[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Forty years ago, on 11 February 1979, the rule of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last shah of Iran, came to an end after millions of Iranians, from all backgrounds, took to the streets in protest at what they saw as an authoritarian, oppressive and lavish reign.

After decades of royal rule, and following 10 days of open revolt since the return of Ayatollah Khomeini to the country after 14 years of exile, Iran’s military stood down. With Pahlavi forced to leave the country, the Islamic Republic of Iran was declared in April 1979.

Here Index on Censorship magazine highlights key articles from its archives from before, during and after the revolution, an event that has since shaped the entire Middle East and has had a lasting impact to this day.

Repression in Iran , the Winter 1974 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Ahmad Faroughy

December 1974, vol. 3, issue 4

In October 1972, the shah of Iran celebrated the 2,500th year of Persian Monarchy which, despite twenty national dynastic changes, has constantly endeavoured to remain Absolute. Although the aim of this article is not to debate the political merits and demerits of autocracy as a means of government, it is obvious that whatever minor benefits Iran may have derived from hereditary dictatorship, freedom of expression is certainly not one of them.

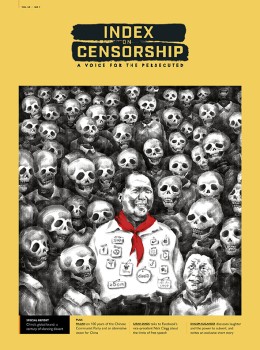

China: Unofficial texts, the September 1979 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

M. Siamand

September 1979, vol. 8, issue 5

The Muslim clerical establishment had not been decimated, and the various peoples of Iran, showing a remarkable unanimity, rallied behind the exiled Ayatollah to overwhelm the imperial army into submission by staring it In the face. What the great majority of observers regarded as impossible has come to be: the minority cultures seem no longer in danger of quick extinction, and everyone is engaged in an exhilarating debate about the future. But unfortunately, threatening clouds can be seen gathering on the horizon. The revolution has not yet started to devour its own children, yet some powerful men in the new hierarchy are already saying that it might have to do so: secular, democratic opponents of the former regime are denounced as counter-revolutionaries, most clergymen seem determined to turn Iran into an intolerant theocracy and a cultural backwater, and martyrdom for Islam is held up for the young as the highest achievement they should aim at.

The rebirth of Chilean cinema in exile, the April 1980 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Edward Mortimer

April 1980, vol. 9, issue 2

An extraordinary exhilaration gripped the Iranian people as the revolution at last triumphed and the remnants of the imperial regime suddenly crumbled away. One returns to confront the irritation of a European intelligentsia which is at once alarmed by the possible consequences of the Iranian revolution and perplexed by the fact that it does not quite fit into any of the ideological pigeon-holes which Western thought had prepared for it; and one is expected to atone by taking responsibility for the events which follow it.

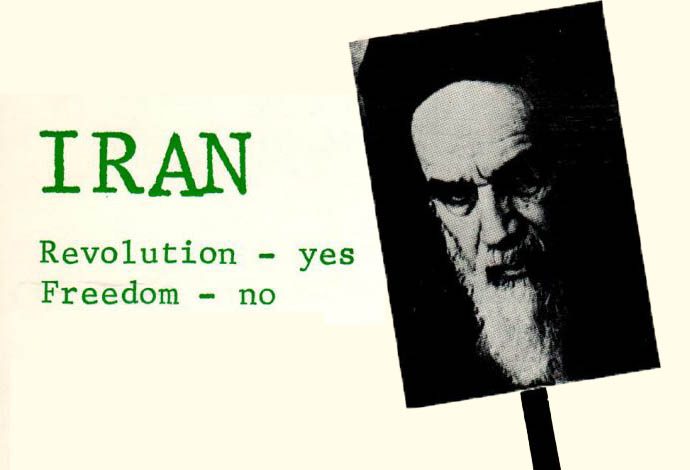

Iran: Revolution – yes, Freedom – no, the June 1981 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Leila Saeed

June 1981, vol. 10, issue 3

Concern for the restoration of social justice, for basic human rights, as well as national independence, provided the fundamental motive for the formidable mass movement which brought down the Pahlavi dynasty in February 1979. Iranians of different social backgrounds, ethnic and religious groups, of different creeds and ideologies came together in their revolt against the oppressive and arbitrary regime. And it was religion which provided the formal channels and the leadership by means of which the opposition expressed its demands and conducted its struggle.

Writers and Apartheid, the June 1983 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

The Islamic attack on Iranian culture

Amir Taheri

June 1983, vol. 12, issue 3

Book-burning did not become an Islamic tradition. On the contrary. The Bedouin’s enchantment in front of the written word soon prevailed over the Caliph’s ‘ impulsive outburst. Islam expanded and developed into an established religion with universal appeal, and became an accidental heir to the wisdom of the classical world which it later passed on to the West. In 1979, in the triumph of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, an echo of Omar was heard. In their hatred of the “corrupt” contemporary world, Iran’s mullahs, who had designed and led the revolution, tried to “return to the source” and recreate the early Islamic society as they imagined it. An important step in that direction was what the revolution’s Supreme Guide, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, described as “deculturisation”.

