Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

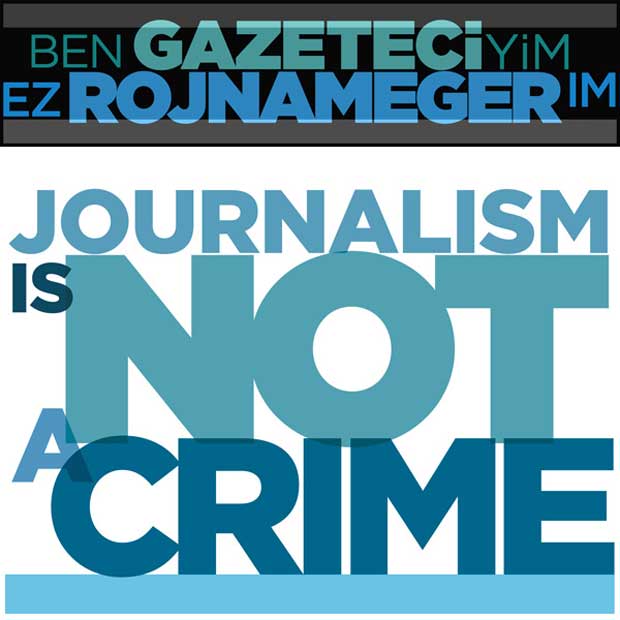

44 journalists are in Turkey’s jails tonight. We demand their release. Because we, too, are journalists, and… pic.twitter.com/jzDsd9MOqm

— P24 (@P24Punto24) July 11, 2016

The above was part of a series of tweets were sent out by Platform for Independent Journalism (P24) near midnight on 11 July. P24 joined editors, reporters, columnists, bloggers and civil society activists, who are, despite being a minority in the shackled media sector in Turkey, determined to defend the honour of our noble profession till the very end.

The “Journalism is not a crime” logo is now in circulation in Turkish, Kurdish, English and a variety of other languages. The hope is that this slogan will trigger widespread domestic and international solidarity to rescue Turkey’s journalism from being turned into a total wreck.

On Tuesday morning, I watched three of the figures behind the campaign on TV. It is a rarity, these days, that any voice in defence of freedoms and rights find a public space on Turkey’s TV stations. It filled me with a sense of pride, hope and courage, but was tinged with a slight sense of despair.

That any so-called private mainstream TV channel would invite them on to share their views is a daredevil act, because these newsrooms are practically run by the same proprietors and their puppet editors, whose variety of businesses are strictly dependent on the public contracts, and any challenge to the AKP government would mean severe punishment. This is the impact self-censorship, in addition to direct censorship, has had on public debate as well as free reporting in roughly 90% of the Turkish media.

The appearance of Fehim Işık, a Kurdish columnist, Said Sefa, owner of the independent news site Haberdar, and Arzu Demir, a leading figure in the Turkish Journalists’ Union on the tiny Can Erzincan TV took place with an air of gloom. One of the three or four channels still willing to broadcast critical and diverse content, this channel will be dropped fromTurksat satellite by 20 July, on the back of a murky decision by the satellite board over claims it spreads terrorist propaganda.

Experienced lawyers are flabbergasted once more by the lawlessness reigning over the media domain, but there is little they can do about it. A month or so ago, another TV channel, IMC TV, met the same fate and was forced to switch to a different satellite service, losing more than 75% of its mainly Kurdish audience. Can Erzincan TV, a financially strapped and tiny liberal outlet, will also lose viewers. This is a cunning form of censorship by the authorities.

With Can Erzincan TV pushed out of the limelight, Turkish viewers will be left only with Halk TV and FoxTV, both of which are also in the crosshairs for further punitive actions.

When – rather than if – they also are gone, the AKP will have a free ride on the most powerful, efficient medium in journalism. Remnant portions of dignified journalists, regardless of their political colour, will have to retreat into a handful newspapers and news sites.

This is the bad news.

The good news is that, as I expected, the very core of real journalism in Turkey is intent on professional resistance to further erosion. The current initiative #Iamajournalist is yet another amazing attempt to rise up. I watched it develop spontaneously as a social media movement, which rapidly turned into a community action.

