Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Campaigning for a free Eritrea since the age of 16, Vanessa Berhe can even count the Pope as a supporter. After founding One Day Seyoum to campaign for the release of her uncle, the Eritrean photojournalist Seyoum Tsehaye, Berhe has followed her uncle’s path, becoming a strong voice fighting for freedom in Eritrea.

|

|

“Eritrea has never had television,” says journalist Seyoum Tsehaye in a video interview filmed in 1994, three years after the country had won its independence. “This country waged a 30 years war, so it was completely devastated. There was no life in Eritrea, it was only a life of resistance. We resisted and we had a victory.”

The interview shows a hopeful Seyoum set on bringing television and free media to the Eritrean people. A few years later, in 2001, Seyoum and 10 Eritrean journalists were imprisoned without trial. They are still in prison today.

Their story is being forgotten, Berhe believes. Seyoum Tsehaye’s niece, Berhe’s parents were exiled from Eritrea during the 30 years of civil war. She grew up in Sweden, and at the age of 16 founded One Day Seyoum, a campaign to get her uncle out of prison.

“I was telling my friends in school about how my uncle has been imprisoned because of his journalism, and was astonished by the fact that people are so interested and passionate about this case,” Berhe told Index.

“Because Seyoum’s government let him down, the rest of us have to unite, go beyond borders, nationalities and skin colour and prove to Seyoum that he is our brother,” she said when she launched the campaign.

Tsehaye has never formally been charged with a crime, had a trial or been allowed visits from family. Little is known about where he is held, and his family has heard nothing from him since he went on hunger strike in 2002.

One of many prominent journalists to be arrested in 2001, Eritrea has had no independent media since, with only ministry of information-approved media allowed in the country. Press freedom in Eritrea is consistently ranked the lowest in the world, surpassing North Korea in its restrictions.

Berhe’s One Day Seyoum campaign uses social media, video, petitions, speaking engagements and offline actions to spread its message. Berhe has also worked to build a network of ambassadors across the world to help share her message – she now has more than 70 ambassadors across Europe, Asia, Africa, South America and North America.

And she has even had the support of the Pope. Representing Eritrea in a conference about illegal human trafficking at the Vatican, she had the chance to meet him. “I saw him and I brought a paper, took a pen and just wrote ‘I am the Pope and Seyoum is my Brother’… I told him about the case and he supported it of course and took a picture.”

She also used the opportunity to launch a second campaign, Free Eritrea. “With that campaign we aim to raise awareness about crucial issues that are going on with Eretria that also are being forgotten; national service, Eritrean refugees, the lack of freedom of religion, expression, and all those vital human rights that are being violated.”

When asked what her plans were in 2016, Berhe answered “We’re planning to free him.”

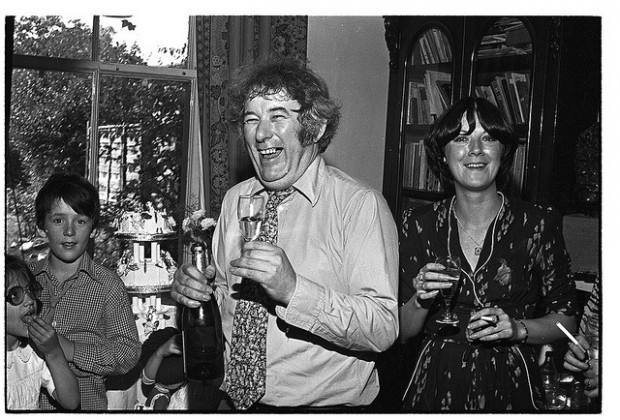

Seamus Heaney with his family and at a party at home in Dublin, 1979. Photographer: Bobbie Hanvey

It’s the 17th annual World Poetry Day, which was first declared by Unesco in 1999 to help meet the world’s aesthetic needs by promoting the reading, writing and teaching of poetry. This year, Unesco director-general Irina Bokova said: “By paying tribute to the men and women whose only instrument is free speech, who imagine and act, Unesco recognises in poetry its value as a symbol of the human spirit’s creativity. […] The voices that carry poetry help to promote linguistic diversity and freedom of expression.”

One poet of this calibre was Seamus Heaney.

The Irish poet, playwright and lecturer was as prolific a translator of poetry as he was a writer. In September 1998, his translation of Gile na Gile, a poem written by Irish language poet Aodhagán Ó Rathaille (1670–1726) was published exclusively in Index on Censorship under the title The Glamoured.

