When the Tomsk-based station TV-2 ceased broadcasting earlier this year, Siberia lost one of its few independent stations. The channel was about as free as media can be in Russia: it wasn’t funded by a state or municipal budget.

The road to its closure began in April 2014 when an antenna malfunctioned. It took 45 days to get back on the air. When it resumed transmission in June 2014, Roskomnadzor – the Russian authority that oversees media and communications – revoked the station’s right to broadcast. A previous licence extension though 2025 had been issued as a result of a “computer error”, the agency explained.

On 1 January 2015, the station stopped broadcasting over the airwaves. In February 2015, it ceased to be an internet and cable station as well.

In Russia, independent media will not likely be shuttered because of critical coverage of the state. It will have its licence revoked because glitch or be silenced through a broken feeder or some other mundane technicality.

Early in the Putin era, Moscow-based national networks could be caught in a “dispute of economic entities” to silence narratives that were contrary to the government’s line. Media takeovers by businesses aligned with the government of President Vladimir Putin drew the world’s attention and criticism. But in Russia’s hinterland, the decline of media freedom was more precipitous.

Despite a professed respect for the rule of law in Russia, regional media outlets are caught between harsh oversight by local authorities and a lack of independent sources of funding. At the same time, business interests and regional governments are often more closely affiliated than in larger cities. Nepotism and conflicts of interest are rife while courts are hamstrung by corruption.

Journalists are often victims. According to Glasnost Defense Foundation, 150 journalists were killed in Russia during last 15 years. Authorities ignored crimes against journalists and tightened the screws by criminalising slander, which spurred lawsuits that helped destroy independent-minded free media.

When journalists do uncover corruption, regional authorities act to silence them by meting out punishment for “crimes” that the individual has committed. This is highlighted by the recent case of Natalya Balyakina, editor-in-chief of the newspaper Chaikovskie Vedomosti. A well-known journalist who investigated allegations of misconduct by local officials involving the area’s municipal housing and human rights violations, Balyakina was awarded the 2007 Andrey Sakharov prize for journalism.

On 22 October 2015, the Chaikovski city court sentenced her to three years of incarceration and 761,000 rubles ($11,818) in fines and damages. Balyakina was convicted of a crime that she allegedly committed five years ago, when she was director of the regional City Managing Company. Her former company has accused her of misappropriation and embezzlement.

Whether or not the allegations against Balyakina are true, Chaikovski regional authorities benefit by having yet another investigative journalist silenced.

Regional media must also contend with a dearth of independent funding. As a result, these outlets are often forced to sign affiliation agreements with local administrators. These deals come with restrictions on how the organisations can cover regional government activities.

Journalists reporting for these affiliated outlets say they receive direct instructions on what they can write about. The editor-in-chief of one newspaper was prohibited from publishing any issues regarding healthcare because there was nothing positive to cover. Regional events that are reported by national media — disasters or human rights violations — are not covered by local outlets due to positive news restrictions.

But even the cowed national media is under continued assault. The Russian Duma is considering a bill that will allow Roskomnadzor to compel media organisations to disclose foreign funding or material support. So software provided by Microsoft could cause a regional outlet to be labelled as a “foreign agent” on the same model of the NGO law that was passed in 2012.

Long under pressure from official censorship and self-censorship, journalists’ sources are now being constrained by punitive laws that have enlarged state secrets and toughened punishments. In June 2015, Putin signed a law that classified Ministry of Defence casualties during peacetime. The result is that journalists are now forbidden from reporting on the number of Russian soldiers killed in action in Ukraine or Syria.

The Federal Security Service (FSB) is also lobbying members of the Duma to pass a draft law that restricts freedom of information around real estate transactions. Some observers say that this will hinder work to uncover corruption committed by Russian officials carried out by bloggers and journalists.

The media in Russia became one of the core targets during the strengthening political powers in last decades, but the regional journalists are put in an especially weak position.

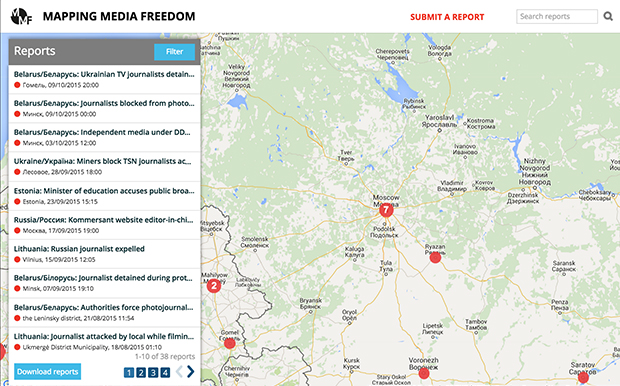

Mapping Media Freedom

|

This article was posted at indexoncensorship.org on 13 November 2015