The very good news is that it now contains elements which find common cause between the liberals, leftists, Kurds, seculars, and concerned conservatives: protecting journalism as the main pillar of democracy. This is unfinished business in Turkey, and something the country’s “dark forces” want to reverse in full.

For a week starting from July 11, a handful of newspapers, websites and TV channels will display the “Journalism is not a crime” logo. Social media, too, is busy.

“Protecting freedom of press also means defending the public’s right of access to information. In a society where the right to information is restricted, one cannot speak of democracy,” they say.

“As journalists we will do everything within our power to be the voice of those who have been marginalised, imprisoned, and silenced for doing their jobs and defending the freedom of press and freedom of access to information for all of us.”

We must now keep in our minds the 44 journalists in Turkish jails. It’s a grim number that will rise. There are thousands of journalists who are forced to operate in newsrooms resembling labor camps, or — to use a term I used in my Harvard paper a year and a half ago – “open-air prisons”, subordinated to spread propaganda, lies and hate speech.

This spontaneous initiative, which grew without the involvement of some polarised journalist organisations, needs attention, and support. Journalists in Turkey are tough nuts, but the conditions are swiftly hardening. We need to keep the spirit of journalism alive.

Diana Reyes Rafael is a member of the What a Liberty! project.

On 6 July, the What a Liberty! team made its voice heard publicly for the first time with the official launch of Magna Carta 2.0 in Lincoln. We put ourselves in front of ordinary people in order to inspire and engage.

We found the strength and encouragement to stand up and tell society what we have to say. Although many of us may not be old enough to vote, we are not going to stand by while democracy – a principle our ancestors fought for – is taken away.

Why did we choose Lincoln? Because Lincoln is the spiritual home of this project. We first went there to learn about the Magna Carta, its importance and its impact. We must look at the past so we can understand the present and Lincoln is the place where our inspiration lies. It is the link between the Magna Carta and our Magna Carta 2.0. In 2016, however, it was us taking the lead.

During our first presentation, we were quite calm because it was an informal chat with 11-year-old school children. What fascinated me most was hearing their concerns and the actions they wanted to take to achieve their goal. For instance, they want a mixed football team of boys and girls at their school and new tactics to combat bullying. That made us realise that even younger children have something to say.

During our second presentation we spoke to people of all ages and helped them realise that although young people are portrayed in society as ignorant, there are many passionate voices among us who want to make a change.

Overall, the day was awe-inspiring. We learned that all it takes to stand up and speak in front of people is passion. When I gave my presentation I did not have a prepared speech because I wanted to be spontaneous and sincere. I also wanted to inspire because What A Liberty! is all about the incentive you need to create change. What did I receive in exchange? A round of applause and words of recognition.

To any young people looking to have their voices heard, I would say: “Anyone can be good at it, you just have to believe in yourself and find what you are passionate about.”

At the end of the day, we are all humans and sometimes we may think there is nothing to aim for. But when we take the time to look around we often find someone or something to inspires us.

What a Liberty! brings together 18 young people from all across London.

The members are:

When you hear the words “hip hop”, you may think about girls, guns and the other usual stereotypes that haunt the genre. Your mind is much less likely to wander to the dusty tomes of academia. Yet if the Power of Hip Hop proved anything, it’s that through a unique mix of academic presentations and live performances, hip hop’s capacity for facilitating social change across the world is undeniable.

The two-day event, co-organised by Index on Censorship and In Place of War, began with a day of academic presentations that proved hip hop is as worthy an avenue of study as any other musical genre. A new paper by Veronica Mason, a lecturer at London Metropolitan University who spoke at the event, will be the first inter-generational study of hip hop in academia, and having a platform to share that with other hip-hop academics is invaluable.

Then came a day of performances from the likes of Zambezi News, two satirists and hip hop artists from Zimbabwe who had the whole venue laughing over their impression of Mugabe, and Shhorai, a Colombian MC and microbiology researcher. Shhorai rhapsodised about being in the UK, telling Index how willing Londoners are “to give you a hand, to smile, to help you”. In fact, this solidarity that In Place of War has helped to cultivate over the past decade seems to have generated a real sense of female solidarity in Shorrai: “We need to support each other because it’s the only way that we’re going to move forward.”

