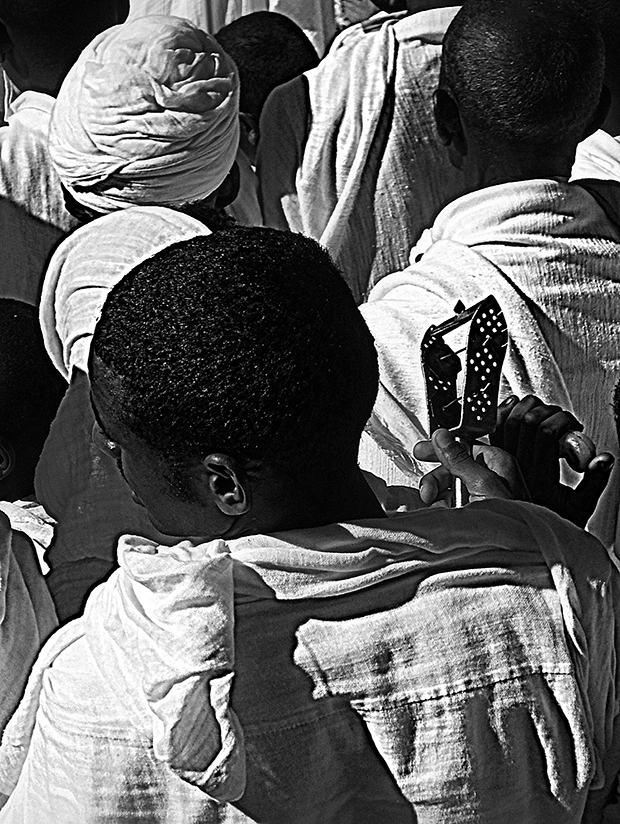

Scenes from Eritrea, photographs by Yonatan Tewelde

It initially sounded like a joke; gradually it got serious and then tragic. A decade and a half later, it is catastrophe.

Fifteen years ago on 18 September, 2001, fellow students of University of Asmara and I were confined in two labour camps, GelAlo and Wi’A, for defying a requirement of unpaid summer work. We were kept in the camps, under harsh, atrocious living conditions and open to the weather that normally reaches 45 C (113 F) for about five weeks. As we were preparing to return home, we learned the government had banned seven private newspapers and imprisoned 11 top government officials.

The day after our homecoming, beaten down and demoralised, I went to meet Amanuel Asrat, chief editor of Zemen newspaper. About 10 days before that, he had received an article, in which I detailed our living conditions, that I had managed to get smuggled out of the prison camp. My piece was published in the last issue of the newspaper.

An atmosphere of fear pervaded Asmara. The environment had changed abruptly from heated and loud political debates to people resigning themselves to whispers and silence.

Unlike our previous meetings when Asrat greeted me with a joke, this time his dejection was obvious.

I do not remember exactly what we talked about, nor do I remember where we met. I assume Asrat must have expressed satisfaction about my safe return (as two students had died in the camp) and perhaps asked about my family. It’s possible we talked about the days before we had been sent to the prison camp. I do not know.

Yet, I remember vividly that we briefly talked about the letter I had sent him from the camp, and him explaining why he had published it anonymously. He didn’t want to incriminate me in its publication. Asrat also assured me that he had destroyed the original letter after publishing it.

What else do I remember from that encounter? Nothing substantial apart from him saying in a resigned tone, “Things are getting worse. It is inevitable we [the journalists] will also follow the political leaders [who had been imprisoned].”

At that point, we went our separate ways, probably hoping to meet some days later.

Before a second meeting with Asrat, I received the news of his and other journalists’ arrests. Even then, no one thought they would be held for more than a few days or weeks.

This is why journalist Dawit Habtemichael showed up at his workplace the next morning — even after security had come to his home the previous day and hadn’t found him. He reasoned that they would arrest him and release him shortly thereafter, a common occurrence at the time. He arrived confidently at his office, prepared to be arrested. He probably felt that fleeing would be an act of betrayal to his colleagues and friends.

Contrary to expectations, both Habtemichael and Asrat have been kept incommunicado in secret prisons with 10 other journalists and 23 political figures for the last 15 years. The Eritrean authorities have never clarified their fates, but some allegedly leaked information by an anonymous whistleblower indicates that only 15 of the total 35 prisoners are alive in the worst living conditions. The journalists who were incarcerated in connection with the press crackdown in 2001 are: Amanuel Asrat, Idris Said Aba’Are, Seyoum Tsehaye, Yousif Mohammed Ali, Said Abdelkadir, Medhanie Haile, Dawit Isaak, Dawit Habtemichael, Matheos Habteab, Fessaha “Joshua” Yohannes, Temesegen Ghebereyesus, and Sahle “Wedi-Itay” Tsegazeab. The leaked source allegedly states only five of the 12 were alive in deteriorating health conditions as of the beginning of this year.

So until the arrested journalists were transferred to an unknown prison outside the capital, many of us – and maybe even those who had been arrested – had high hopes that things would normalise and they would shortly be released from detention. Apart from the architects of repression, nobody guessed that the reign of terror and fear would last for 15 years – and continue to this day.

The culture of fear and hushed whispers gradually pervaded Eritrea until it became the nation’s signature reality. All roads began leading to dead ends. Silence and lack of cooperation became the only means of defiance that would not lead to arrest and imprisonment. The regime’s elimination of all independent media operating in the country conspired with a lack of public forums to effectively zombify Eritreans living inside the country.

Now it has reached a stage where failure to applaud unconditionally all actions taken by the government, no matter how irrational or arbitrary, can be considered as dissidence.

Over the last 15 years Eritreans have been pushed to the edge. Fear has been internalised. Nationals living inside the country are beaten down to docility and respond to orders and requirements without question. The country is plagued with harsh living conditions as a result of shortsighted policies, tattered institutions and a ragged social fabric characterised by mistrust.

Unlike 2001 when I was confident that the journalists would be released after a short time, in January 2015, I celebrated as miraculous the release of Radio Bana journalists after six years in prison without charges. Of course, I had no doubt they were all innocent, and the release of an earlier batch two years before confirmed this fact. Among them was a man who had been imprisoned for four years in place of another man who shared the same first name. In another nonsensical interrogation, related by one of the Radio Bana journalists who were released, authorities showed a print article as evidence of a broadcast allegedly aired by the opposition radio station.

No matter how long the Radio Bana journalists had stayed in prison or the sufferings they had gone through, their release was still big news to celebrate. Any release of political prisoners has been a rare occurrence in Eritrea, which is why many of us called the freed journalists to congratulate them. In a system that follows the perverted logic of “guilty until proven innocent,” it was important to celebrate their freedom because no one can guess the irrational acts the regime repeatedly takes.

With the state media parroting ceaseless propaganda and hate-filled editorials, citizens have mastered a special skill: how to read between the lines. Most Eritreans do not listen to what the president says in his regular, repetitious interviews with the national media. Rather they read his gestures, listen to his tone and scan his appearance to get a feel for the state of the country. Many Eritreans check the media just long enough to determine whether he looks healthy or not.

This accumulation of fear, with a stifled media and ubiquitous censorship, has earned Eritrea the title of “most censored country in the world”, according to Committee to Protect Journalists. It also has placed it as the last country in World Press Freedom Index, as reported by Reporters Without Borders.

More about Eritrea

Letter: Eritrea must free imprisoned journalists

Escape from Eritrea: Ismail Einashe

Scenes from Eritrea, photographs by Yonatan Tewelde

Yonatan Tewelde is an Eritrean photographer and filmmaker who is also working as PEN Eritrea in Exile’s webmaster and graphic designer