“It is a classic example of a genre known as the aisling (pronounced ashling) which was as characteristic of Irish language poetry in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as rhymed satire was in England at the same time,” Heaney wrote in Index. “The aisling was in effect a mixture of samizdat and allegory, a form which mixed political message with passionate vision.”

This month, Heaney, who died in August 2013, offers us a gift from the afterlife: the publication of his translation of Aeneid’s Book VI, the Roman poet Virgil’s epic on mythic Trojan Aeneas’s journey to Hades. In the poem, Sibyl of Cumae, a guide to the underworld, “chanted menacing riddles” in an attempt to confuse our hero:

Then as her fit passed away and her raving went quiet,

Heroic Aeneas began: ‘No ordeal, O Sibyl, no new

Test can dismay me, for I have foreseen

And foresuffered all. But one thing I pray for

Especially: since here the gate opens, they say,

To the King of the Underworld’s realms, and here

In these shadowy marshes the Acheron floods

To the surface, vouchsafe me one look,

One face-to-face meeting with my dear father.

In the introduction to Aeneid’s Book VI, published posthumously, Heaney describes the poem – which he began working on in 1986 after the death of his father – as “like classics homework, the result of a lifelong desire to honour the memory of my Latin teacher at St Columb’s College, Father Michael McGlinchey”.

St Columb’s is a Roman Catholic grammar school for boys in Derry. Heaney formed part of the school’s “golden generation” in the 1940s and 1950s, which included the dramatist Brian Friel and politician John Hume.

When I attended St Columb’s between 1999 and 2006, pupils were reminded of the school’s alumni illustrissimi — especially Nobel laureates Heaney and Hume — at many a class, assembly and function. One of the highlights of my time as a pupil was attending an after-school discussion with Heaney and the classicist Peter Jones. They spoke of the positive effect reading poetry has on thought processes and the irrelevancy of the poet’s intention when a reader encounters the poem. It is, he said, our own unique experience with a work that truly matters.

Afterward, Heaney signed my copy of Redress of Poetry, a collection 10 lectures he gave between 1989 and 1994 while a professor of poetry at Oxford.

“Poetry cannot afford to lose its fundamentally self-delighting inventiveness, its joy at being a process of language as well as a representation of things in the world,” Heaney writes in the opening chapter. “[P]oetry is understandably pressed to give voice to much that has hitherto been denied expression in the ethnic, social, sexual and political life.”

Redress of Poetry’s predecessor, the collection of literary criticism essays from 1978-1987 titled Government of the Tongue, discusses in much more depth those who have been denied such expression in their political and social lives. The book is perhaps best known for its celebration of poets of the Eastern Bloc, the former communist states of central and eastern Europe. The discovery of poets such as Czesław Miłosz, Osip Mandelstam, Joseph Brodsky and Zbigniew Herbert had an impact on Heaney’s own work. As a Northern Irish Catholic, Heaney could easily identify with the religion, culture and history of Polish poets Miłosz, whose work was banned by Poland’s communist government, and Herbert, who organised protests against censorship in the Eastern Bloc.

One poem Heaney references is Miłosz’s Child of Europe, which reads:

We, from the fiery furnaces, from behind barbed wires

On which the winds of endless autumns howled,

We, who remember battles where the wounded air roared in

paroxysms of pain.

We, saved by our own cunning and knowledge.

It brings to mind the experiences of many in Northern Ireland. Throughout the Troubles, Heaney was known for expressing both clarity and humanity amid chaos. He tells a story in Government of the Tongue, however, of his personal difficulties in creating art amid violence. He was on his way to a recording session at the BBC studios in Belfast sometime in 1972 with folksinger David Hammond when the pair heard bombs go off.

“[T]he very notion of beginning to sing at the moment when others were beginning to suffer seemed like an offence against their suffering,” he wrote.

This tension in the poet’s mind seemingly had no bearing on his ability to capture the mood of an entire nation through his work. In The Cure at Troy, Heaney’s telling of Sophocles’ Philoctetes, the story of how Odysseus tricked Achilles’ son into joining the Greek forces at Troy, expressed the hope felt by many in his country in 1991, a year of ceasefires and all-party talks.

The poem contains the often-quoted and poignant words:

History says, don’t hope

On this side of the grave.

