Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

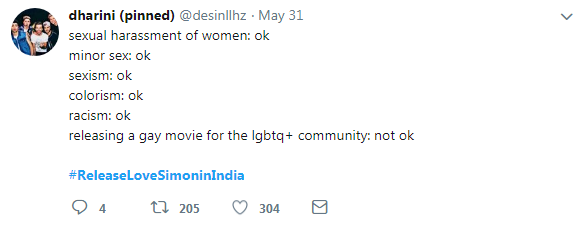

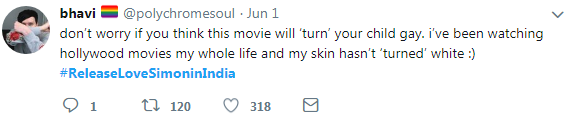

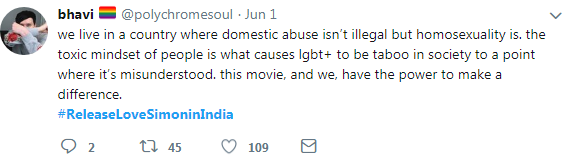

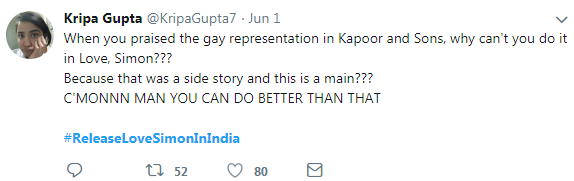

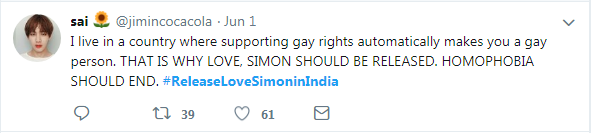

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”101140″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Indians took to Twitter to express their frustration after the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) pushed the release of the film Love, Simon back indefinitely.

Originally slated to be released on 1 June, Love, Simon was eagerly awaited by some Indian moviegoers, who attempted to purchase advance tickets only to be denied. Soon after the hashtag #ReleaseLoveSimoninIndia began trending.

Love, Simon is a film based on the book Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda written by Becky Albertalli in 2015. Simon is a 17-year old boy in high school who despite having close, loving and supportive relationships with his friends and family keeps his homosexual identity a secret from them. This is the first major gay romantic comedy film to be released by a major US studio. Fox 2000 rolled it out in the US, where the movie had a favourable response from both critics and movie-goers.

According to an anonymous source cited by The Free Press India, the CBFC decided against allowing the film to be shown because there is “no audience” for it. This assertion flies in the face of the film’s worldwide success and vocal supporters within India.

“I doubt that it can be said that the film has “no interest” but rather it has less popularity than other mainstream foreign movies, the reason being India is deeply homophobic but I don’t think that justifies not releasing it,” Ruth Chawngthu, the digital editor at Feminism in India and co-founder of Nazariya LGBT, told Index on Censorship via email. “I could be wrong but to my knowledge the film creators decided to not release it so perhaps the concerned persons should petition them instead? I personally don’t have strong feelings regarding the issue because it’s mostly the privileged upper class who are concerned about it. They were focused on the movie while ignoring the fact that members of the LGBT community were facing violence in different parts of the country at the same time.”

The CBFC states that it stands in the way of “[moral] corruption [as social depravity] has been one of the major obstacles to economic, political and social progress of [India].” This is in relation to Penal Code 377, a leftover from the Victorian era when India was a part of the British empire, and has yet to be changed due to social anxiety around the LBGT+ community. While India is in the process of reconsidering its 377 Penal Code which criminalizes “unnatural relations with man, women, and animal”, the diverse traditional religious communities within India and social stigma hold back public opinion.

Indians took to Twitter to express their opinions on the indefinite delay on Love, Simon’s release: [/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Politicians such as Rajya Sabha MP and BJP leader Subramanian Swamy feel justified in delaying the release of the film to “protect the culture of India”. Twitter users raved that Love, Simon would have been a landmark film that would humanize the LBGT+ community in India. However, at the tail end of International Pride Month, the film has still yet to be released. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Politicians such as Rajya Sabha MP and BJP leader Subramanian Swamy feel justified in delaying the release of the film to “protect the culture of India”. Twitter users raved that Love, Simon would have been a landmark film that would humanize the LBGT+ community in India. However, at the tail end of International Pride Month, the film has still yet to be released. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=””][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Recep Tayyip Erdogan has won Turkey‘s presidential election for the second time. His victory will mean he has a tighter hold of his country. What was the result of the election? With a high voter turnout of 87 per cent, Mr Erdogan hailed victory in the presidential poll on Sunday. He managed to overcome what many considered was an opposition party that had been gaining momentum. Read in full.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This article is part of Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist’s Project Exile series, which has published interviews with exiled journalists from around the world.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”101034″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Jumping out of a car to escape being abducted at gunpoint by the Pakistani military isn’t exactly how journalist Taha Siddiqui planned to start his trip to London.

