[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

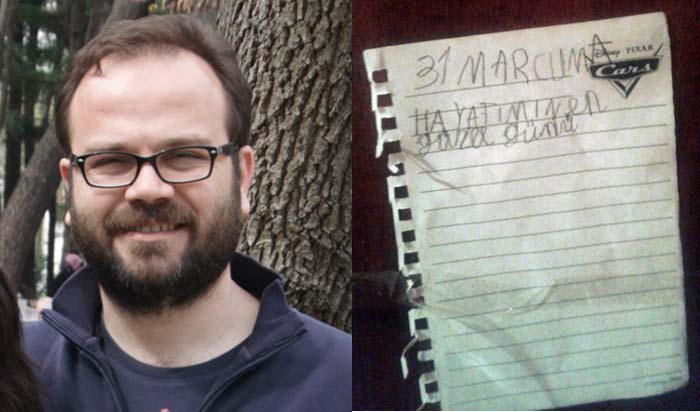

Journalist Oguz Usluer has been accused of being a terrorist. The note, from his six-year-old son, reads: “31 March Friday. The happiest day of my life.”

On 31 March 21 journalists who were charged with working for the media arm of the alleged group behind the 15 July coup attempt were released by a court ruling. Following a tweet from a pro-government troll account, the prosecutor filed an objection to the release of eight and announced that it had launched a new investigation for the other 13.

The judges who issued the release ruling were suspended about a week after the trial.

During the few hours before the new detention warrants came, their families had already driven to Silivri Prison, where they have been held for months. Among them was Sunay Usluer, the wife of a former television coordinator who was arrested in December 2016. She shared with Index on Censorship her account of the anxious hours waiting for the release that never came.

“I am planning to bring the children to the next visit after the trial.”

“But of course there is always the possibility that I might be released in the next session, although you seem not to even consider that.”

Such was the conversation I had with my husband Oğuz on Thursday 23 March, during my last prison visit before the 31 March trial hearing. This entire process had the air of a tragicomical joke; we were laughing when we should have been crying. Although for the past four months, neither of us had given up hope, we didn’t really expect a fair trial or a release ruling from the court. But, at least, we would be able to see each other for five days in a row during the scheduled trial sessions; a rare occurrence.

With this motivation, we started the five-day session marathon. The 25 people, who were on trial for membership in a terrorist organisation and who didn’t know each other in the slightest, were in the front row in the courtroom. Dozens of their family members, living 25 different human stories together with them, sat in the back of the room. Everyone wore the same exhausted expression on their face, reflecting the months fraught with ambiguity and fragile flickers of hope.

While waiting for the trial sessions that never seemed to start, or while waiting during long intervals, people who put their own identities aside and described themselves as the “wife, mother, son/daughter” of a particular journalist, started speaking about the shared-yet-separately-lived agony they have endured, after months of longing for a conversation with someone who can understand them. One of them said, “I can’t tell you how happy I am to see that people who are going through the same tribulations as me still being able to laugh,” while we laughed as we played a game of release-lotto with our lawyer.

Our lawyer has been extremely supportive in this process. He always had hope, but I was the devil’s advocate. “You say he will be released, but I will not believe that until I see him next to me.”

Court officials moved the trial to a smaller courtroom for the final three days. Family members of those on trial were allowed inside only for 15 minutes in whatever room was left unoccupied by journalists and lawyers.

On the morning of the fifth and final day, the prosecutor was reading out a list of those he recommended be released. At that moment, I caught Oğuz’s eye and made a gesture asking if he was on the list. “Yes, but it’s only the prosecutor’s request,” he said, in order to fend off the likely frustration that might follow. Fearing to have hope is worse than despair; something we have found out in this process.

At the end of the fifth day, everyone was too exhausted to even speak. While waiting for the court’s decision, only the sounds of shy seagulls from outside could be heard as if it was sinful to talk in the corridor where the 25th High Criminal Court is located. Then there was the sound of a notification on my phone, and the ticker reading “released” on a television screen. This scene was followed by 21 families, crying tears of happiness, hugging each other. People who still found the news hard to believe, relying on confirmations from each other.

“I couldn’t believe it. I walked towards the courtroom, and I asked a lawyer who I didn’t know at all if my husband is among those released. I suddenly gave him a hug when he answered yes,” somebody said.

Later, our lawyer walked out of the courtroom. His first remark took a jab at my longstanding incredulity. I still had no intention of believing that he really was to be released until he was next to me. I didn’t voice my concern in the way you think you might jinx a good thing if you say something negative. I, carrying this worry in my heart, my ten-year-old son, whom I’d brought with me so that he could at least catch a glimpse of his father, and our relatives celebrated. Oğuz’s family in İzmir were already boarding a plane to Istanbul to celebrate with us. We will most likely have picked him up from prison by the time they arrive, I thought.

We left the courthouse with a sense of joy and began driving to Silivri. Even the distance, which has become complete torture for us as we have to travel every week, felt short. Families were already waiting outside the main gate of the Silivri Prison in the anticipation of seeing their husbands, fathers and brothers again. Everyone was smiling now, carrying on conversations filled with hope despite the biting cold. One family had brought a celebratory band of drummers from Edirne, who were going to play as their relative was released. Everyone’s eyes were fixed on the main gate.

The first few hours were just like a carnival.

Then the mood changed. The crowd started to feel that something was off, but no one had the courage to speak it. In the middle of the night, vehicles that didn’t have official license plates entered the prison one after another, and all of them drove towards Section 9. Later, they set up a barricade to block the view of the parking lot that faced the main gate. A police van entered the prison. Could it be that they had brought them to the prison from the courthouse just now? At some point, armoured vehicles of the gendarmerie special operations command arrived. Wasn’t this much security a bit extreme for a handful of people?

