[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”107744″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]It could be argued that identity has become a dominant feature in contemporary art and performance since the 1980s, where artists have been and still are exploring the multiple worlds they inhabit, the overlaps between identity, language, history, geopolitics, race and representation. The characteristics of identity as represented in folk or popular culture and the media are interrogated through performance and the semiotics of how identity is enacted. A particular controversial trope in performance has been that of the “blackface”. Wikipedia’s entry describes blackface as a form of “theatrical make-up used predominantly by non-black performers to represent a caricature of a black person”. Undoubtedly the grotesquery and exaggeration contributed to justifying the dehumanising of Africans and other non-white people by the dominant white masters in slavery and colonialism, and popular culture shows such as The Black and White Minstrel Show.

Recently “blackfacing” has been highlighted in many cultural manifestations that may not necessarily have been intended to demean Black or other non-white people. In January 2019, The film Mary Poppins was accused by a writer in the New York Times of shamelessly flirting with blackface, and an American restaurant displaying a photograph of white coal miners covered in coal-soot was seen as offensive by Rashaad Thomas in his opinion piece for azcentral, the digital home of The Arizona Republic newspaper, in February 2019.

Viewing blackfacing through the lens of racial subordination/superiority struck me again this year when I met and mentored the Warwickshire based British visual artist Faye Claridge this year for Bloomberg New Contemporaries. Claridge’s work reveals a deep fascination with “representation and belonging in a country obsessed with (constantly reworked) history” by exploring “how current and future identities are shaped by ideas about the past”. She works with history, folk traditions and archives to “connect the public, especially young people, to mythologies about personal, local and national identity”, particularly in rural English culture. An ongoing body of work of hers called Of Their Own Volition involved research and public participation that excavated the fluid context for blacking-up in traditional Border Morris Dancing. The work questions context, perception and tradition. However, she was compelled to remove earlier works from this series relating to Border Morris Dance.

I asked her what motivated or inspired her to research the Border Morris Dance tradition, she told me that she “felt an urgency to revisit portraits of morris dancers with blackened faces I’d made almost 10 years previously after becoming increasingly uncomfortable with the explanations I was asked to give in their defence. The final catalyst for this was when one of my images was used for a photography conference at the Tate but was then censored after it provoked complaints.” The subject is close Claridge’s heart, as the artist herself comes from a family of morris dancers. The explanation given for blacking-up in border morris “replicated a very old form of cheap and easy sooty disguise. I was told this was adopted by dancers for a range of reasons: to avoid recognition from potential employees, to beg anonymously, to bring luck – and fertility – as a pretend stranger and/or to look scary to ward off evil spirits. No reasons for disguise were related to race, I was told, and any conflation with derogatory black and white minstrel blacking was unfortunately mixing visuals with entirely different histories and motives.” This received knowledge led Claridge to seek evidence by speaking to experts, visiting key sites and digging into archival material.