Siddiqui, then a Pakistan correspondent for the network France 24 and the Indian news site WION, had angered the South Asian nation’s military with his reporting on national security issues and critical posts on social media.

On 10 January the problems caught up with him as he rode to the airport in a Careem, a popular ride-hailing service in the capital Islamabad. A car with armed men in it forced Siddiqui’s driver to stop. He was beaten by the side of the highway and the men forced him into the back of a vehicle and started to drive off with him.

Pakistani media is noted for its lively and diverse news coverage. Yet reporters in the country face threats not just from extremist groups like the Taliban but from the military and intelligence agencies.

The country ranks 139th out of 180 countries on Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index, and in recent months independent media like Geo TV and Dawn newspaper have been blocked from distribution. Earlier this month two reporters were attacked in Lahore shortly after a military spokesman condemned “anti-state” remarks made by journalists on social media.

As Siddiqui told Global Journalist, he was able to escape from his captors and report the attack to the police. The kidnapping attempt wasn’t the first time Siddiqui had problems with Pakistan’s military. In 2015, he was threatened after he co-wrote a lengthy New York Times article detailing how the military had disappeared dozens of suspected Pakistani Taliban members. The article included allegations that some of those disappeared were starved, tortured and killed.

He was also threatened after helping produce a France 24 report critical of the Pakistani army’s handling of a 2014 school massacre in Peshawar that left over 150 dead. Siddiqui had also faced pressure last year after posting tweets critical of the military’s “glorifying” of past dictators and its whitewashing of its role in fomenting a 1965 war with India.

Pakistan Army media wing should stop glorifying dictators of past… https://t.co/GqMaaa1vLW

— Taha Siddiqui (@TahaSSiddiqui) August 25, 2017

In May 2017 he was summoned for questioning by the federal police’s counter-terrorism department despite a court order banning them from harassing him. In September, Siddiqui was called to meet with the military’s spokesman, Gen. Asif Ghafoor. In an interview, Siddiqui says Ghafoor told him that if he didn’t stop his criticism, “I would get myself into trouble.”

Ghafoor did not respond to messages seeking comment from Global Journalist. Yet trouble didn’t come until the January attack, and Siddiqui can’t point to one specific incident as a cause.

“I don’t know what specific story, article or video triggered it,” he says in an interview with Global Journalist. “Or was it just my social media activity?”

Weeks after the attack, Siddiqui, decided to leave Pakistan for France for security reasons. Before he left, he says he met with Pakistan’s then interior minister, Ahsan Iqbal. Iqbal, Siddiqui says, told the journalist he should write a letter to Gen. Qamar Bajwa, Pakistan’s army chief, and beg for forgiveness. Neither Iqbal nor Bajwa responded to requests for comment.

Now 34, Siddiqui lives with his wife and 4-year-old son in Paris, where he is working part-time with the media company Babel Press and looking for a full-time job. He spoke with Global Journalist’s Rosemary Belson about his attack and flight from his homeland.

Global Journalist: Can you tell us about the reporting that landed you in hot water?

Siddiqui: The military is politically-involved in Pakistan. They have businesses, they are involved in human rights abuses, education.

When reporting in Pakistan about any particular issue, usually you end up tracking it back to the military in some way or another. It’s impossible to report without talking about the military and its involvement in a wide range of issues in Pakistan.

I refer to a story that I did for the New York Times. It came out on the front page of the International New York Times in 2015. It was a story about military secret prisons where they were killing suspected militants. They were extrajudicially killing them inside the jails. I uncovered about 100 to 250 cases across Pakistan, especially in the Tribal Belt [in northwest Pakistan].

Even at that time, the New York Times thought it was quite risky for my name to go on it. But I wanted my byline on it and that was the first time I started receiving direct threats.

There were always indirect messages coming in through friends in the journalism business or friends in the government saying that I should be careful… Constantly on and off these threats would come. Even to the extent where my friends and people I socialized with were told to stay away from me.

GJ: Walk us through the attempted abduction.

Siddiqui: On 10 January I was headed to the airport to catch a flight to London for work. The week before that I was working on a story about missing persons. I was supposed to file the story from the airport because I didn’t have [time] to file it before, so I took [my] hard drive and laptop.

My Careem came around 8 a.m. for my flight at noon. Halfway to the airport on the main Islamabad highway, a car swerved in front of me and stopped. Armed men got out of the vehicle with pistols and AK-47s.

At first, I thought it was a case of road rage or robbery, but one of them approached from my side and pointed his gun towards me and said something along the lines of: “Who do you think you are?”

I got out and assumed that this had something to do with the threats I had been receiving. I tried to run away but they pinned me down on the road. That’s when I noticed there was another car behind me with people coming out of it as well. They made a barricade around me, and this was [on] the main highway at 8:30 in the morning, with traffic…they started beating me and wanted to take me away.

