Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=””][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

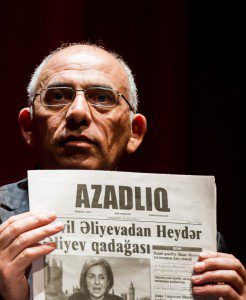

Rahim Haciyev, then acting editor-in-chief of Azerbaijani newspaper Azadliq in accpting the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Journalism Award in 2014 (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

On the night that Rahim Haciyev accepted the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Guardian Journalism Award, he held aloft a copy of the paper that persevered despite assaults from the government whose misdoings it exposed. It was March 2014 and Haciyev, acting editor-in-chief of independent Azerbaijani newspaper Azadliq, was on stage in London. Triumphantly, he declared: “The newspaper team is determined to continue this sacred job – serving the truth. Because this is the meaning of what we do and the meaning of our lives.”

Four months later, this mission was compromised by threats, arrests and financial constraints for reporting on government corruption. It was not the first time Azadliq experienced economic pressure from its government-backed distributors under Azerbaijan’s now four-term leader, Ilham Aliyev. Aliyev has long faced accusations of authoritarian rule and suppressing dissent since taking office in 2003.

But months of fines surpassing £50,000 and mounting arrests overwhelmed the paper, which suspended its print edition in July 2014. Among other members of civil society and the independent media, Haciyev’s colleague, columnist Seymur Hezi, remains imprisoned for “aggravated hooliganism” after defending himself from a physical assault. The public’s widespread protest went unheard by the government.

As of this year, Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index has documented that 165 journalists are currently imprisoned in Azerbaijan. Monthly, the Mapping Media Freedom database features reports on the former Soviet republic’s assault on dissenting speech. In July 2018 alone, MMF documented four opposition websites blocked by the government for spreading misinformation, two editors of independent news outlets questioned by authorities and one journalist arrested for disobeying the police.

In December 2017 a high court in Azerbaijan upheld the blockage of five independent media organisations’ websites, including Azadliq.info, active since March 2017. Haciyev criticised this move as further inhibiting the Azerbaijani people’s ability to access objective information.

Living in exile in western Europe since 2017, he told Index: “Four employees of our site are in prison. Our employees who are in prison were accused of hooliganism and illegal financial transactions. All of them were arrested on trumped-up charges. All the charges were fabricated.”

Haciyev oversees the paper’s Facebook page from abroad, while the website remains updated and accessible to readers outside Azerbaijan. Regarding the current status of free expression back home, he said: “The situation in the country is very difficult. The authorities continue to oppress democratically minded people. Arrests of political activists and journalists continue.”

Haciyev spoke with Index’s Shreya Parjan about the ongoing situation.

Index: Is Azadliq alone as a target? Why was the publication perceived as such a threat to the government?

Hajiyev: We can not say that only Azadliq was subjected to repression. Azerbaijani authorities are very corrupt and cannot tolerate criticism from their opponents. The corrupt and repressive regimes around the world suppress freedom of speech. In this regard, the Azerbaijani authorities, especially in recent years, have been in the ranks of the world’s most repressive.

Index: What ultimately made you decide to leave Azerbaijan and how difficult was the process?

Hajiyev: The newspaper ceased its operations in September 2012. The authorities have not allowed Azadliq to be published. At that time, they left the site of the newspaper. I stayed in the country for some time. I regret that I had to leave the country after the very strong pressure of the authorities. My colleague continued to lead the website and the Facebook page of the newspaper. Of course it is a difficult process. To be forced to leave the country [is a] very unpleasant affair. I had to endure a lot of trouble. Nevertheless, I continued the business.

Index: While in exile, how have you been able to continue your work and advocate for change?

Hajiyev: At this time in exile, I continue to guide the website and the Facebook page of the newspaper. Being outside the country, I actively use social networking. On the one hand, I gather information, on the other hand, I distribute it. Social networks help organise and conduct work. Our Facebook page is one of the most popular in the country, and I am proud of our achievement.