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up,

And hope and history rhyme

It’s hard for many of us to imagine, but all around the world, people are being intimidated out of playing music. Here is a list of some musicians who have been prevented from expressing themselves freely so far in 2016.

Ahmet Muhsin Tüzer, Turkey

The Turkish musician was denied permission to perform in Portugal by Turkey’s Directorate of Religious Affairs, according to several news media, on 1 March 2016. His performance at the Serralves Museum in Porto had been approved by Turkey’s Cultural Ministry before the Diyanet, Turkey’s religious enforcement authority, overruled their decision.

Bangy (Cedric Bangirini), Burundi

Cedric Bangirinama, known as Bangy, was arrested on 27 January 2016 by Burundi’s national intelligence service for statements he made on his Facebook account that were insulting to the head of state. The musician was held for three weeks and eventually released on 16 February 2016.

Elawela Balady, Egypt

A concert scheduled for 24 January 2016, celebrating the fifth anniversary of the Egyptian Revolution, was to forced to cancel by the country’s Ministry of State of Antiquities. The event was to feature Elawela Balady and had received approval from the Ministry of Culture to hold the show in Cairo’s Prince Taz Palace. The band that was set to play have contributed to political and social awareness through their music.

Art Attack, Kenya

Art Attack, a Kenyan band who campaign for LGBT rights in the country and other African nations, faced censorship after the Kenyan Film and Classification Board banned their video in February for its remix of Macklemore and Ryan Lewis’s song Same Love. The decision was made because the video “does not adhere to the morals of the country”, Kenyan newspaper The Star reported. The video includes powerful images of LGBT protests and homophobic news headlines from the country.

Salar Aghili, Iran

Salar Aghili was banned from performing at Iran’s Fajr International Music Festival and from appearing on Iranian television because of his appearance on a Persian-language satellite channel based in London. Ali Jannati, minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance, said earlier this month that “artists shouldn’t give any interviews to foreign satellite channels”.

Index on Censorship has teamed up with the producers of an award-winning documentary about Mali’s musicians, They Will Have To Kill Us First, to create the Music in Exile Fund to support musicians facing censorship globally. You can donate here, or give £10 by texting “BAND61 £10” to 70070.

Blogger and human rights activist Dr Abduljalil Al-Singace has been in prison in Bahrain since 2010. He was arrested at Bahrain International Airport after returning from London, where he had been testifying to the House of Lords about Bahrain’s human rights practices. A security official stated that Al-Singace had “abused the freedom of opinion and expression prevailing in the kingdom”. After being held in solitary confinement for six months, Al-Singace was briefly released in February 2011 before being rearrested in March.

|

|

“I saw them drag him in his underwear and without his glasses, with a gun pointed at his head,” a relative said of the arrest. He was taken to a detention center where he was blindfolded, handcuffed and beaten. On 22 June 2011 a military court sentenced Al-Singace to life imprisonment.

Al-Singace is one of 13 leading human rights and political activists arrested in the same period, subjected to torture, and sentenced in the same case, known as the “Bahrain 13”. All 13 are all serving their prison sentences in the Central Jau Prison.

“The group is more like a family now,” said a member of Dr Abduljalil Al-Singace’s family, who asked to remain unnamed due to pressure the family continue to face from authorities. “They went through similar conditions of the arrest and torture, and they all suffered a lot because of their opinions and because of expressing their opinion.”

Last year Al-Singace went on hunger strike to protest the treatment of prisoners in Bahrain. Al-Singace, suffers from polio in his left leg and various other health issues, was held in solitary confinement in a windowless room in Al-Qalaa hospital and has denied any form of media or writing materials.

“Being alone in solitary confinement in that small room, not being allowed to watch TV or to talk to other patients or have books, it didn’t break anything in him,” said the family member. “I think it made him stronger. He was always positive during the whole period.”

Al-Singace’s hunger strike lasted for 313 days.

“He inspires everyone. Even when he was very weak during the strike, he was the one who was inspiring us. We felt stronger with his strength despite that his body was very weak and he was shivering, but he has this very, very positive strong spirit.”

And the situation in Bahrain at the moment?

“It is still difficult. There are still people being arrested, children being arrested, nationalities being revoked. It’s still very complicated and very difficult. You still see police cars and checkpoints especially in the villages or in the openings of the villages, the entrances. It’s still very difficult in Bahrain.”