The return of Vladimir Putin as president of the Russian Federation in 2012, after a wave of protests, was followed by the implementation of a new law that required non-governmental organisations receiving foreign support — in the form of funding or material aid — and engaged in “political activity” to register as “foreign agents” with the Ministry of Justice.

There are currently eight organisations advocating for media freedom and journalists’ rights included on a black list of 86 NGOs. Among them are organisations fighting for access to information (Freedom of Information Foundation), providing legal support to journalists (Rights of the Media Defence Centre and Media Support Foundation (Sreda)), organising education for regional reporters (Press Development Institute – Sibir in Novosibirsk and Regional Press Institute), an information agency (Memo.ru) and others.

Foreign agents have additional responsibilities and duties, including having to report twice as often and providing more information to the Ministry of Justice than other NGOs. A notice reading “Published by an NGO – foreign agent” must mark everything they publish, although some refuse to comply. In the Russian language, “foreign agent” has strong negative connotations associated with Joseph Stalin’s Soviet-era political repression. Some would say the term implies that NGOs are spies or traitors.

Only one organisation in Russia had voluntarily identified itself as a foreign agent before July 2014 when new rules allowed the Ministry of Justice to put NGOs on the list as it sees fit.

Some of the media freedom organisations are in the process of shutting down, including Sreda and Freedom of Information Foundation, while others, such as the Regional Press Institute (RPI) in St Petersburg, continue their activities but are forced to pay large fines.

Anna Sharogradskaya, the director of RPI, says she would never register the NGO voluntarily. “Article 51 of the Russian constitution says that nobody is obliged to give incriminating evidence against himself or herself and labeling the RPI would be not only incriminating evidence, it would be slander on our donors,” Sharogradskaya says. “So why should I break the law?”

Since 1993, RPI has provided seminars for journalists from Russia’s northwest region, offered its facilities as a venue for independent press conferences and meetings, and organised discussions on topical issues.

The organisation has come under increasing state pressure. In June 2014, customs officers at the Pulkovo International Airport in St Petersburg detained Sharogradskaya and searched her luggage. She missed her flight to the USA where she had been visiting scholar at Indiana University. Her notebook, memory stick and other gadgets were confiscated without explanation. For more than 10 months, Sharogradskaya was suspected of terrorism and extremism, after which she was cleared of all charges and her belongings were returned — although not in working order.

In November 2014, Putin promised that the St Petersburg regional Ombudsman Alexander Shishlov would look into the RPI case. “And he did: some days after this meeting, the Ministry of Justice put my organisation on the list of foreign agents,” says Sharogradskaya.

A court in St Petersburg fined RPI 400,000 rubles ($6,150) for refusing of add itself to the list voluntary. Half of the amount was paid by Russian and international journalists around the world, and the rest was added from Sharogradskaya’s personal savings.

Despite the pressure, RPI continues acting as an independent help desk for journalists, giving the region’s media, bloggers, initiative groups, democratic opposition leaders, and activists an opportunity to raise their voice at press conferences, and advocating for those who are in trouble with the authorities.

Many, including Sharogradskaya, believe that Russian civil society, including the media, faces increasing pressure. NGOs advocating for the freedom of the press must now spend more time and efforts protecting themselves instead of protecting journalists and other parts of the media.

Sharogradskaya says that above everything else, the lack of solidarity among journalists is a major concern. “Our work is to raise this solidarity. This is the only way to withstand the time of repressions.”

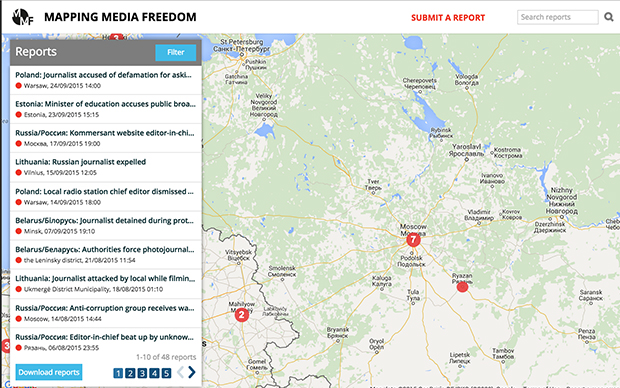

Mapping Media Freedom

|