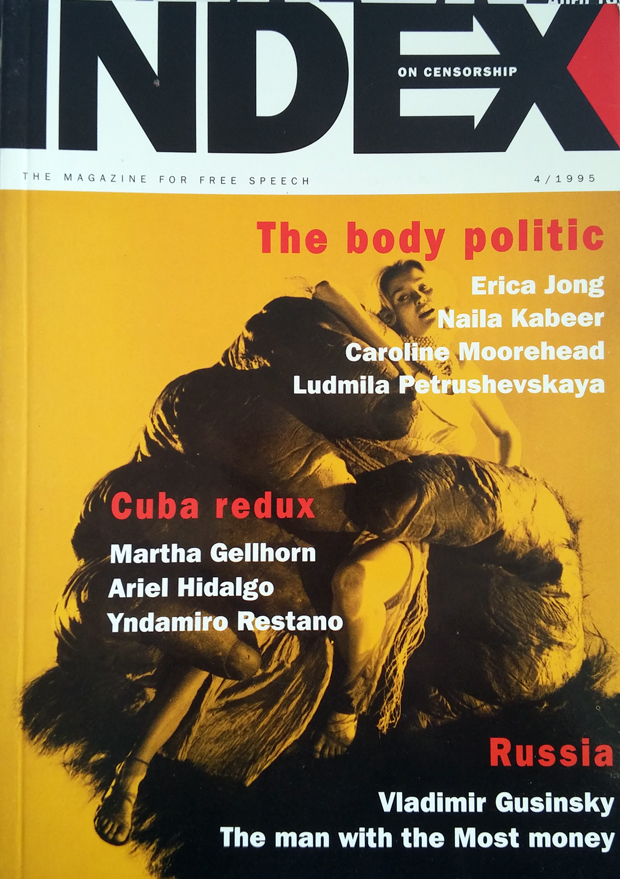

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by author Erica Jong, on pornographic material in art and literature, taken from our summer 1995 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend The body politic: censorship and the female body session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

Pornographic material has been present in the art and literature of every society in every historical period. What has changed from epoch to epoch – or even from one decade to another – is the ability of such material to flourish publicly and to be distributed legally.

After nearly 100 years of agitating for freedom to publish, we find that the enemies of freedom have multiplied, rather than diminished. They are Christians, Muslims, oppressive totalitarian regimes, even well- meaning social libertarians who happen to be feminists, teachers, school boards, librarians. This should not surprise us since, as Margaret Mead pointed out 40 years ago, the demand for state censorship is usually ‘a response to the presence within the society of heterogeneous groups of people with differing standards and aspirations.’ As our culture becomes more diverse, we can expect more calls for censorship rather than fewer.

Mark Twain’s notorious 1601 ... Conversation As It Was By The Social Fireside, In The Time of The Tudors fascinates me because it demonstrates Mark Twain’s passion for linguistic experiment and how allied it is with his compulsion toward ‘deliberate lewdness’.

The phrase ‘deliberate lewdness’ is Vladimir Nabokov’s. In a witty afterword to his ground-breaking 1955 novel Lolita, he links the urge to create pornography with ‘the verve of a fine poet in a wanton mood’ and regrets that ‘in modern times the term “pornography” connotes mediocrity, commercialism and certain strict rules of narration.’ In contemporary porn, Nabokov says, ‘action has to be limited to the copulation of cliches.’ Poetry is always out of the question . ‘Style, structure, imagery should never distract the reader from his tepid lust.’

In choosing to write from the point of view of ‘the Pepys of that day, the same being cup-bearer to Queen Elizabeth’ in 1601, Mark Twain was transporting himself to a world that existed before the invention of sexual hypocrisy. The Elizabethans were openly bawdy. They found bodily functions funny and sex arousing to the muse. Restoration wits and Augustan satirists had the same openness to bodily functions and the same respect for Eros. Only in the nineteenth century did prudery (and the threat of legal censure) begin to paralyse the author‘s hand. Shakespeare, Rochester and Pope were far more fettered politically than we are, but the fact was that they were not required to put condoms on their pens when the matter of sex arose. They were pleased to remind their readers of the essential messiness of the body. They followed a classical tradition that often expressed moral indignation through scatology, ‘Oh Celia, Celia, Celia shits,’ writes Swift, as if she were the first woman in history to do so. In his so-called ‘unprintable poems’, Swift is debunking the conventions of courtly love – as well as expressing his own deep misogyny – but he is doing so in a spirit that Catullus and juvenal would have recognised. The satirist lashes the world to bring the world to its senses. It does the dance of the satyrs around our follies.