When asked what the Colombian touch in hip hop was, her answer was immediate: “The best exponents of Colombian hip hop are great freestylers. But there are very few women because the battles are sexist. The guys just say ‘it’s a gathering of witches, nothing more.’”

But no one had anything negative to say in RichMix when she performed along with Poetic Pilgrimage, a frank, Muslim female duo. In fact, the audience went on to happily digest what was an appropriately heavy second day of the event when figures like Afrikan Boy and Rodney P freestyled about the recent shootings in the US. Having talked about how “music is my visa”, the gang-ridden streets of Afrikan Boy’s youth seemed closer than ever as he talked about seeing Alton Sterling’s bereaved son break down at the press conference. “I had to just sit down and cry those tears. It struck me as a father. I thought – my life’s going to get taken away for that?”

“No justice, no peace, persecute the police,” was the thoughtful, provocative refrain of his rap that held the audience in the palm of his hand.

A genre that began with a party Bronx in the 1970s has, without a doubt, gone on to transform lives across the world. Whether you grew up in Colombia or London, Zimbabwe or Bristol, it is a genre that enriches the impoverished, educates the deprived and represents the unrepresented. After such an empowering weekend, all that’s left to wish for is that their voices will be heard.

“We’re Zimbabwe’s leading satirical show. We’re also Zimbabwe’s only satirical show” Zambezi News on fleek ✌?️? pic.twitter.com/QbXu8u2U4v

— Sophia Smith Galer (@sophiasgaler) July 8, 2016

Clip of @SHHORAI rapping at #PowerOfHipHop @RichMixLondon @IndexCensorship @inplaceofwar #conocimiento #callejero ? pic.twitter.com/MH8fDzZio2

— Sophia Smith Galer (@sophiasgaler) July 8, 2016

More from the Power of Hip Hop:

– Poetic Pilgrimage: Hip hop has the capacity to “galvanise the masses”

– Colombian rapper Shhorai: “Can you imagine a society in which women have no voice?”

– Zambezi News: Satire leaves “a lot of ruffled feathers in its wake”

– Jason Nichols: Debunking “old tropes” through hip hop

Index on Censorship supports the “I am a journalist” campaign launched by journalists and media freedom advocates from Turkey.

We stand in solidarity with our colleagues in Turkey who fiercely continue their jobs despite facing relentless attacks and attempts to silence them. We also express our support to the 44 journalists and news distributors in jail, and to those facing arrest as retaliation for exercising their right to freedom of expression and freedom to inform.

Here is the campaign statement:

Journalism is not a crime.

In Turkey, harassment of the press is getting worse by the day.

Those who are struggling to protect media freedom and do their jobs are forced to pay a heavy price.

Journalists reporting from conflict zones are subjected to constant threats, putting their lives in danger.

Reporters, editors and writers often face criminal investigations, and can be prosecuted for defamation. Many of them are held in custody awaiting trial or are imprisoned because of their reports or posts on social media.

Journalists are easily labeled as enemies of the state, traitors or spies, and are prosecuted on such charges as “spreading propaganda of terrorist organisations”.

Foreign journalists who live and report from Turkey have not been immune to these allegations. Journalism has come under attack during different periods of Turkish history but members of the international press have never been targeted on this scale.

Journalists in the mainstream media are forced to work in such conditions that they cannot do their jobs properly anymore, and can be easily fired if they question the official government line. Heavy censorship is the norm and critical voices are constantly stigmatised.

The facts are restricted by frequent media blackouts. Those the challenge the blackouts are usually labelled as traitors, or even as terrorists, and presented as criminals. Various independent media outlets are under permanent threat of being shut down.

People from different sectors of society who show solidarity with journalists to defend press freedom, as well as the right to information, have also become targets of investigation and prosecution.

However, these pressures have not stopped a group of journalists from traveling to Diyarbakır from the western cities of Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir this year to show solidarity with their colleagues who work under immense pressure in conflict zones. They stand together in front of prisons, the courthouses and at news desks.

Protecting freedom of press also means defending the public’s right of access to information.

In a society where the right to information is restricted, one cannot speak of democracy.

Therefore, as journalists we will do everything within our power to be the voice of those who have been marginalised, imprisoned, and silenced for doing their jobs and defending the freedom of press and freedom of access to information for all.

As journalists from Turkey, we cry out once again:

Journalism is not a crime!