The air of festival had left the crowd, and it had gotten much colder. Still, nobody could bring themselves to speak the fear they held. Many of them started waiting in their cars, saying it was too cold. As I waited inside the car, a friend texted me, telling me to be cautious and sent a tweet posted by some creature:

“We will take’em if you release’em,” it said.

At that moment, in the middle of the night in the Silivri cold, in what was possibly the most secure part of my country, among the gendarmerie and police officers, I feared for the life of the children playing between the parked cars despite the cold air and for the life of my own son.

Dr. Sunay Usluer and her ten-year-old son waited outside the dates of the prison for a release that never came.

What came after was a long and desperate wait; a semblance of hellish torture. All of a sudden, they forbid us to wait near the prison because of the state of emergency, and we were ordered to drive towards the highway slip road; they said those released would be brought there. In that moment, somebody worked up the courage to ask: “Is there a problem?”

“There is no problem Miss, the release procedures are being conducted inside. It’s just taking a bit of time because there are many people. Continue to wait in the area ahead.”

But that “area ahead” kept moving forward. People were constantly driven away further and further from the prison, and finally, they ended up waiting at a spot from where the slip road was invisible. At the entrance to the highway, there was a gendarmerie vehicle, guarded by two privates. Every time we asked them what was going on, they could only tell us: “We can only give you information when our commanders give us information.” At the same time, we kept checking our Twitter feeds. At this point, it became clear that no one would be released tonight, but none in the crowd could drop the slightest flicker of hope and leave, so we waited on and on and on.

There were small children and older people among those waiting. At some point, the vehicles started to leave one by one, eventually, maybe ten or fifteen vehicles remained. My son and I also gave up hope and decided to go home. But as we stopped to ask the gendarmerie private if there had been any developments one last time, we saw a police van in the distance.

We got back into the car and started driving towards the van. As we passed, we caught the attention of a dark silhouette inside the vehicle, who had leant his head against the window. When he saw us in the car, a flash of joy went through his body, he cocked his head and waved at us. It was him: a tiny miracle gave us the information that our supreme state had denied us. Oğuz had been detained again and he was being driven back to Istanbul, to the police department. The police van slowed down for us to pass it. We wanted to drive near again and take a better look, but this time plainclothes officers drove us away.

The hardest part in all of this is to try and maintain one’s composure in front of the children. My son and I lived this experience as if we were having a good time; as if we were in an adventure movie. Neither of us cried. But when we reached home in the early morning hours, we were met with a note by my six-year-old son, who is just learning to write, on the door. “31 March Friday. The happiest day of my life.” His brother and I sat down on the stairs of our building, held each other and burst into tears. How were we to explain to him why his father hadn’t come home?

This was how I saw my husband 15 days ago. After that, he and his co-defendants were kept for in detention seven days at the police station on Vatan Street in Istanbul, which was extended for another seven days. During this time, they sent us his belongings from Silivri Prison; his notes, summaries of books he wrote down. For the past months, he wasn’t allowed to send mail.

I was exhilarated as if I had gotten a pages-long letter; I even read the receipts he had kept from the prison cafeteria. There was also a to-do-list, where he wrote down what he planned to do after his release. The first item on his list was, “Don’t forget about those who remain in prison, and don’t let them be forgotten.” At the end of the day, he is a journalist.

The process that followed was the same as before, police interrogation, another desperate wait at the Çağlayan courthouse during the prosecutor’s questioning and court interrogation, again “what if”; once again disillusionment and ambiguity. What happened to the previous panel of judges only shows the extent of independence of our judiciary and sets the maximum for our expectations.

At the end, they were rearrested on new charges, a decision that didn’t really surprise us. All we could do was say, at least they are back in Silivri Prison, back to their routine, sleeping in a normal bed [as opposed to detention conditions]. I woke up on Saturday and called the prison to find out if they had moved him to a different cell. “Nobody was brought here last night,” the voice at the end of the line said.

I later found out that the police, which drove back to Silivri in a convoy without wasting a second to re-arrest them on the night of 1 April — were simply too lazy to drive back to Silivri on 16 April and they dumped my husband — my partner of 12 years, the father of my children, a yeoman journalist who dedicated 20 years to reporting the news — at Metris Prison [in central İstanbul] like some piece of baggage dropped at storage for safe keeping.

Period.

Dr. Sunay Usluer

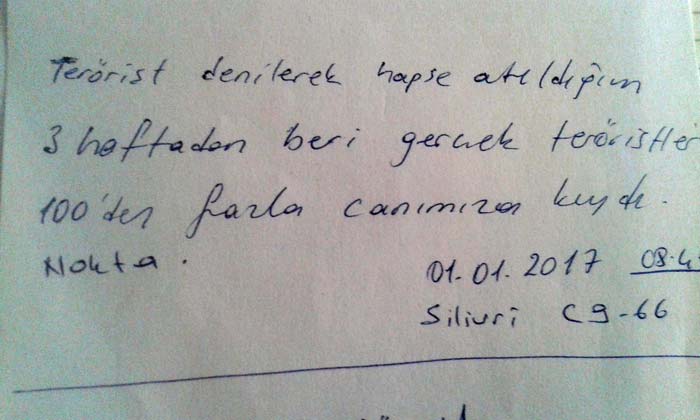

“In the past three weeks, during which I have been imprisoned being declared a terrorist, real terrorists have taken away 100 lives from us.”

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1493981743376-3f86911a-75c7-0″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]