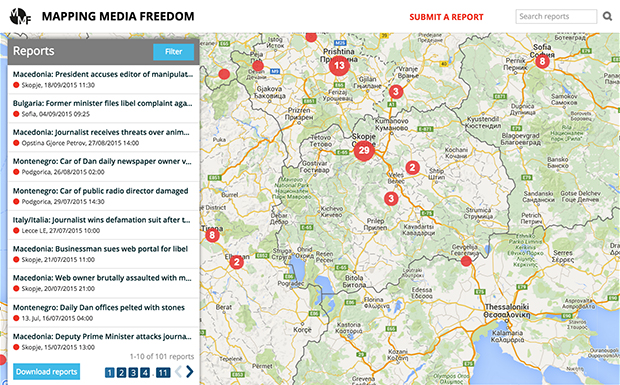

The successor nations to the former Yugoslavia are among the most difficult places for journalists to work in Europe, a fact borne out by the latest quarterly report from Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project. In the case of Macedonia there have been 35 verified incidents since the project began in May 2014.

Journalists have been subjected to verbal threats, online trolling, intimidation and physical assaults against their person and property. But another issue afflicting Macedonia’s 200 media outlets is more insidious: government advertising budgets of €30-40 million that warp the market and act as a constraint on media outlets and journalists alike.

“The outlets compete in a small, distorted market, covering around 2 million citizens, where they cannot survive financially unless they align their interests with the governing parties and politically-connected large businesses,” according to November 2014 report from the Association of Journalists of Macedonia (ZNM) report.

Since 2009, when the European Commission Progress Report first criticised the use of government advertising as a tool “to undermine editorial independence”, media freedom in Macedonia has become more openly discussed.

According to a report published by the government, between 2012 and the end of the first quarter of 2014, ruling parties spent about €18 million on 27 government media campaigns. It spent €6.6 million in 2012, €7.2 million in 2013 and almost €4 million in the first six months of 2014. To date, the report was the only time that the government released information about public money spent on promotional or awareness-raising advertisements.

Most government-funded advertisements are aimed at informing citizens about the benefits of reforms, encouraging innovation and entrepreneurialism and promoting family values. In a statement on state ads, ZNM said: “Government campaigns have nothing to do with the public interest and are pure political propaganda of the government paid by public funds.”

“The government claims that campaigns are implemented in order to inform citizens about the importance and significance of specific policies and measures,” ZNM wrote. In effect, the organisation said, Macedonia’s government uses taxpayer money to tell citizens that its efforts have been successful, whether or not the reforms have actually succeeded.

After criticism from Brussels, the Macedonian government temporarily halted state-funded campaigns, and, as Balkan Insight reported, this will last “until the authorities agree on tighter rules for spending public funds on ads”. Unpaid public service announcements were not affected by the order.

The 2014 annual report examining the broadcast market from the Macedonian Agency for Audio and Audiovisual Media Services did not include a breakdown on government advertising spending, a departure from previous years. The 2012 report showed that the government had been the largest single source of ad budgets, outpacing telecommunication firms, Proctor & Gamble and Coca Cola. The government slipped to become the second largest advertiser, according to the .

A study conducted by ZNM examined the €18 million spent on advertising by the government since 2012. According to the report, the largest slice of the advertising buys were directed to pro-government media outlets “creating even more robust political-clientelistic and corrupt links between the government and the media”.

Another organisation, Media Integrity Matters, found that the government’s role in the advertising marketplace was deleterious. “These phenomena have prevented the media from performing their basic democratic role – to serve the public interest and citizens” the organisation wrote in its report, which recommended that media finances be transparent and monitored by independent bodies.

Mapping Media Freedom

|