Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Dutch journalists have been ringing alarm bells about violations of media freedom at public asylum debates throughout the country. Several journalists and broadcasters claim they have been banned from debate evenings in small towns across the country by local authorities. In one instance, a village municipality placed a five-kilometer-wide exclusion zone around the area where the debate took place.

On 28 January 2016, Allard Berends, editor-in-chief of regional broadcaster Omroep Flevoland, received a call from one of his reporters. A citizens’ debate about the possible housing of refugees in the village of Luttelgeest, in the centre of the country, was about to start.

But there was a problem.

“We already knew that journalists were not welcome inside,” Berends told Index on Censorship. “So my reporter was standing outside, on the public ground.” But while conducting street interviews, his reporter and cameraman were approached by two police officers. They told to leave the village because an emergency decree recalled Berends, who’s in charge of the leading radio and TV broadcaster in the province of Flevoland.

“I have a long career in journalism,” he said. “But I’ve never experienced something like this before. It was just ridiculous. It was Kafkaesque.”

According to documentation brought to the journalists by the police officers, the emergency decree was declared by Luttelgeest’s mayor and stated that only people who were invited were allowed inside. Nobody else — including journalists — was allowed to get closer than five kilometres around the area where the citizens debate was held.

The municipality of Luttelgeest had told Omroep Flevoland that an emergency decree was in place to prevent possible turmoil and to give citizens the privacy to say what they want. “This is an unacceptable explanation,” Berends explained. “It crosses the borders of press freedom and should not be possible in this country.”

While Europe is coping with the largest migration crisis since the Second World War, the arrival of thousands of refugees has caused tension in the Netherlands, as it has in other European countries.

The Netherlands made international headlines with a series of incidents. In October 2015, hooligans attacked an asylum centre near the city of Utrecht, where the majority of refugees housed there were Syrian. In December, a meeting of the council in the town of Geldermalsen to decide on the building of a centre to house 1,500 asylum seekers descended into riots. The police fired warning shots, with live ammunition, to disperse a crowd of opponents, chanting anti-migrant slogans. In several other towns and villages, violent protests broke out against plans to build housing for asylum seekers.

Local governments across The Netherlands have had difficulties trying to sell the moral case for housing asylum seekers to a sceptical and often angry electorate. In a bid to include local people in the debate, citizen debate evenings have become a regular fixture in recent months. But on several occasions they have been marred by confrontation and violence, often in front of watching TV cameras.

The incident in Luttelgeest is not an isolated case. In Geldermalsen, journalists were restricted from covering the citizen debates, too. A radio reporter for the national broadcaster NOS tweeted that he was denied entrance to the public debate at the Geldermalsen town hall. According to the report, a security guard had been instructed to “keep the NOS away from the area.” And a municipality spokesperson had reportedly told the journalist the “press doesn’t interest us at all” and “if you want to follow the debate, that is your problem, not mine”.

In the city of Harderwijk journalists were not allowed to record audio or video at a public meeting concerning housing for 800 asylum seekers in the town. Those who refused to comply with the order, it was reported, were told that they would be removed from the venue.

At a similar meeting in the southern town of Heesch, most journalists were simply denied entry. The municipality’s media department had made a strict selection, only allowing a few journalists in.

Similar cases have been reported in the cities of Kaatsheuvel and Utrecht.

The Dutch Association of Editor In Chiefs (Het Nederlands Genootschap van Hoofdredacteuren) have published a statement expressing their concern about the restrictive media policies now being adopted by local governments.

“In an open and democratic society, it is up to the media to decide what to report on, how to report and what methods to use,” they wrote in a statement. “We acknowledge tensions surrounding the refugee debate in the Netherlands. But these tensions exist within the debate itself and in all the interests and emotions involved, not in the reporting of it. Restricting the media should never be the answer.”

The letter was initially addressed to the mayor of the municipality of Bernheze, of which the village of Heesch is part of. But it soon turned into a public statement towards all local governments. The letter also condemns that “local governments more and more seem to want to decide which journalist is allowed access and which journalist is not”.