Samuel Beckett: Catastrophe, the January 1984 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Gholam Hoseyn Sa’edi

February 1984, vol. 13, issue 1

Censorship was planned by the regime of the Islamic Republic even before the February 1979 revolution brought Ayatollah Khomeini’s theocratic oligarchy to power. This particular kind of censorship may not be without precedent in history, but it must certainly be rare. There were attacks on coffee-houses, restaurants and other public places by men armed with clubs and stones; unveiled women were harassed; slogans of the opposition were cleaned from the walls; banks, cinemas and theatres were burned. None of this seemed to follow any specific plan, but nonetheless it just kept on happening. Men with angry faces, dressed in shabby clothes, would be seen lurking in corners; they would come out for a moment of sudden violence and then disappear again. An astute observer might have called those attacks wounds on the body of the revolution as it was in the process of taking shape, but not many people noticed, and consequently they saw this deranged behaviour simply as a sign of revolutionary anger and class hatred.

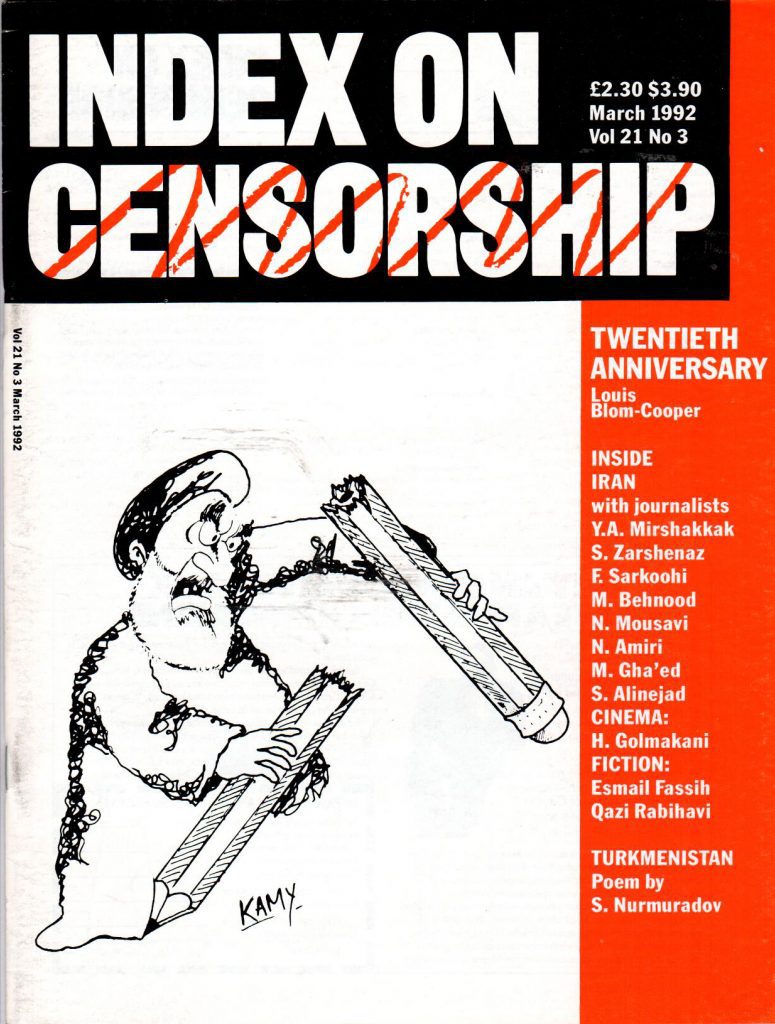

20th Anniversary: Freedom and responsibility, the March 1992 issue of the Index on Censorship magazine.

Gholam Hoseyn Sa’edi

March 1992, vol. 21, issue 3

Index brings together opposing views on the nature of human rights, freedom of expression and democracy within the Islamic Republic of Iran. This unique confrontation, first presented on 14 December 1991 on the UK’s independent Channel 4 TV programme South, reveals the gulf that separates the ‘universal’ principles of the Western Christian/humanist tradition from the theocentric teachings of Islam on the same matters. Even within Iran, the battle between rival and opposing interpretations of Koranic teaching on these subjects reaches into the highest levels of government.

As the Iranian journalist Enayat Azadeh, intimately connected with the film, himself says, we are not talking about anything as simple as those who are for and those who are against the Revolution. Committed supporters of the Islamic state who, influenced by education and inclination, wish to incorporate Western liberal ideas into Islamic thinking on, for instance, freedom of expression in the media or the arts, find themselves at odds with the pure Islamists who will brook no interference with the integrity of Islam

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1549892591542-afaf5ec8-5514-0″ taxonomies=”8890″][/vc_column][/vc_row]