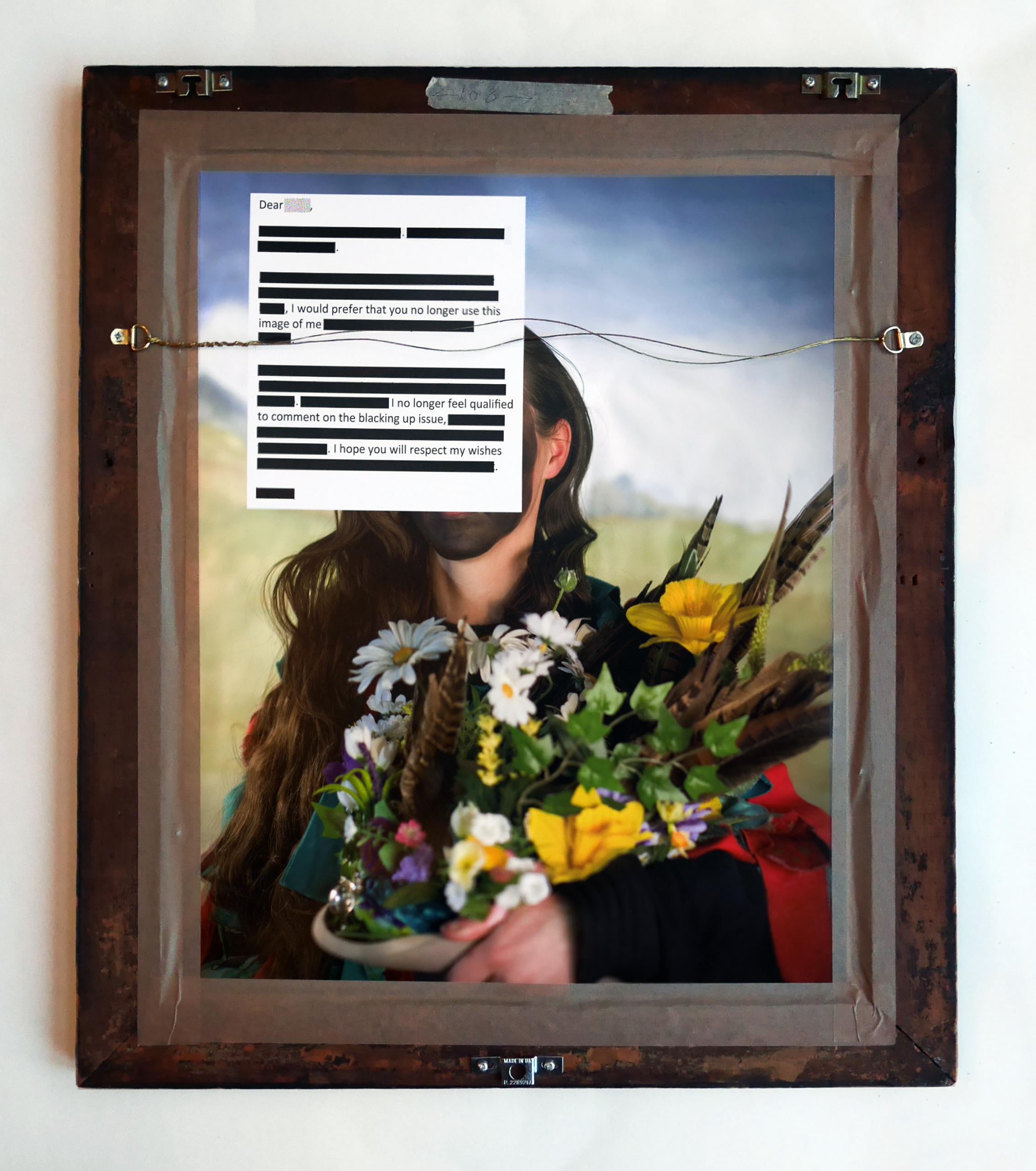

However, her research did not uncover clear motives for blacking-up. “I started to recognise that finding historical evidence is only a small part of the issue. The impact of blacking up in performance (of any kind) today has unavoidable aesthetic links to the deliberately damaging racial stereotypes of the black and white minstrels. Even if undisputable evidence pointed to a non-racial origin for morris blacking, its continued use for any reason after the acknowledged harm of minstrelsy has to be questioned.” Part of the work involves a series of portraits of contemporary Border Morris dancers. One of the photographs that Claridge showed me is of a woman with long flowing brunette hair blacked up, holding a bouquet of local flowers – daisies, daffodils, ivy and bird-feathers – staged against the backdrop of a painted scenery of washed out grey clouds and English mountains. Claridge is unable to show this portrait, and other similar photographs, in exhibitions as the sitter withdrew her permission when the artist invited her to contribute to the research on blacking-up. Claridge has since re-imagined the image by masking the subject with the letter that the sitter sent to the artist. The letter, with personal information redacted, says “I would prefer that you no longer use this image of me… I no longer feel qualified to comment on the blacking up issue… I hope you will respect my wishes”. The image is displayed on the back of a picture frame instead of the front as a metaphor for the original work’s journey into self-censorship.

This work has been selected for an open competition organised by the Nottingham based gallery The New Art Exchange but when Claridge proposed the series to other curators she was met with much unease and anxiety about the work. One curator responded that “It’s all very difficult terrain out there at the moment… have a good look around what black artists are doing in this area. The question of authorship is the critical issue it seems. Who can speak for who…We are finding people returning to very insecure places and taboo subjects raise anxieties.” Another curator told Claridge that “I imagine you know what sticky territory you are in (!), and I guess you know about other precedents for this conversation.”

Art institutions are becoming increasingly risk-averse and unable to deal with the questions that such works throw up, the people in the photographs feel exposed through the perceived racist lens and the artist is a white British woman…”who can speak for who”, it’s a taboo subject that may trigger the viewers’ anxieties but shouldn’t art be a tool to ask difficult questions, to provoke debate and transcend the divisions and borders relating to race and identity? The origins of blackfacing in border morris remains a mystery and has led the artist to question her own motivations: “The research journey has taken me to other, far deeper, questions about my power as an artist in gathering and sharing opinions. If I respect and repeat all views equally then my role is strangely inhuman, if I assert my own opinions, am I unfairly using my position? My nature has been exposed and tested: I’m keenly aware that I don’t like conflict and the risk of upsetting people deeply makes me anxious. It’s also apparent that I don’t like power being misused and I hate inequality. This is what motivated my drive to seek evidence (or lack of it) for morris blacking at the start, to see if my own work had a case to answer in this regard. I’ve concluded that it has; I won’t exhibit the original morris portraits again without significant alterations and my work evolving from this research more transparently references the problematics of power, blurred histories and appropriation…”

Increasingly, artists are forced to self-censor due to the possible backlash not only by curators, academics and the community, but also from fellow artists. It is part of a wider problem that I highlighted in a blog for the Manifesto Club on the self-censorship of a young adult novel by Amélie Wen Zhao. This is worrying for artistic freedom.

As Claridge says, there is “a sadness that it should come to this and a question of where exactly this is that we have come to. I remain unsure.”

Manick Govinda is a freelance arts consultant, artist mentor, campaigner and curator. His writings can be found here.

Faye Claridge’s work Blackout will be exhibited at NAE Open from 13 July to 8 September 2019.[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1562063442406-116696fa-3728-1″ taxonomies=”15469″][/vc_column][/vc_row]