Referred to as Shashibiya or Old Man Sha, Shakespeare’s star is shining bright this year in China. On top of a UK government-funded initiative to translate his complete works into Mandarin, the Royal Shakespeare Company has embarked on its first major tour of China. Called King and Country, the tour includes performances of Henry IV Part I, Henry IV Part II and Henry V in Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong.

None of this would have been possible 40 years ago, when China was still under the dark shadow of the Cultural Revolution, between 1966 and 1976. Shakespeare was banned, alongside a series of other Western playwrights, his work was labelled bourgeois and lumped into the doomed category of moral and spiritual pollution. When the government finally lifted their ban on Shakespeare in 1977, it was seen as a sign of political liberalisation. Indeed his coming back into favour was evidence that the Cultural Revolution really was over and that China had moved on.

But Shakespeare’s re-emergence was still political, albeit of a different political nature. After the death of communist leader Mao Zedong in the late 1970s, a new ideology was being propagated. This ideology supported a market economy under the banner of socialism with Chinese characteristics. Shakespeare could easily adapt to this new look – and his plays quickly did. Enter the era of the big and brash Shakespeare shows, which continue today. State productions are typically extravagant and driven by a message: China is modern, culturally plural and open to the West.

Chinese-British actor Daniel York was part of one of these big productions. He acted in a 2006 bilingual version of King Lear in Shanghai, the bare bones of which he outlined to Index. It was set in a future Shanghai, which is a leading international centre with a bilingual population, where King Lear was played by a Hong Kong billionaire businessman. The play climaxed with a battle, as in the original, only the location had shifted away from the jagged cliffs of Dover to the heat of the Chinese stock exchange.

Whatever the political mood, the Chinese government uses Shakespeare to reflect it. It’s made easy by how Shakespeare is taught in China, namely in the Chinese department as part of world literature, and the drama department, but not in the English department. Tuition is in Mandarin and so the pupil is directly at the mercy of the teacher.

As scholar Murray Levith writes of Shakespeare: “Perhaps more than any other nation, China has used a great artist to forward its own ideology rather than meet him on his own ground.”

The Chinese Communist Party does not have a monopoly on Shakespeare and what ideologies are advanced through his plays. Other Chinese voices have come to the fore, some of which are overtly critical of the government. A case in point is the film, Prince of the Himalayas. This 2009 movie, based on Hamlet, was an instant hit, airing at cinemas across the country and even spawning stage recreations. The film – shot in Tibet – was about a prince who returns to his kingdom to find he has been usurped. The allegory of modern Tibet was not lost on many movie goers. Yet it was set in a pre-modern mythical kingdom and it was Shakespeare, so it was allowed. In some instances Shakespeare can extend the limits of free speech.