The Dutch Union of Journalists (NVJ) agrees. “It is just wrong to differentiate between visual, audiovisual and written media at meetings in which the public is being informed by local governments,” NVJ spokesman Thomas Bruning told Index on Censorship.

The incident in Luttelgeest, in which journalists were not only banned from a public debate but also denied access to an entire village, is considered particularly alarming by the NVJ.

“The press was not even allowed to talk to citizens and politicians before and after the debate,” Bruning said. “Using an emergency decree is really not worthy of a democratic constitutional state.”

The NVJ has sent letters of complaint to all the municipalities involved.

The Omroep Flevoland editor-in-chief Berends announced that he will go to court and press charges against the mayor of Luttelgeest, who was responsible for issuing the emergency decree.

“I want to ask a judge what he thinks of a mayor who declares an entire village a no-go area for journalists,” said Berends. The NVJ is supporting Omroep Flevoland in court.

On that January evening, Omroep Flevoland was not able to report from the debate about a possible centre for asylum seekers in Luttelgeest.

“We were able to speak to some citizens and council members the day after,” Berends said.

The debate passed off calmly. “But really, we should have been there,” added Berends. “It is the essence of our profession, we observe and report what we have heard and seen.”

This article was originally published at Index on Censorship.

Mapping Media Freedom

|

Umberto Eco, March 2010, Paris. Credit: Flickr / Abderrahman Bouirabdane

I am of the firm belief that even those who do not have faith in a personal and providential divinity can still experience forms of religious feeling and hence a sense of the sacred, of limits, questioning and expectation; of a communion with something that surpasses us.What you ask is what there is that is binding, compelling and irrevocable in this form of ethics.

I would like to put some distance between myself and the subject. Certain ethical problems have become much clearer to me by reflecting on some semantic problems – don’t worry if people say this discourse is difficult; we are perhaps encouraged into easy thinking by the ‘revelations’ of the mass media, which are, by definition, predictable. Let people learn to ‘think difficult’ because neither the mystery nor the evidence are easy to deal with.

My problem was whether there were ‘semantic universals’, or basic concepts common to all humanity that can be expressed in all languages. Not so obvious a problem once you realise that many cultures do not recognise notions that seem obvious to us: for example, that certain properties belong to certain substances (as when we say ‘the apple is red’) or concepts of identity (a=a). I became convinced that there certainly are concepts common to all cultures, and that they all refer to the position of our body in space.

The article is available for free until the end of March. To read it in full, click here.

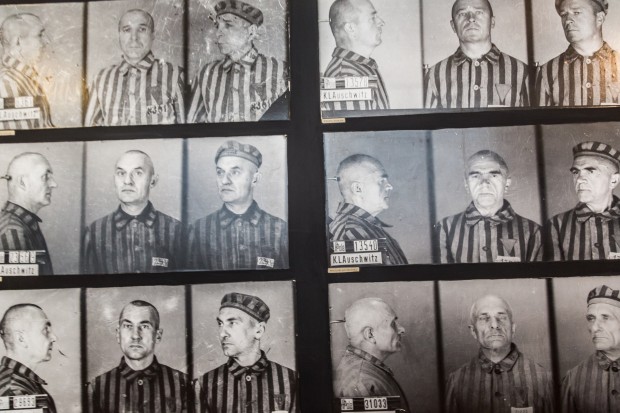

Still from an Auschwitz exhibition, 22 July 2014 in Oswiecim, Poland

When discussing academic freedom more than a century ago, German sociologist and philosopher Max Weber wrote: “The first task of a competent teacher is to teach his students to acknowledge inconvenient facts.” In Poland today, history appears to be an inconvenience for the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party, which is introducing legislation to punish the use of the term “Polish death camps”.