Index: Could you identify any supportive communities you have encountered with while in exile? What obligation do foreign journalists have to collaborate and support one another in times of crisis?

Hajiyev: Communication between journalists who are abroad is important. To share experiences and information would be useful. It would be very nice to be able to communicate work by local journalists.

Index: How does the crackdown on digital freedom oppose the government narrative of a modern, free Azerbaijan?

Hajiyev: In Azerbaijan, there is a political regime that strongly suppresses freedom of speech. According to the index of freedom of speech, composed Reporters Without Borders, Azerbaijan occupies the 163rd place. Azerbaijan is currently undergoing one of the most difficult times in its history. The rights and freedoms of citizens have long been of nominal character. There are now more than 160 political prisoners.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Global Journalist / Project Exile” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

İdris Sayılgan’s father Ramazan, mother Sebiha and sisters Tuğba and İrem pose in the meadow where the family comes the summers to breed their cattle (Credit: Özgün Özçer)

“Don’t forget to take pills for nausea,” says İdris Sayılgan’s younger sister, Tuğba, combining her knowledge as a fifth-year pharmacy student and the innate kindness of a host. Together with a colleague, we were about to take the bumpy road to follow in the jailed Kurdish journalist’s footsteps to his family’s village near the eastern Turkish city of Muş. Sayılgan had spent his summer holidays helping his father, a herdsman or “koçer” in Kurdish (literally meaning “nomad”), breeding cattle and goats. One of many Kurdish reporters imprisoned pending trial, Sayılgan has been behind bars for 21 months on trumped-up charges that have criminalised his journalistic work. His hard-working, close-knit family misses his presence dearly.

Heading south of Muş, to the fertile Zoveser mountains, the serpentine road proves Tuğba’s advice to be valuable. The asphalt pavement gives way to a narrow gravel road as we continue to zig-zag toward the southern flank of Zoveser, bordering Kulp in Diyarbakır province and Sason in Batman – two localities which used to be home to an important Armenian community before the Armenian Genocide in 1915. The many majestic walnut trees surrounding the road are a testament to that bygone era. We are told that they were all planted by Armenians before they fled.

The family village – Heteng to Kurds and İnardi to the Turkish state – witnessed another brutal eviction in more recent times. During the so-called dirty war of the 1990s, the Turkish military gave inhabitants a stark choice: either become village guards, armed and remunerated by the state to inform on the activities of militants belonging to the Kurdish insurrection, or leave. If they dared to refuse, a summary death awaited. İdris was just three-years-old when they came.

Left helpless and scared, many left. The family of Çağdaş Erdoğan, the Turkish photographer hotlisted by the British Journal of Photography who recently spent six months in prison on terror-related charges, was among them. Erdoğan scarcely remembers his childhood before his family moved to the western industrial city of Bursa. As a child, the painfully forced exile produced nightmares. He started imagining stories from patches of memories, believing they were real. Zoveser’s idyllic setting is haunted by the ghosts of a dark history brimming with atrocities.

The family guides the cattle to the pasture. (Credit: Özgün Özçer)

As for İdris’ family, they have stayed in the Muş ever since, coming back only for breeding season. İdris used to accompany his father in guiding their cattle, during which time they would cover the 70 kilometres separating their farm near Muş to Heteng in three days. It’s a distance that we could only cover in two-and-a-half hours by vehicle. Once in Heteng, there’s still another 15 minutes on foot to the small meadow where the Sayılgans have set up camp next to a fresh stream.

İdris’ father, Ramazan Sayılgan, greets us with a warm embrace. He has a gentle look with soft and tired eyes. “Are you hungry?” he asks as we are invited to their tent. His wife, Sebiha, brings us milk and fresh kaymak cheese, a cream obtained from yoghurt, that she made herself, as well as milk. All of the children help the family during the breeding season. Ramazan can’t hide his pride when he recounts how well they are doing in their studies and how gifted they are. Unlike many parents in the region, he strived to send his nine children to school despite his meagre income. The nine brothers and sisters are close and often go the extra mile for each other.