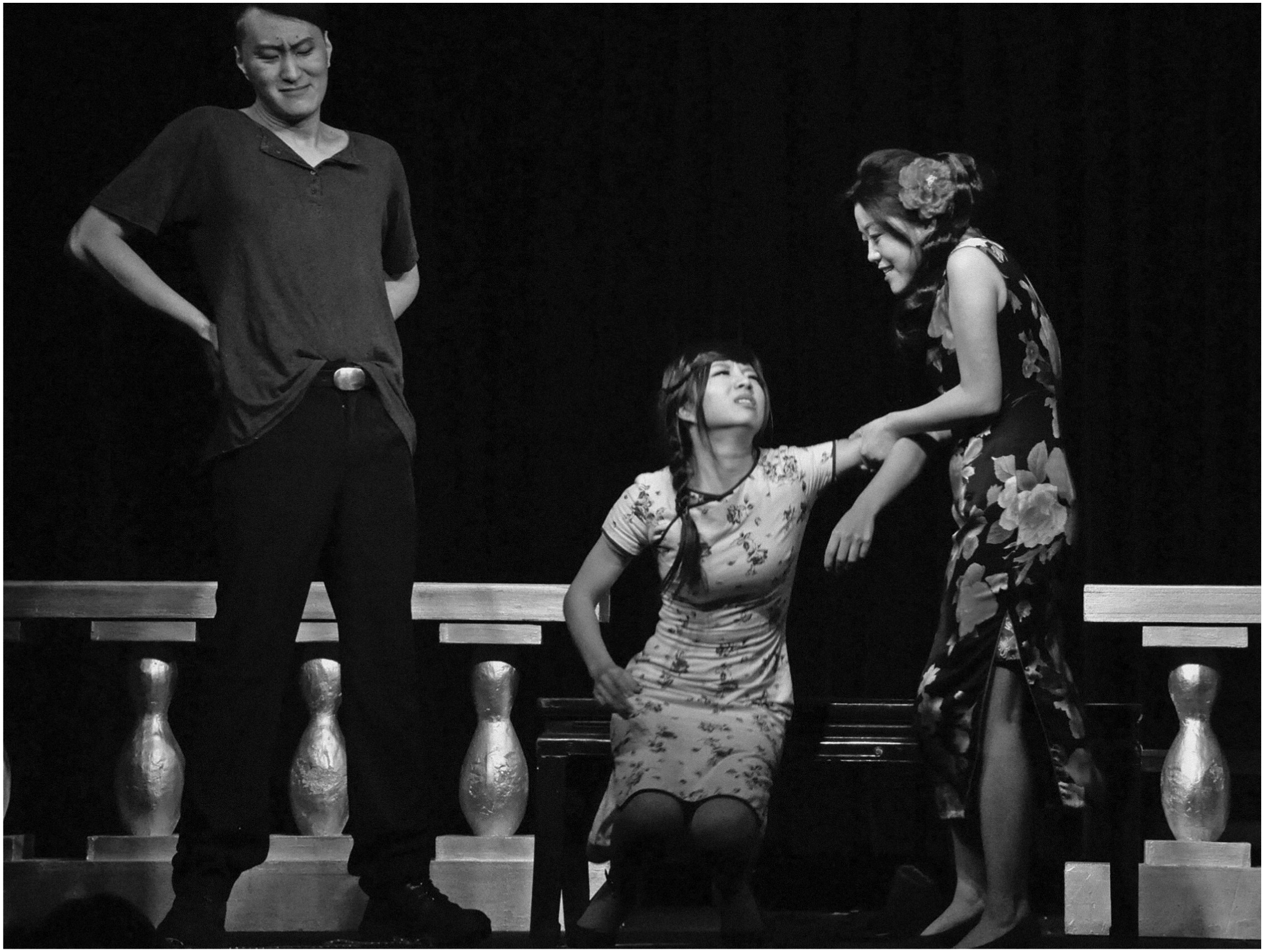

Other interpretations are less political and yet still use Shakespeare as a means of furthering their own agenda. Alexa Huang, an expert on Shakespeare in China, told Index about watching The Taming of the Shrew in Beijing back in 2006.

“They took the taming literally, disciplining Katherine for her behaviour,” said Huang, who is a professor at George Washington University. She’s also seen productions of King Lear, which have been interpreted in China as an allegory for fulfilling filial duty. Unlike the typically sympathetic portrayal of Cordelia, in China she is seen as stepping out of line, a defiant character who publically shames her father. Placed within the context of a country which has a long way to go in terms of female liberation and still values Confucianism, the message behind both of these examples is clear.

“With Shakespeare you almost have a total free licence,” said Huang. That certainly might be the case. China’s current president, Xi Jinping, is a huge fan of Shakespeare. He even went out of his way to seek banned copies of the plays during the Cultural Revolution.

Alison Friedman from Ping Pong Productions, a company that seeks to bring China and the world closer through the arts, has a similar view. She helped stage a US version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 2014. Friedman said she has had no problemsproducing her work in China.

“Generally speaking (and it certainly changes when the pendulum swings, which it does), we find if you don’t bother them they don’t bother you.”

She added: “When it comes to the performing arts, China is a much more open space than the outside world thinks it is. What a lot of young and independent artists face is lack of funding rather than political persecution.”

Naturally part of the success of more controversial Shakespeare interpretations lies in the main arena being the stage. The CCP does not approach theatre in quite the way they do other more mainstream media.

“Playwrights joke that censors only pay attention to films and TV. They [the censors] are busy. They don’t read between the lines and they’re not literary critics,” said Huang.

This does not mean that anything goes. Huang highlights another play, based on Hamlet, which has yet to see the light of day. Called Tomorrow We Are Carrying The Coffin To The Cemetery, it was written by a young playwright straight after the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989. He never allowed it to be performed because of fear of death threats.

And back to the futuristic Shanghai of King Lear, York believes self-censorship came into play. “It steered clear of politics, corruption and triads,” he said.

Shakespeare’s introduction into China can be traced back to British colonial efforts in the 19th century, and a translation of Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales From Shakespeare (1807), was published in 1903 and 1904, with the first complete translation of a Shakespeare play appearing in 1921 when Hamlet was published.

Performances of Shakespeare’s plays did not gain their audiences in China just against a backdrop of the political. Rather, they were always central to the political scene. They grew in popularity in line with a new form of theatre. Huaja, known as spoken drama, was more confrontational in nature. It was in direct contrast to xiqu, Chinese opera, which dominated the stage until the early 20th century. China’s young revolutionaries and reformers viewed xiqu as decorative. Huaja, by contrast, could serve a political or educational purpose.

An early 20th-century performance of The Merchant of Venice exemplifies this. Influenced by ideas of female liberation coming out of the new women’s movements, students at Shanghai’s St John’s University staged the play with the character of Portia given a very positive portrayal.

As the political mood shifted in China in the middle of the century, so too did the interpretation of Shakespeare. Under the early communists, the bulk of literature in translation came from the Soviet Union, having been reworked to reflect Marxist-Leninist values. King Lear was described as “a portrayal of the shaken economic foundations of feudal society”; Romeo and Juliet was about “the desire of the bourgeoisie to shake off the yoke of the feudal code of ethics”. Then there was Hamlet, the most translated of Shakespeare’s plays and the most in line with the CCP. Bian Zhilin’s 50,000-word essay on Hamlet from 1957 set the tone. Bian depicts Hamlet as someone who aligns himself with society’s underdogs.

“Through his bitter thinking (ie his soliloquies) and his mad words, Hamlet realises the social inequality and the suffering that the masses have borne. Such an experience not only makes Hamlet hate his enemies more but also gives him more strength to carry on his fight.”

“This was Shakespeare with Chinese socialist characteristics,” said Huang. “The belief was that Shakespeare spoke for the proletariat.”

China might have largely moved on from thinking Shakespeare speaks for the proletariat, or even that Shakespeare is Western spiritual pollution, but utilising Shakespeare for a political or social cause continues. Time will tell how he will be used in the future.