The Polish justice minister Zbigniew Ziobro announced earlier this month that the use of the phrase in reference to wartime Nazi concentration camps in Poland could now be punishable with up to five years in prison. If enacted, Poland would find itself in the unique position of being a country where both denying and discussing the Holocaust could land you in trouble with the law. Holocaust denial has been outlawed in Poland — under punishment of three years “deprivation of liberty” — since 1998.

Any suggestion of Polish complicity in Nazi war crimes against Jews brings with it, in the party’s own words, a “humiliation of the Polish nation”.

Of course, Poland was an occupied country which suffered terribly under Nazi Germany, so any talk of acquiescence understandably hits a nerve. As all good history students know, however, the discipline has its ambiguities and competing theories, from the acclaimed to the crackpot, and singular, simplistic narratives are rare. But few democratic countries in the world punish those who argue unpopular historical positions. Which is why legislating against uneasy truths is the same as legislating against academic freedom.

Two recent examples show the Polish government of doing just this. Firstly, Poland’s President Andrzej Duda made public his serious consideration to stripping the Polish-American Princeton professor of history at Princeton University Jan Gross of an Order of Merit — which he received in 1996 both for activities as a dissident in communist Poland in the 1960s and for his scholarship — over his academic work on Polish anti-Semitism. Gross outlined in his 2001 book Neighbors that the massacre of some 1,600 Jews from the Polish village of Jedwabne in July 1941 was committed by Poles, not Nazis. More recently, the historian has claimed that Poles killed more Jews than they did Germans during the war, which prompted the current action against him.

Some who disagree with his arguments have labelled Gross an “enemy” of Poland and a “traitor to the motherland”. The historian has hit back, saying in an interview with the Associated Press: “They want to take [the Order of Merit] away from me for saying what a right-wing, nationalist, xenophobic segment of the population refuses to recognise as facts of history.”

Academics too — Polish and otherwise — have come to his defence. Agata Bielik-Robson, professor of Jewish Studies at Nottingham University, points out that a “democracy has to have a voice of inner criticism”. She is worried that PiS is seeking to do away with such criticism in order “to produce a uniform historical perspective”.

Polish journalist and former activist in the anti-communist Polish trade union Solidarity Konstanty Gebert explained to Index on Censorship that PiS has made “convenient scapegoats” of people like Gross. “PiS is moving fast to reestablish a ‘positive narrative of Polish history’ by breaking with an alleged ‘pedagogy of shame’,” he said.

The party first tried — unsuccessfully — to outlaw the term “Polish death camps” in 2013 when it was in opposition. Should the law now pass, and you need help adhering to the proposed rules, the Auschwitz Museum has released an app to correct any “memory errors” you may experience. It detects thought crimes such as the words “Polish concentration camp” in 16 different languages on your computer, keeping you on the right track with prompts asking if you instead meant to write “German concentration camp”.

Poland may have lurched to the right with the election of PiS last October, but the party’s authoritarianism — from crackdowns on the media to moves to take control of the supreme court — seems positively Soviet in some respects. Attempts to control history, too hark back to the Polish People’s Republic of 1945-1989, when, in the words of Elizabeth Kridl Valkenier in the winter 1985 issue of Slavic Review, “cultural patterns” and “habits of mind” made it impossible to make historical interpretations “alien to that national sense of identity and a methodology at odds with the canons and objective scholarship”.

Gebert sees similarities between current and communist-era propaganda “in the basic formulation that there is nothing to be ashamed of in Polish history, and in Polish-Jewish relations in particular, and in the belief that there is one correct national viewpoint”.

However, now that freedom of speech exists, the government can and are being criticised for their actions. “This puts the government propaganda machine on the defensive,” Gebert said.

Just last week, President Duda spoke against the “defamation” of the Polish people “through the hypocrisy of history and the creation of facts that never took place”. He has made his motives clear: “Today, our great responsibility to create a framework […] with the dual aim of fostering a greater sense of patriotic pride at home while enhancing the country’s image abroad.”

