The top of Frederike Geerdink’s blog, Kurdish Matters, still reads: ‘The only foreign journalist based in Diyarbakir’. The Dutch reporter was the only foreign journalist in Turkish Kurdistan until 9 September 2015 when she was deported from the country she lived and worked for nine years.

“There I went in a military convoy, first from Yüksekova to Hakkari, then from Hakkari to Van,” Geerdink wrote a few days later. “As the soldiers were playing loud, rousing nationalist music, I realised that I had turned into a PKK target, being transported on a dark mountainous Kurdistan road in a military vehicle with windows too small to see the starry sky.”

From Van, she’d fly to Istanbul where she’d be forced on a plane back to her The Netherlands. A couple of days earlier she had been arrested while traveling with and reporting on the activities of a group of Kurdish activists who call themselves the Human Shield Group. She was accused of illegally entering a restricted zone and engaging “in an act that helped a terrorist organisation”.

After nine years in Turkey, three of which were in Kurdistan, Geerdink had lost her second home. “I left my heart in Kurdistan,” she posted on Facebook after she’d landed at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport. “I don’t know when, but I will return.”

In the same week when Geerdink was deported, the English version of her book, The Boys are Dead, about the Roboski massacre and the Kurdish question in Turkey, was launched. “A coincidence,” she told Index on Censorship. “I don’t think the Turkish government had planned to help me promote my book.”

A few weeks after her ordeal, she was living a nomadic life in The Netherlands, moving from place to place, staying with friends or family, not really feeling at home anywhere. “I don’t want to be here,” she said. “Don’t get me wrong, everyone is really kind, but I don’t belong here anymore. I want to be there.”

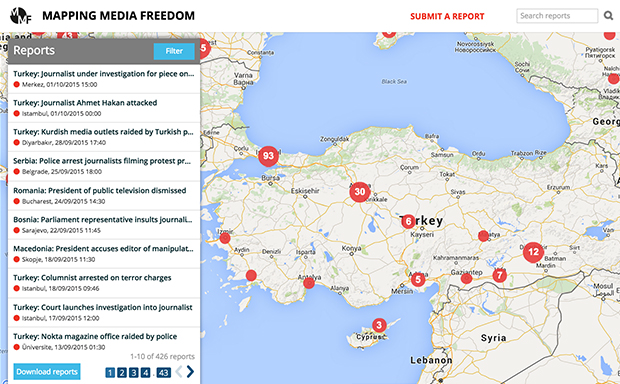

Turkey has one of the world’s worst records on media freedom. Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project has so far recorded 160 reports of violations against journalists in the country since May 2014. Reporters Without Borders has ranked Turkey 154th out of 180 countries on press freedom, and according to Freedom House, Turkey’s status declined from Partly Free to Not Free in 2013.

Reporting on the position of Kurds in Turkey is exceptionally difficult. Prominent journalists have been fired over their coverage of negotiations between the Turkish government and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Kurdish and Turkish journalists are often targeted by the police and courts, although it is rare for a foreign journalist to be singled out.

Back in January 2015, Geerdink was arrested by the Turkish authorities for the first time. Her house was searched, she was briefly detained and faced up to five years in prison for ‘terrorist propaganda’. Her detention was condemned worldwide and she was acquitted of the charges in April. Her deportation just a few months later came as a big shock.

Now that even foreign journalists are being targeted, Geerdink said, shows just how bad things are for the position of Kurds in Turkey. “I was the only journalist based there and now there’s one less witness on the ground. And the fewer the witnesses, the more the state has a free hand.”

She added that her treatment should be a warning to others. “They are saying: ‘watch where you go or we’ll kick you out’.” On the other hand, she thinks her deportation brings a lot of negative publicity onto the Turkish government and how they treat journalists, which can be used to put more pressure on the authorities.

In September, two UK-based reporters for VICE were arrested while reporting in Diyarbakir. Although they were released, their Iraqi colleague remains in jail. Seven local journalists are currently detained in the country, many of whom are Kurds. Being a foreigner, Geerdink said the spotlight is on her, but there are many Kurds in prison who nobody knows about, and they deserve the same amount of publicity. “For them it is a matter of life and death.”

Geerdink hopes to return to Turkish Kurdistan as soon as she’s allowed back in. Her lawyers are working hard to appeal the verdict on her deportation. Meanwhile, she is focussing on Syrian Kurdistan, Iraqi Kurdistan and Kurds in Europe.

“I will still be Kurdistan correspondent no matter where I am based.”

Mapping Media Freedom

|