[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”99730″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]

“The noose is tightening around the Honduran people more than ever,” says Dana Frank, professor at UC Santa Cruz, specialising in human rights and US policy in post-coup Honduras, adding that with this comes increased repression of the media.

With political turmoil and protests following the 2017 re-election of president Juan Orlando Hernández, repression of information has become commonplace in Honduras. According to Amnesty International, at least 31 people were killed in the aftermath of the election, with hundreds more arrested or detained. Reporters Without Borders ranked Honduras 140th in the 2017 World Press Freedom Index.

Journalists reporting on corruption and violence in Honduras regularly deal with violence and the risk of death for their work — including investigative journalist Wendy Funes, a nominee for Index on Censorship’s 2018 Freedom of Expression Award for Journalism — while perpetrators often go unpunished.

“What’s amazing is that corruption is highly documented. For example, the government itself and the attorney general have confirmed the evidence that as much $90 million was stolen by the ruling party and the Juan Orlando campaign in 2013 from the national health service. They siphoned it into their campaigns,” says Frank. “The evidence of corruption is out there. The problem is that the attorney general and the government don’t act on the evidence.”

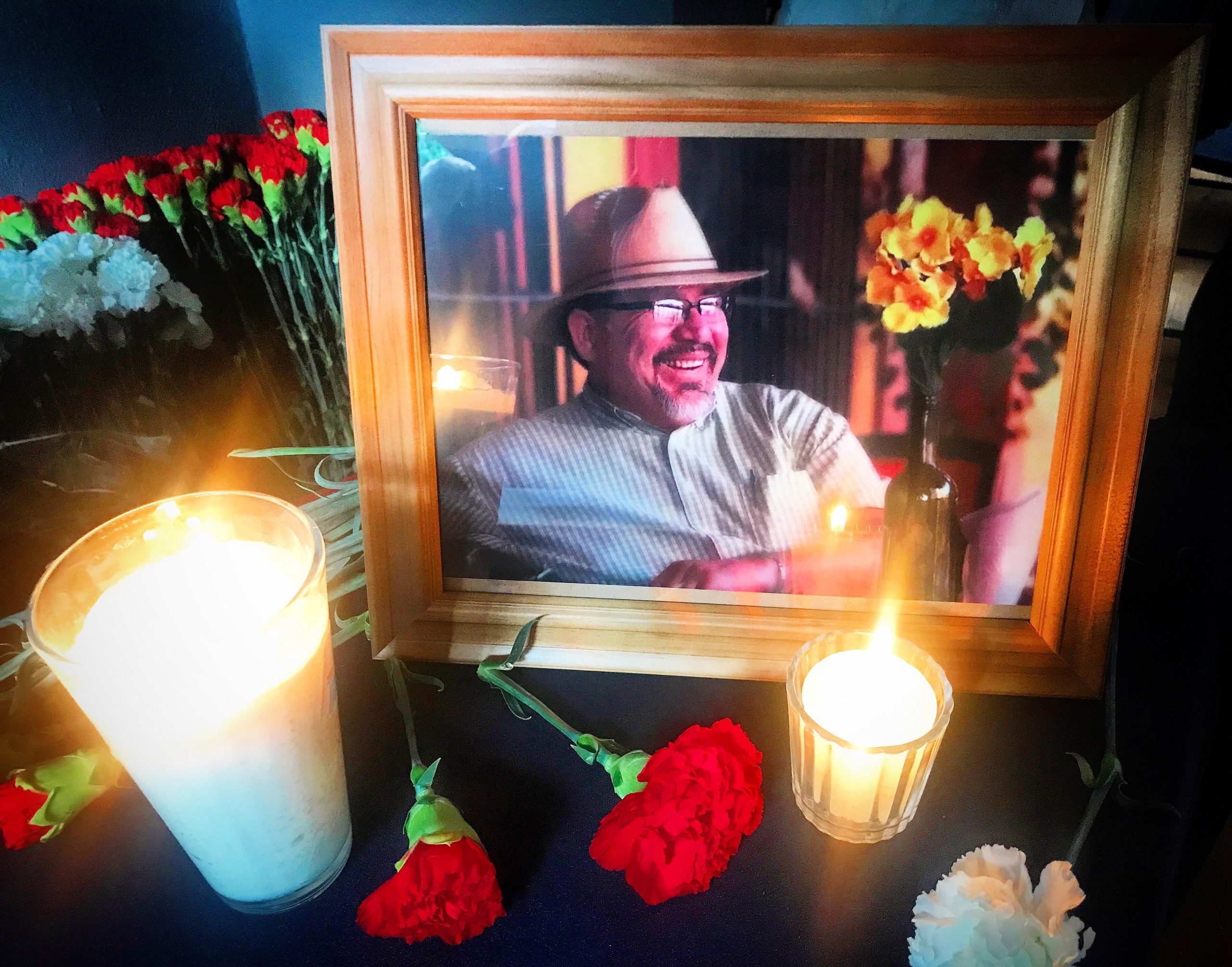

According to Honduras National Commission for Human Rights, over 70 journalists and other media workers were killed in Honduras between 2001 and August of 2017. PEN International reports that violence against journalists continued despite the Honduran government’s pledge at the United Nations in May 2015 to improve its human rights record. Journalists have begun to silence themselves out of fear for their lives.

“Over the years, the situation has been deteriorating and getting worse in regards to freedom of expression,” Honduran journalist Dina Meza told Index on Censorship in February 2018. “Therefore, what journalists and social communicators have started to do is self-censor.”

As recently as 13 February 2018, one Honduran television reporter, César Omar Silva, was the victim of an attempted on-air stabbing. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, Silva said that a nearby police officer and hospital worker told the man to stop but did not try to detain him or take his weapon. The attacker escaped.

This wasn’t the first time Silva was attacked for his work. He was kidnapped and tortured after he covered human rights violations around the 2009 coup.

Censorship by the government goes beyond attempting to silence journalists; it also restricts the information government agencies are allowed to release to the media and the public. A 2014 law assigned responsibility for releasing information to individual government agencies, instead of the more independent Institute for Public Access to Information. As a result, government transparency and the public’s right to information suffered.

“It really is a reign of terror. The government used live bullets against a labour strike on 9 March, and that’s new,” says Frank. “What’s amazing is that people are reclaiming democracy and going to the streets even though they know they could get killed.”

Frank echoed sentiments written by Dina Meza in a September 2013 article for Index on Censorship magazine. “In a democracy, criminal investigations would be the appropriate means to bring these culprits to justice,” said Meza, “but in what is an essentially failed state with a collapsed infrastructure, anyone who is determined to speak out risks their life.”

As journalists in Honduras face harsh censorship, those who continue to work and speak out must be supported and defended. Without this the corruption and repression in post-coup Honduras would go undocumented. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524040544190-383fec9d-ea6d-2″ taxonomies=”8996″][/vc_column][/vc_row]