I was resisting and they kept hitting me with the butts of their guns…and kicking me. Finally, one of them said, “Shoot him in the leg if he doesn’t stop resisting because we have to take him.”

That’s when I realized they were serious about shooting me. Earlier, [when] they didn’t shoot me right away, I thought perhaps it means they want to take me alive. In my mind I was thinking that resistance would give me some lifeline. I saw a military vehicle passing by. I called out for help but it didn’t stop.

After being threatened by being shot in the leg, they put me in the taxi, and took out the driver. One person drove while two people sat with me in the back and one in the front. They were holding me in a headlock with a gun pointing to the left side of my body on my stomach.

I told him, “I’m going with you. Can you relax for a little bit and let me relax also, [and] sit up straight?”

The guy relaxed his arm and gun. That’s when I realized the right back door of the car was unlocked. I went for it, opened it. I jumped out, ran to the other side of the road with oncoming traffic. I tried to look for a taxi. I could hear behind me they were shouting and saying, “Shoot him!”

But I just ran and finally I found a taxi. I got into it while it was moving. I opened the door, jumped into it. The taxi took me 700 or 800 meters before realizing there was something wrong and [the driver] didn’t want to help me anymore. So they asked me to get out because it was already occupied by some women.

This is Taha Siddiqui (@TahaSSiddiqui) using Cyrils a/c. I was on my way to airport today at 8:20am whn 10-12 armed men stopped my cab & forcibly tried to abduct me. I managed to escape. Safe and with police now. Looking for support in any way possible #StopEnforcedDisappearances

— cyril almeida (@cyalm) January 10, 2018

I got out of the taxi. On the side of the road, there were some ditches and a marsh area, so I jumped into that and hid there for a bit. I took off my red sweater because I was worried they’d see me…we later recovered the sweater with the police.

I found another taxi. I asked to use [the driver’s] phone. I called a journalist friend and asked him what to do. He suggested I go to the nearest police station and the taxi driver took me. I filed a report where I named the Pakistan military as a suspect. I also tweeted about it from a friend’s account because they had taken my phone, passport, suitcase, laptop, bag. I only had my wallet left on me.

GJ: How did you make the decision to leave Pakistan?

Siddiqui: The police investigation found that the [surveillance] cameras in the area weren’t working. They found one of the cars that stopped me was following me from my house but they couldn’t identify any of the faces inside the car because [the windows] were tinted and the license plate was fake.

I was invited [to a meeting] by the Interior Minister of Pakistan [Ahsan Iqbal]. He suggested that I should write a letter to the Pakistan Army Chief [Gen. Qamar Bajwa]. That’s when I realized the government was totally helpless.

People suggested that I go away for awhile because they didn’t finish the job and they might come again. Especially since I wasn’t going silent, as was suggested by some senior journalist friends who later turned their back to me during this ordeal.

It was really disappointing and depressing seeing my own journalist community not supporting me. The international media supported me, some local journalists supported me, but some people that I knew personally thought I was going the wrong way by being vocal about the attack.

Me, my wife…we sat down together and discussed. We didn’t tell my kid at the time but now I’ve gently told him how there’s a safety issue for me and we had to move.

We decided that we should get out. If we are getting out, it wasn’t going to be a three or six-month thing, because I’m fighting invisible forces in my country. I will not know if I’ve won or lost or whether they’re still after me or not.

We decided on Paris because I had been working with the French media for the last seven or eight years as a journalist for France 24. I also received the French equivalent of the Pulitzer prize [the Albert Londres prize] in 2014, so I have strong journalistic support and community here.

GJ: How has media freedom changed over time in Pakistan?

Siddiqui: Press freedom has always been under attack. We’ve gone through military dictatorships in Pakistan…through the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

Two things have changed in recent years. One, we as journalists don’t know what the red lines are. In my case, I don’t know what specific story, article or video triggered it. Or was it just my social media activity?

Secondly, non-state actors are now being activated against journalists so [the military] can hide behind those non-state actors and get the job done.

The military has ensured that unity among journalists is not as it used to be. They have done that through financial coercion or financial rewards…it’s further shrunk the space for journalists. The military is becoming more intolerant and its tactics to control the media are becoming more violent. I see the situation becoming worse in the coming days.

This all needs to be put in context. It’s an election year in Pakistan. The Pakistani military wants all of this room to manipulate elections for strategic gains. They don’t want the ruling party [Pakistan Muslim League – Nawaz] to come into power again with a similar majority to what they enjoy right now. So to make sure they can easily manipulate the elections, they are trying to develop an environment of fear where independent reporting can’t happen.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/6BIZ7b0m-08″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook). We’ll send you our weekly newsletter, our monthly events update and periodic updates about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share, sell or transfer your personal information to anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Global Journalist / Project Exile” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]