[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

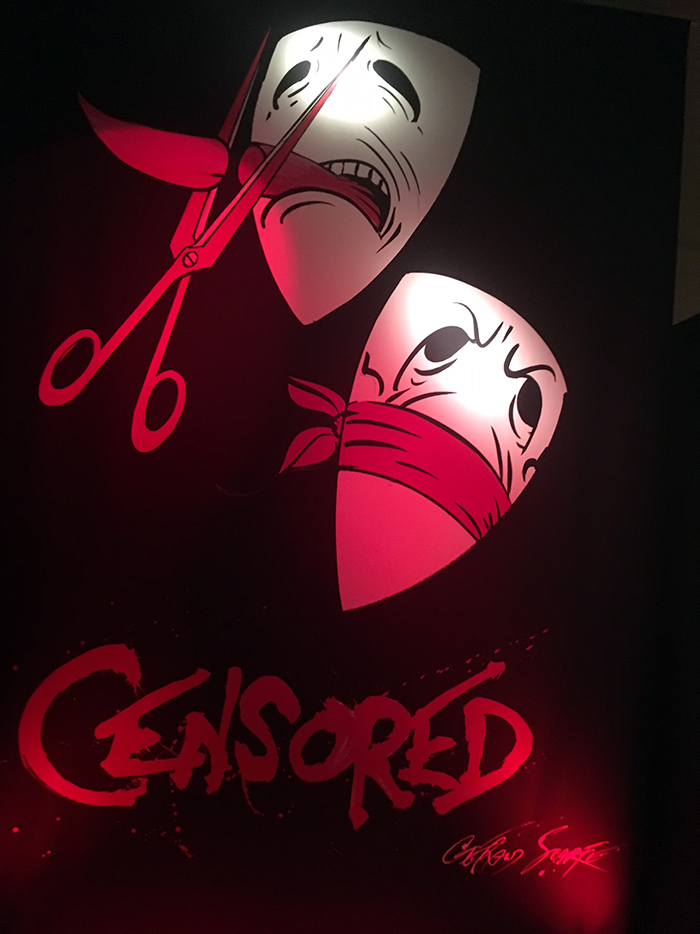

Censored by George Scarfe

Marking the 50th anniversary of the end of 300 years of theatre censorship, the Victoria and Albert Museum’s exhibition explores how restrictions on expression have changed.

The Theatres Act 1968 swept away the office of the Lord Chamberlain, which had the final say on what could appear on British stages.

“The 1968 Theatres Act was one of several landmark pieces of legislation in the 1960s, including the end of capital punishment, the legalisation of abortion, the introduction of pill, and the decriminalisation of homosexuality (for consenting males over the age of 21),” Harriet Reed, assistant curator at the V&A said.

Plays that had the potential to create immoral or anti-government feelings were banned by the Lord Chamberlain’s office or ordered to be edited. The exhibition includes original manuscripts with notes on what needs to be changed and letters from Lord Chamberlain explaining why the edits are required.

In the exhibition there are several pieces including a manuscript about the play Saved by Edward Bond. The play tells the story of a group of young people living in poverty and includes a scene in which a baby is stoned to death.

“When the Royal Court Theatre submitted the play to the censor, over 50 amendments were requested. Bond refused to cut two key scenes, stating ‘it was either the censor or me – and it was going to be the censor’. As a result, the play was banned,” Reed said.

Before the act was passed, playwrights got around the law by staging banned plays in “members clubs” which meant they could not be persecuted since it was private venue.

“The continued success of this strategy and the reluctance to prosecute made a mockery of the Lord Chamberlain’s powers and reflected the increasingly relaxed attitudes of the public towards ‘shocking’ material.

“The first night after the Act was introduced, the rock musical Hair opened on Shaftesbury Avenue in the West End. It featured drugs, anti-war messages and brief nudity, ushering in a new age of British theatre,” Reed said.

The exhibition changes from showcasing plays that were censored by the state to art, plays, movies, and music that are censored by society as a whole.

“It could be argued that a mixture of government intervention, funding/subsidy withdrawals, local authority and police intervention, self-censorship, and public protest now regulates what is seen on our stages,” she said.

Behzti, a play, and Exhibit B, a performance piece, were cancelled after protests by the public. The creators of both pieces were advised by the police to cancel their plays for health and safety reasons related to protests over the content.

Similarly, Homegrown, a play about radicalisation created by Muslims was shut down by the National Youth Theatre. The play was later published and a public reading was held.

On video, people involved in the UK arts industry such as Lyn Gardner, a theatre critic and Ian Christie, a film historian comment on what they believe to be censorship today. They cite art institutions that refuse to exhibit controversial material for fear of losing funding or facing public uproar. Julia Farrington, associate arts producer at Index on Censorship and one of the participants, calls this the “censorship of omission.”

The exhibition is capped by a piece by George Scarfe. The piece, the last work that attendees see, is a painting of two white masks on black cloth. The first one which is slightly higher and to the right of the second has it red tongue sticking out with the tip severed by a red scissors. The second one has a red cloth tied around it mouth. The word Censored is written in red and all caps below the two masks.

The painting is bold and the image of the tongue being cut off by scissors creates a “visceral” feeling. It depicts the two types of censorship that people now face– either talk and be violently censored or self-censor and never be heard.

“Many people would say that we are freer to express ourselves than ever before – with the boom of social media, we are able to communicate our thoughts and opinions on an unprecedented scale. This can also, however, invite more stringent and aggressive censorship from either the platform provider or under fear of criticism from other users,” Reed said.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

Artistic Freedom

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index encourages an environment in which artists and arts organisations can challenge the status quo, speak out on sensitive issues and tackle taboos.

Index currently runs workshops in the UK, publishes case studies about artistic censorship, and has produced guidance for artists on laws related to artistic freedom in England and Wales.

Learn more about our work defending artistic freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1534246236330-00e1ebeb-95f3-4″ taxonomies=”15469″][/vc_column][/vc_row]