İdris is the very picture of his father who, although sunburnt, is a little bit darker than him. He inherited the whiteness of his skin from his mother, whom he calls “the most beautiful woman on earth.” With them are the five youngest of the family. Involving herself in the conversation, eight-year-old Hivda sadly notices that she is the only one with olive skin, like her father. Ramazan Sayılgan is quick to comfort her. “You may be darker but you are such a beautiful, dark-skinned girl.” Hivda giggles cheerfully.

They work together and laugh together, but they also suffer together – like that fateful day when the police came for İdris.

A rifle to the head

It was early in the morning on 17 October, 2016, long before sunrise. The whole house was soundly asleep when their door was broken and ten riot police stormed inside.

“They were screaming ‘police, police!’ I told them: ‘Please be quiet, there is nothing in our house,’” Ramazan Sayılgan says, occasionally mixing Kurdish with his broken Turkish. “I was trying to calm them down and avoid trouble. Then I raised my head and saw that five people were on İdris. That’s when they kicked me in the head.”

İdris Sayılgan’s eight-year-old sister Hivda and 12-year-old Yunus. The family guides the cattle to the pasture. (Credit: Özgün Özçer)

İdris tried to escape their clutches but fell to the floor. Police kicked him repeatedly while threatening him. The blows had left him bleeding. “They are killing İdris!” cried his sister İrem, who was 12 at the time. Police told the family to lie on the ground with their hands on their backs. They pointed a rifle at Ramazan and one of the journalist’s younger brothers, Yunus. “They even pointed two rifles at my head. They have no shame,” Yunus, who was ten-years-old at the time of the raid, says.

Normally, all raids should be filmed as a means of preventing abuse. “But they only started filming after they inflicted their brutality,” Ramazansays. Those who inflicted the beatings have enjoyed complete impunity. The family even saw the commander, a bald officer, when they went to vote during Turkey’s recent presidential elections.

In a written defence submitted to the court, İdris said that when he was brought to the hospital for a mandatory medical examination, doctors effectively turned a blind eye to police brutality by refusing to treat his injuries out of fear of repercussions from the police. To add insult to some very real injuries, İdris was transferred to a prison in Trabzon, some 500 kilometres north on the Black Sea coast, even though there is a prison in Muş. The family, who cannot afford a car, can only visit İdris on rare occasions. İdris was subjected to torture and strip searches after being transferred to Trabzon, where he is held in solitary confinement. “What I have been through is enough to prove that my detention is politically motivated,” the journalist has said in his defence statements.

“Journalism changed him”

After high school, İdris decided to abruptly end his studies and began working as a dishwasher. That, however, only lasted three months before he announced to his father that he wanted to prepare for the national university exams. “When he sets his mind on something, he always tries to do his best. He never puts it off. Nothing feels like it’s too much work for him,” his father tells us. “He didn’t study at first, but when he decided to do so, he devoted himself.”

İdris graduated from the journalism department at the Communication Faculty at the University of Mersin. He then returned to Muş and started to work for the pro-Kurdish Dicle News Agency (DİHA), which today operates under the name Mezopotamya Agency after DİHA was shuttered in 2016, and another iteration, Dihaber, in 2017, both on terror-related allegations. İdris was making a name for himself when he was arrested and now faces between seven-and-a-half and 15 years in prison on the charge of “membership in a terrorist organisation”.

“University and journalism changed him,” 18-year-old İsmail says. “He used to be more irritable. He has been much more cheerful since,” says İsmail, who picked up on his brother’s habit of whistling whenever he comes home. “İdris was even whistling in custody – to the extent that the police asked, ‘How can you remain so upbeat?’”

