Following last month’s failed coup, journalists in Turkey are facing the largest clampdown in its modern history. Journalists covering the events from abroad have not escaped unscathed, including a number in the Netherlands who have faced threats and attacks.

Unusually, the journalists of the Rotterdam-based Turkish newspaper Zaman Today welcomed the increased police presence. Long before the military coup that failed to remove Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan from power, the government had been targeting journalists. But today a Dutch police officer drops by frequently to check if Zaman’s journalists are alright. It makes journalist Huseyin Atasever, who has been working for the Dutch Zaman since 2014, feel safe. Or at least safer than he has felt in a while.

On the morning of Tuesday 19 July Atasever was on his way to Amsterdam when he received a phone call. A Turkish-Dutch individual had been abused by Erdogan supporters at a mosque in the city of Haarlem. Atasever decided to go there immediately.

“I found a man sitting in a corner on the floor talking to the police,” he told Index on Censorship. “He was injured and his clothes were torn.”

After Atesaver had interviewed the victim, who had been targeted for being critical of Erdogan, he approached a group of Erdogan supporters nearby to hear their side of the story.

“When these men realised that I work for Zaman Today, things got grim,” Atasever said. “A few of them surrounded me and started shouting death threats at me. They told me ‘we will kill you, you are dead’.”

“Thanks to immediate police intervention I managed to get away unhurt,” he added.

More than ever before, Turks all over the world have seen their diaspora communities divided between supporters and critics of Erdogan.

At around half a million people, the Netherlands has one of the largest Turkish communities in Europe. In the days after the coup, thousands of Dutch Turks took to the streets in several cities to show their support for the Turkish president. Turks critical of the Erdogan government had told media that they’re afraid to express their opinions due to rising tensions.

People suspected of being supporters of the opposition Gulen movement, led by Erdogan’s US-based opponent and preacher Fethullah Gulen, which has been accused of being behind the coup attempt, have been threatened and physically assaulted in the streets. The mayor of Rotterdam, a city with a large Turkish community, urged Dutch-Turks to remain calm and ordered increased police protection of Gulen-aligned Turkish institutions.

The men who had threatened Atasever were arrested, but released shortly afterwards. Atasever said he has pressed charges against them. He still receives threats on social media every day: he has been called a traitor, a terrorist and a coup supporter on Twitter. His photo and contact details have been shared on several social network sites accompanied by messages like “he should be hanged” and “let’s go find him”.

On 1 August Zaman Today’s Dutch website was hit by a DDoS attack and knocked offline for about an hour. An Erdogan supporter reportedly had announced an attack on the website earlier via Facebook, and Zaman Today announced it will be pressing charges.

It hasn’t just been journalists of Turkish descent who have been attacked. During a pro-Erdogan demonstration at the Turkish Consulate in Rotterdam, a TV crew for the Dutch national broadcaster NOS was verbally harassed by a group of youth. NOS reporter Robert Bas told the network that his cameraman had been assaulted and their car was also damaged. “There’s a very strong anti-western media atmosphere here,” Bas said in a live TV interview at the scene.

The Dutch Union for Journalists (NVJ) is worried about growing intimidation of journalists in the Netherlands, NVJ chairman Rene Roodheuvel said in Dutch daily Trouw. “The political tensions at the moment in Turkey and the attitude towards journalists there may in no circumstance be imported into the Netherlands,” he said. “We are second in the world when it comes to press freedom. Media freedom is a great good in the Dutch democracy and it must always be respected.”

“AKP supporters believe that media, especially in the west, are part of an international conspiracy to overthrow Erdogan,” Atasever said. Being a journalist for Zaman Today, he is not new to receiving threats. Many Turks feel the Western media is “the enemy”, he explained. “But we are even worse because we are of Turkish descent. They see us as traitors of our country.”

The government took control of the Turkish edition of Zaman in March 2016. Zaman was a widely distributed opposition newspaper, and very critical of the Erdogan government. The paper had ties with Gulen, who has denied any involvement in the coup attempt, but the Turkish government accuses him a running a parallel government. Zaman and its English-language edition, Today’s Zaman, have since been turned into a pro-government mouthpiece.

Most of Zaman’s foreign editions, however, have so far avoided government control. Zaman has editions in different languages around the world. The Dutch edition, Zaman Vandaag, with a circulation of 5,000, has managed to keep its editorial independence.

While independent journalists in Turkey are being arrested one by one, journalists of Turkish descent in the Netherlands are starting to worry too. “I know for a fact that our names have been given to the Turkish government by Dutch AKP supporters, labelling us as traitors and enemies of the state,” said Atasever, who has no plans to travel to Turkey.

“If our names are on a wanted list, which I expect they are, we will be arrested as soon as we set foot in Turkey.”

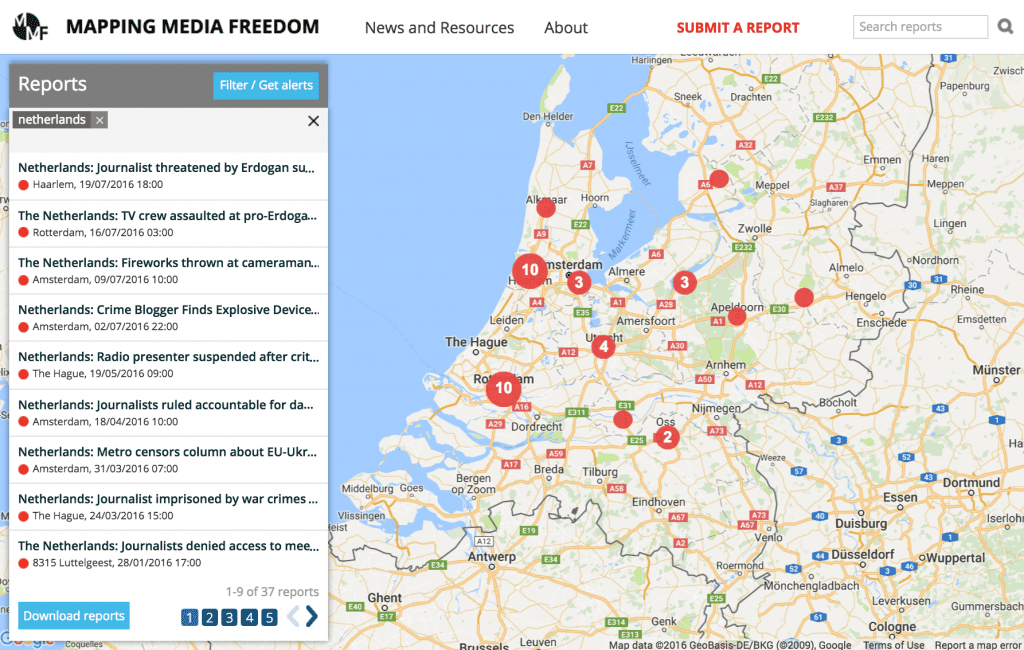

Mapping Media Freedom

|