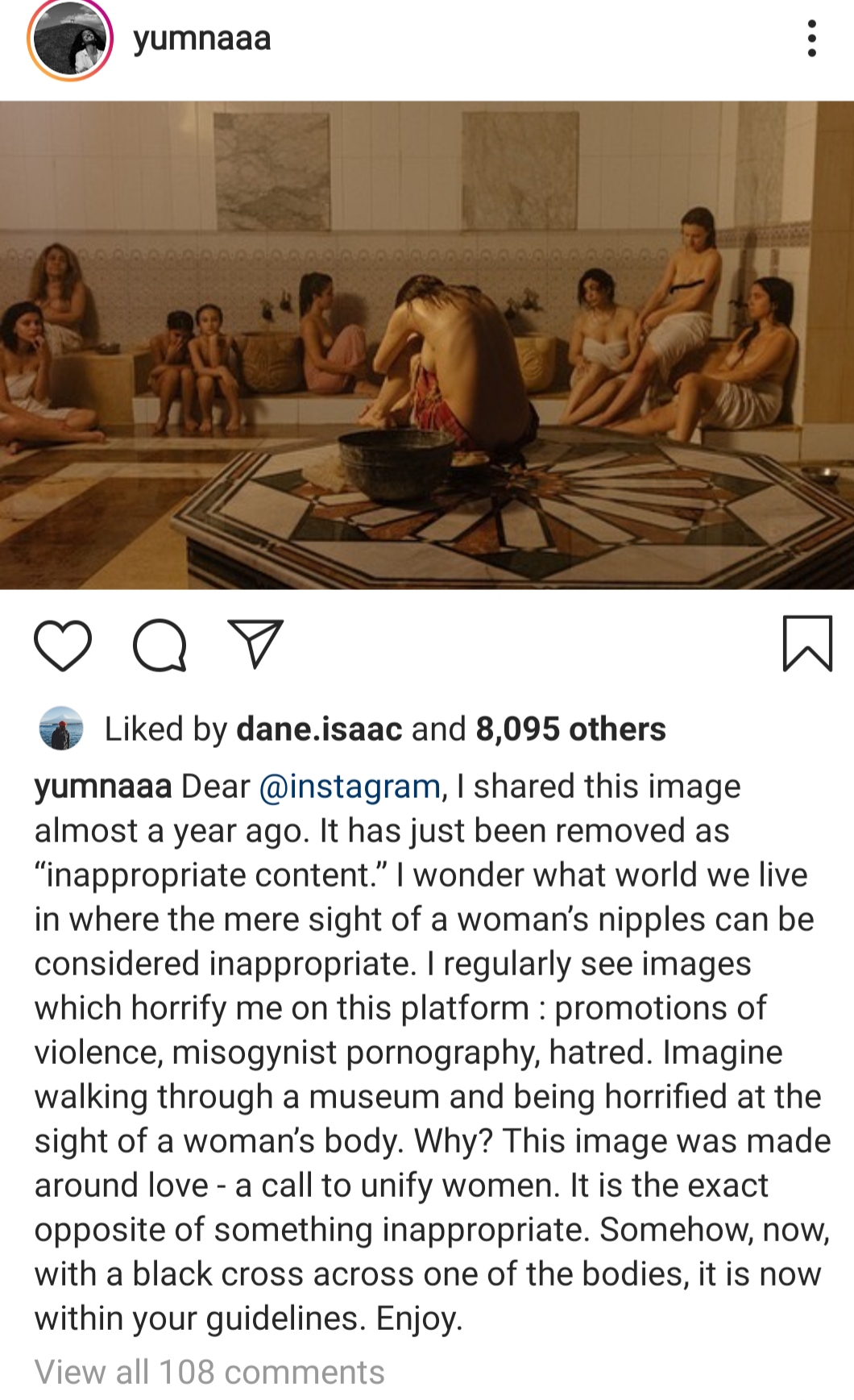

In September 2019, London-based photographer Yumna Al-Arashi announced that one of her photographs, showing women in a hammam, had been taken down by Instagram because, according to the platform, it fell foul of the community’s standards on adult nudity.

Name of Artwork: Shedding Skin

Artist: Yumna Al-Arashi

Date: September 2019

Brief description of the artwork

According to the artist, the work is a play on Orientalism, and specifically the way Arab women’s bodies are represented by white men. Made by a woman and taking a woman’s point of view, the work counters all the images of bodies that are supposed to represent women like the artist herself, but have nothing to do with her lived experience. The hammam, which Orientalism exoticises and eroticizes, is, in fact, a space where women can come together without judging each others’ bodies. It is the opposite of an eroticized environment. There is something healing and unifying that Al-Arashi sees in the all-women hammam, which she wants to convey to the audience through this staged image.

What triggered the takedown?

Shedding Skin fell foul Instagram’s Community Standards on Adult Nudity and Sexual Activity, which restrict photographic representations of nudity “because some people in [the Instagram] community may be sensitive to this type of content.”