It should be intolerable for the freedoms of any academic subject to be impinged for ideological ends. If academic freedom is to mean anything, it should include the right to tell uneasy truths, get things wrong and have you work challenged by the highest academic standards.

There’s only one place to turn for PiS to find an example of best practice on how to challenge Gross’ research, and that is to the very body the party will grant authority to on deciding on what is and isn’t a breach of the law regarding “Polish death camps”. Poland’s Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) produced several reports between 2000-03 challenging claims in Gross’ book on the Jedwabne massacre. It used research and reason — as opposed to censorship — to make the case that the historian didn’t get all the facts right. It found, for example, that German’s played a bigger part in the slaughter than Gross had claimed, and that the numbers killed were more likely to be around the 340 mark, rather than 1,600.

IPN should tread carefully, though. Any inconvenient truths with the potential to humiliate the Polish people could one day soon see it branded a “traitor”.

Acrassicauda concert at The Roxy in Hollywood, 10 June 2010. Credit: Flickr / Bruce Martin

Underground music scenes have begun sprouting up in many countries around the world in the last few years, where previously no such thing existed. These movements have managed, in many cases, to continue despite a continuing trend of censorship in the arts and government repression. Whether it be punks in Indonesia rebelling against Sharia law or hip-hop artists in Mumbai rapping about independence from Britain, people all over the world are fighting for their right to artistic freedom. Here are a few cities around the world where musicians refused to be silenced.

Even after social activist and creator of The Second Floor, a cafe that promotes discussion, performance and art, Sabeen Mahmud was murdered by armed motorcyclists in Karachi in April 2015, the experimental and electronic music culture has continued to grow. Refusing to be intimidated into silence, artists like Sheryal Hyatt, who records as Dalt Wisney and founded Pakistan’s first DIY netlabel, Mooshy Moo, and the producing pair of Bilal Nasir Khan and Haamid Rahim, who created the electronic label and collective Forever South, are challenging conventional ideas about the music culture in Karachi.

Punk music is one of the ultimate forms of expressing disdain for a system of oppression, so it comes as no surprise that so many youths in Indonesia have embraced the genre with a passion. The punk scene, which grew exponentially following the 2004 tsunami when a great many lost family members and help from the government was less than forthcoming. The hostility and discrimination against the punk subculture came to a head in 2012 when police rounded up 64 youths at a concert, arrested them and took them to a nearby detention centre to have their mohawk hairstyles forcibly shaved. Despite this, bands like Cryptical Death continue to promote their scene and pen songs about resisting repressive government figures.

The vitality of punk music is also present in Burma, where musicians have been advocating for human rights through fast-paced music since around 2007. No U Turn and the Rebel Riot are popular punk groups that routinely rail against a government that they feel is repressive and unjust. No U Turn sounds like a resurrection of Bad Religion-meets-Naked Raygun with a blend of biting lyrics and punishing speed.

Indian hip-hop pioneers have been appearing more and more in the last 10 years, with Abhishek Dhusia, aka ACE, forming Mumbai’s Finest, the city’s first rap crew, and Swadesi, another local group whose work they think represents feelings and ideals of many young people in the city. Swadesi, in particular, advocates for social justice within their band’s mission, with working for NGOs and organising events being an important element of their group.

Musicians in Iraq have faced a variety of oppressive control, ranging from young people being stoned to death by Shi’ite militants for wearing western-style “emo” clothes and haircuts to Acrassicauda, a popular heavy-metal band from Baghdad, receiving death threats from Islamic militants. Acrassicauda had to flee the country a few years after the USA invaded Iraq, going first to Syria and then to the USA, where they were given refugee status and from where they now continue to make music. They have hopes of touring the Middle East soon but have no idea when they will be able to return to Iraq.

Index on Censorship has teamed up with the producers of an award-winning documentary about Mali’s musicians, They Will Have To Kill Us First, to create the Music in Exile Fund to support musicians facing censorship globally. You can donate here, or give £10 by texting “BAND61 £10” to 70070.