Twain’s scatology serves this purpose as well, but it is also a warm-up for his creative process, a sort of pump-priming. Stuck in the prudish nineteenth century, Mark Twain craved the freedom of the ancients. In championing ‘deliberate lewdness’ in 1601, he bestowed the gift of freedom on himself.

Even more interesting is the fact that Mark Twain was writing 1601 during the very same summer (1876) that he was ‘tearing along on a new book’ – the first 16 chapters of a novel he then referred to as ‘Huck Finn’s autobiograph’. This conjunction is hardly coincidental. 1601 and Huckleberry Finn have a great deal in common besides linguistic experimentation. According to Justin Kaplan, ‘both were implicit rejections of the taboos and codes of polite society and both were experiments in using the vernacular as a literary medium.’

In order to find the true voice of a book, the author must be free to play without fear of reprisals. All writing blocks come from excessive self-judgement, the internalised voice of the critical parent telling the author’s imagination that it is a dirty little boy or girl. ‘Hah!’ says the author, ‘I will flaun t the voice of parental propriety and break free!’ This is why pornographic spirit is always related to unhampered creativity. Artists are fascinated with filth because we know that in it everything human is born. Human beings emerge between piss and shit and so do novels and poems. Only by letting go of the inhibition that makes us bow to social propriety can we delve into the depths of the unconscious. We assert our freedom with pornographic play. If we are lucky, we keep that freedom long enough to create a masterpiece like Huckleberry Finn.

But the two compulsions are more than just related; they are causally intertwined.

When Huckleberry Finn was published in 1885, Louisa May Alcott put her finger on exactly what mattered about the novel even as she condemned it: ‘If Mr Clemens cannot think of something better to tell our pure- minded lads and lasses, he had best stop writing for them.’ What Alcott didn’t know was that ‘our pure-minded lads and lasses’ aren’t. But Mark Twain knew. It is not at all surprising that during that summer of high scatological spirits Twain should also give birth to the irreverent voice of Huck. If Little Women fails to go as deep as Twain’s masterpiece, it is precisely because of Alcott’s concern with pure mindedness. Niceness is ever the enemy of art. If you worry about what the neighbours, critics, parents and supposedly pure-minded censors think, you will never create a work that defies the restrictions of the conscious mind and delves into the world o f dreams.

The artist needs pornography as a way into the unconscious and history proves that if this licence is not granted, it will be stolen. Mark Twain had 1601 privately printed. Picasso kept pornographic notebooks that were only exhibited after his death.

1601 is deliberately lewd. It delights in stinking up the air of propriety. It delights in describing great thundergusts of farts which make great stenches and pricks which are stiff until cunts ‘take ye stiffness out of them’. In the midst of all this ribaldry, the assembled company speaks of many things – poetry, theatre, art, politics. Twain knew that the muse flies on the wings of flatus, and he was having such a good time writing this Elizabethan pastiche that the humour shines through a hundred years and twenty later. I dare you to read 1601 without giggling and guffawing.

Erica Jong became internationally famous in 1973-4 with the publication of her novel Fear of Flying, which sold over 10 million copies worldwide. She has also written several collections of poetry and six further novels, most recently Any Woman’s Blues

Excerpted from a paper delivered at a conference on Expression, Offence and Censorship, organised by the Institute for Public Policy Research in June 1995. A full report of the conference, including contributions from Bernard Williams, Michael Grade, Clare Short MP and Chris Smith MP will be published shortly. Details from IPPR, 30-32 Southampton Street, London WC2E 7RA, UK

© Erica Jong and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the summer 1995 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.