[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

“We must distinguish the things that are intellectually dishonest and aimed at persuading, which is traditionally called propaganda, and the things where people are trying to give you general information, which doesn’t have the absolute intention of persuading you,” said The Times columnist David Aaronovitch at a panel at the Essex Book Festival.

Aaronovitch, also Index’s chair, was discussing the role of propaganda with leading expert on the darknet and technology Jamie Bartlett and Chinese-British author Xinran, who was the first woman to have a late-night radio show in China.

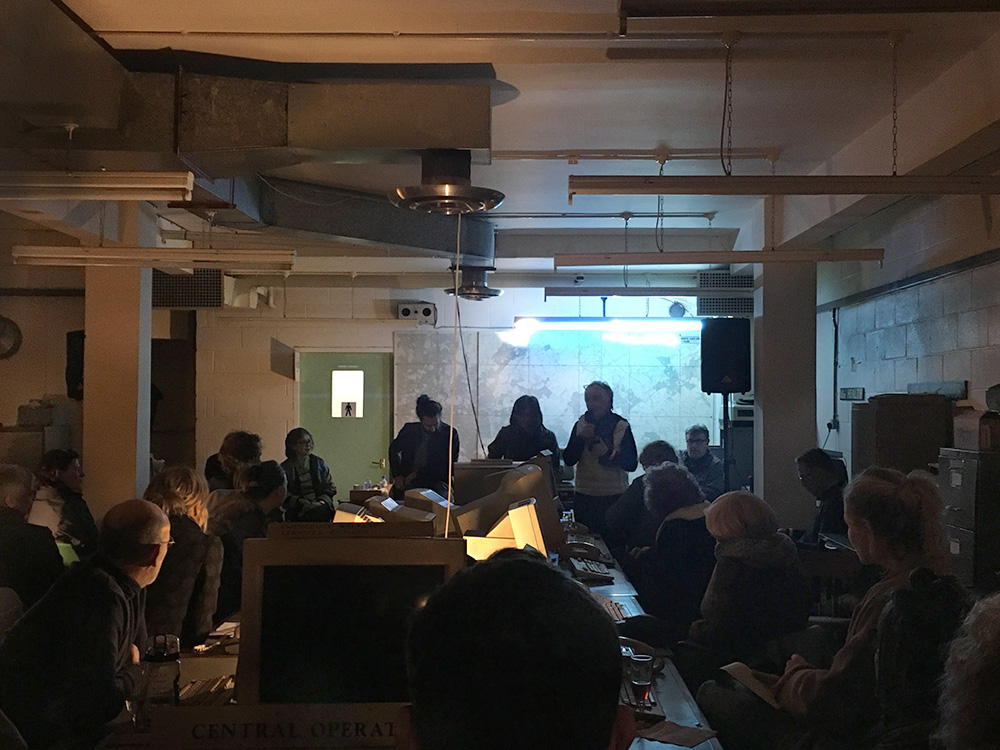

The panel, chaired by Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley, was part of the festival’s Nuclear Option day at the Kelvedon Hatch Secret Nuclear Bunker, a twisted network of dimly lit hallways and musty rooms that lie beneath a field.

Around 75 attendees gathered on March 25 to listen to Index’s panel and attend other workshops, screenings and performances part of the festival. Everyone at the festival was free to roam the enormous bunker and walk amongst Cold War history.

Passing signs that instructed people to “use water sparingly” and dusty machines that co-ordinated evacuation procedures, attendees eventually made their way to a desk-lamp lit room and were seated at long desks with old, monochrome computers.

Looking at the current state of propaganda, Bartlett said “everything has become more emotional and gut-driven,” adding that politics has not become as informed as people had hoped, but now become “heuristic because people are just showered with information”.

Aaronovitch called the inundation of information the “age of cacophony”.

What is emerging, according to Bartlett, is a “horrible new form of soft surveillance that has encouraged a great conformity among people”.

Xinran said China’s current propaganda, especially on social media, along with party control of education and the legal system has led to “one voice” in China, despite age gaps, class, education and geographical residence.

The author talked about her past experiences with censorship and Chinese propaganda when she worked on her radio show in China. She explained that there was a list of restrictions she had to abide by, these included never mentioning the British media, Western religions or love and relationships. The author said during her show she was able to tackle subjects that were previously taboos on Chinese radio.

“My work was stopped for three months when I spoke about homosexuality,” said Xinran. “This type of censorship was very strong until 1997, but it has now escalated to constant censorship, due to social media.”

Looking at the future of propaganda and its direction, Bartlett added that he can “see much more reliance on coercive digital types of surveillance being absolutely necessary just to maintain some type of law and order in society, especially online, which could make us a much more authoritarian society”.

This led Bartlett to predict that “already authoritarian countries are going to become much more so, and already very free countries are going to become even more free to the point where it might collapse”.

He believes we are shifting to a “Huxleyan society,” which Aaronovitch called the “algorithmic society”. Both felt one big question was, who governs the algorithms?

Aaronovitch noted that it depended on who was controlling the algorithms, saying that if the EU requested that Google to reveal its algorithms, it would be problematic; however, governmental algorithms used for policing in a democratic society were essential.

With reference to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which was mentioned numerous times during the panel, Bartlett noted that the worry over “Cambridge Analytica’s 5,000 data points on every single American doesn’t compare to what’s coming”.

“We are going to be creating a lot more data in the future,” said Bartlett. “And it is going to be shared and it is going to be used by political actors.”

Aaronovitch advised the audience that the best way to combat propaganda is to ask yourself, “‘Am I wrong?’. The point is to ensure no one is “completely blinded by initial preferences”.

Similar to Aaronovitch’s warning to predisposed biases, Xinran calls for “independent thinking,” and equated the consumption of information with eating.

“In Chinese we say you become what you eat,” said Xinran. “And your brain is the same way. You become what you are by what you believe”.

Love @EssexBookFest for concocting a 12-hour event in a secret nuclear bunker – blown away by the peace & propaganda panel with @IndexCensorship & a wild Gogol’s Silent Disco with gherkins & Estonian vodka! Will now be sleeping forever. pic.twitter.com/6B8kGwz5Uw

— Miranda Cichy (@mirazc) 25 March 2018

Hats off to @EssexBookFest! An incredible day at the Secret Nuclear Bunker. Brilliant discussion with @IndexCensorship, @JamieJBartlett, @DAaronovitch, @londoninsider and #Xinran, topped off with a silent disco of music banned from Estonia, with obligatory gherkins and vodka 👍 pic.twitter.com/HVtfrVDRb1 — Radical ESSEX (@RadicalEssex) 26 March 2018

So interesting to visit the secret bunker @khsnb @EssexBookFest today, fascinating @IndexCensorship session on propaganda pic.twitter.com/zY7EITOCfj — Namita E Chakrabarty (@DrNChakrabarty) 25 March 2018

Fantastic @EssexBookFest event at the Secret Nuclear Bunker with a timely discussion about propaganda @JamieJBartlett @DAaronovitch @londoninsider & Xinran. It was also a real privilege to hear Nicky Winder read her award-winning short story Bait – such a talent! — Sarah Roberts (@sarahrroberts) 25 March 2018

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522237614911-7109bbff-bdcf-1″ taxonomies=”2631″][/vc_column][/vc_row]