Sebihan Sayılgan, İdris’ mother, who he calls “the most beautiful woman on earth”. (Credit: Özgün Özçer)

Tuğba remembers endless conversations at nights when İdris would recite poems by Ahmed Arif, a poet from Diyarbakır who was partly Kurdish. Yunus, meanwhile, complains that he only received İdris’ latest letter a full six weeks after it was sent. As for little Hivda, she whispers to us that she just sent him a poem she wrote.

Ramazan adds that İdris is loved by everyone who knows him. At 58, Ramazan continues to work hard but the family faces many adversities. Another son, 21-year-old Mehmet, has also been behind bars for two years. The eldest brother, Ebubekir, who became a math teacher, has been dismissed from the civil service for being a member of the progressive teachers’ union Eğitim-Sen. Ebubekir was well-known for improving the grades of all the students in his classes, but now that he has been forced out of his job, he has gone to Istanbul in an attempt to make ends meet. He will join them a week later to help them during the breeding season.

Since the state of emergency was imposed two years ago, village guards have become ever more self-assured. Like sheriffs in the wild west, they make their own rules. The Sayılgan family, who couldn’t come to the village for two years out of fear following the declaration of a state of emergency, alerts us that village guards often tip off authorities when they see strangers. “The driver of the shuttle is also a village guard,” we are warned. Indeed, we had already introduced ourselves to him as İdris’ friends from university, omitting to reveal our profession. During our trip back, we would tell him of our plans to catch a bus to Van when our real intention was to go north to Varto instead.

İdris Sayılgan’s 18-year-old İsmail who guided us to the meadow, with Hivda and Yunus in the background. (Credit: Özgün Özçer)

Unlike most Kurdish provinces, the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), well supported by the conservative voters, won the municipality of Muş in local elections, meaning the government hasn’t appointed trustees to force out elected Kurdish mayors as it has done in other Kurdish areas where it has lost. Police, accordingly, are extremely comfortable. The city abounds with plainclothes police and informants. No precaution is too little. Varto, a town with a majority of Alevis – who are a dissident religious minority with liberal and progressive beliefs – looks like a safer option to spend the night.

I get a sense of how hard it must be for a local Kurdish reporter to work in Muş. It means working behind the adversary’s lines while still living in one’s hometown. It also means never letting your guard down.

We take leave from the family, expressing our hope that İdris will be released at his next hearing on 5 October. “In three months and two days,” his father quickly notes. October will mark two years without his son – two years that a modest but resilient family has endeavoured to fight against state-sponsored injustice with goodwill and affection.

İdris Sayılgan’s father Ramazan, mother Sebiha and sisters Tuğba and İrem pose next to the tent where the family stays. (Credit: Özgün Özçer)

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1532352402886-c28cce4d-6f18-8″ taxonomies=”1765, 1743″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Activist Amal Fathy has been ordered detained. (Photo: Facebook)

Egyptian activist Amal Fathy, who was arrested on 11 May after posting a video criticising sexual harassment in Egypt – of which she herself is a victim – to Facebook, appeared in court on 15 July only to have her hearing for a fourth time by 15 days.

Fathy has been in pre-trial detention since her arrested after publishing the 12-minute video on 9 May, during which time she has shown symptoms of acute stress and was unable to walk unassisted at her 4 July trial, having lost sensation in her left leg. Fathy has a history of chronic depression, bipolar disorder and anxiety, conditions that have only worsened during her detention.

“Egypt is inciting fear on their population by limiting a fundamental human right, which includes the persecution of activists like Amal,” said Perla Hinojosa, fellowships and advocacy officer at Index on Censorship. “Index is also deeply concerned by a new bill that will allow further monitoring of social media accounts, which will make even more difficult for outspoken activists.”

Fathy, along with her husband, Mohamed Lotfy, director of the Index award-winning NGO Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms, and their son, were taken into custody during an early morning raid on their home. As an activist, Fathy has also been vocal about human rights violations in Egypt, especially the arbitrary detention of other activists. Lotfy and their son – who Fathy was the primary carer of before her arrest – were later released.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1532012897356-010363ff-19af-10″ taxonomies=”147″][/vc_column][/vc_row]