If you want to understand the media environment in Macedonia, the phenomenon of parallel journalists’ organisations is a good place to start. Initially, the associations were created to promote and protect professional standards and freedom of expression. However, in the hands of politicians and elites, the groups have become a tool for creating parallel realities.

The Association of Journalists of Macedonia (ZNM) and the Macedonian Association of Journalists (MAN) have similar missions. ZNM was founded in 1946 as “an independent, non-governmental and non-political party organization whose purpose is to be the protector and promoter of professional standards and freedom of expression”. MAN was formed in 2002. Both have impressive codes of conduct, mission and vision statements and stress strengthening unity within the profession.

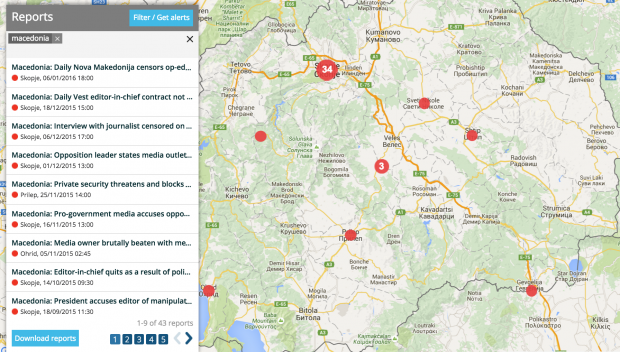

In practice, however, because Macedonia is a polarised society most journalists are aligned with the governing party or its opposition. There are very few truly independent reporters. This is a trend that has been borne out by the latest verified incidents reported to Mapping Media Freedom.

Take, for example, two incidents that tool place on 14and 15July 2015. In both reports, the victim was Sashe Ivanovski, a highly controversial citizen journalist and owner of the web portal, Maktel. He is a vocal critic of the government and quite often uses unusual means to pose questions or demonstrate his critiques. On 14 July — in front of dozen witnesses — Ivanovski was physically assaulted by Aleksandar Spasovski, a reporter for TV Sitel, a pro-government broadcaster. Some local media outlets report that Ivanovski, during Spasovski’s live reporting, yelled something that was eventually aired live on TV. Spasovski approached Ivanovski and whispered in his ear, “I will kill you” before slapping him twice. Other TV crews caught the incident on camera.

In the 15 July incident, Vladimir Peshevski, deputy prime minister for economic affairs, also physically assaulted Ivanovski. While recording with his mobile phone, Ivanovski approached Peshevski, asking him about the wiretapping scandal in Macedonia. Peshevski then turned to attack Ivanovski in front of the clientele of a cafe bar. This incident was also recorded.

ZNMstrongly condemned the assaults on Ivanovski, while MAN— of which Spasovski is a member — condemned Ivanovski’s behavior, stating that he is “not a journalist” and that he “was obstructing the work of Spasovski”. Based on these two diametrically opposed statements, the media set about creating two opposing narratives.

At first, information was aired only on independent media — which is significantly smaller than pro-government media — and those outlets that are close to the opposition. In this narrative, the attacks on Ivanovski were deplorable. The second narrative was that of the pro-government media, in which Ivanovski was actually accused of obstructing another journalist’s work. It was also claimed that Ivanovski himself is not a journalist, therefore the attack from Peshevski had no bearing on freedom of expression.

In a written reaction, Kurir, a pro-government media outlet, accused the country’s biggest opposition party of undermining media freedom. It wrote that SDSM, the main opposition party in the country, regularly puts pressure on them during their press conferences by accusing them of not being professional journalists. Only MAN condemned the incident while there was no reaction from ZNM.

So far, there is only one case that has been condemned by the both organisations. That was when the opposition leader Zoran Zaev said that he considers the national broadcasters — Sitel, Kanal 5, Alfa and MRTV, and also the daily Dnevnik — as “his greatest political enemies”.

Reading the statements published on the web pages of ZNMand MAN is like reading the media situation in two different countries. MAN’s statements create the impression that the opposition in Macedonia rules the country and uses its enormous resources to control the media. Similar claims are made by the governing parties in neighboring countries with autocratic tendencies. Then there is ZNM, where most incidents are recorded, but some are missing, especially when pro-government journalists are targeted by the opposition parties and supporters.

The trend of politically-aligned journalists’ organisations is not exclusive to Macedonia. In Croatia, for example, a second journalists’ association was created and supports the interests of the new centre-right government. The goal of politicians in many countries seems to be to make the media less effective by driving a wedge between journalists.

Mapping Media Freedom

|