The Instagram community comprises over one billion people globally, raising the question of whether it is at all possible to cater to the sensitivities of such a broad range of ‘community’ members.

Nudity, by the company’s definition, includes “uncovered female nipples” though there are exceptions for nipples represented in the “context of breastfeeding, birth-giving and after-birth moments, health-related situations (for example, post-mastectomy, breast cancer awareness or gender confirmation surgery) or an act of protest”. Male nipples are permitted while transgender nipples are banned or allowed depending on how the platform’s algorithms interpret the gender of the model. Painting and sculptural representations of nudes are exempt from restrictions, but photography is not. Algorithms occasionally mistake a painting or sculpture for a photograph and remove it, as happened with the Venus of Willendorf, or as it regularly happens with Betty Tomkins’ work, or with Courbet’s painting Origin of the World, which led to an eight year court case.

What action did Al-Arashi take?

Al-Arashi censored her own image, by concealing all visible nipples (see the figure second from right) and reposted it with a direct appeal to Instagram.

Al-Arashi’s second Instagram post

Next day, after it received over 6,000 likes, the image was removed and Al-Arashi, now considered a repeat offender, was blocked (according to Instagram parent Facebook, temporarily) from using Instagram’s branded content tools. It seems that the algorithms analyzing the image still saw too much nudity in it. Al-Arashi appealed the decision, but got no response: the situation many artists find themselves in.

Al-Arashi reposted the censored image in order to stay within Instagram’s terms of service “but I felt necessary to include the open letter [to Instagram] when I did. The censored image remains on view.

Al-Arashi contacted Index on Censorship who put her in touch with Svetlana Mintcheva, programme director at the US based National Coalition Against Censorship, currently running a campaign called #wethenipple.

Mintcheva brought the original image to the attention of the Facebook policy team as an example of valuable artistic expression that the company’s current guidelines do not allow on its platforms.

It was one among the works brought up in the discussion with Facebook and Instagram resulting from the #wethenipple campaign. As part of ongoing discussions, Facebook and Instagram held a meeting between artists and artistic freedom activists and Instagram tech and policy representatives. The goal was to discuss company content standards and enforcement with artists working with the human body and hear their concerns and to look for solutions. The meeting was held at Facebook’s HQ in NYC where, ironically, another work by Al-Arashi was on show for a period of time.

Yumna Al-Arashi’s work from Northern Yemen (centre) displayed at Facebook HQ in NYC

Facebook’s concerns about photographic nudity were:

- sensitivities of some viewers

- the difficulty of age verification

- confirming the subject of the photographs has given consent.

In addition, a question was raised around the perennial challenge of drawing a clear line between art and pornography as well as between art and photography that is not artistic. Indeed, a member of the Facebook policy team questioned how Al-Arashi’s work can be distinguished — as art — from a mere photograph of a hammam.

Possible solutions relating to Al-Arashi’s case

Creating artist verified accounts

This is problematic as it creates a hierarchy and raises questions about who is an artist and who can be verified as such. Nevertheless, it could allow a lot more content to be posted and go some way towards destigmatising the nude body.

Greater user control

If a user does not want to see a nude, there should be an option of filtering out content along the same lines as Facebook and Instagram offer regarding violent content. Once the filter is in place, you would need to click to remove the blocking filter to see the image.

Guidance on appeals

As content is regularly taken down by algorithms even though it conforms to guidelines, guidance will give individual artists instructions on how to appeal take-downs.

In line with Article 19’s campaign calling on “social media platforms to provide a human-rights centred process that guarantees notice, the right to appeal and transparent reporting when content is blocked and accounts removed”. This is very similar to the clarification of guidelines above.

Facebook’s response

The policy team said they were considering changes to policy, especially where clarification of guidelines and user controls are concerned.

Personal reflection by Yumna Al-Arashi

“Shedding Skin is an important piece of work for me, made in direct response to [President Donald] Trump’s Muslim ban. It had been up since 2018 and I felt that it had got over the takedown hurdle, and was appreciated for its artistic value. I feel that this is a strike against me, and that if I strike back I risk having my account deleted which would really damage my career.”

“When Instagram takes your privileges away and censors your work it is potentially so damaging. The message is that your account is pornographic or sexual in nature and you are barred from participating in our economy. I can still post – but it makes me not want to. It feels like I am on some kind of list, and if I appeal another takedown I might lose everything. Even though I don’t currently use Instagram’s branded content tools, it doesn’t mean to say that I won’t use them in the future.”

Personal reflection by Svetlana Mintcheva

“Facebook and Instagram are not going to make changes because they believe in artist rights or any other rights. The work, as originally conceived, still violates community standards, as does any other work containing photographic nudity, no matter how artistically valuable and important it may be. And unfortunately, Yumna’s hope that her work had remained up so long due to its artistic merit is unfounded; the nudity had simply not been noticed.”

“As private companies, social media platforms don’t have to conform to First Amendment protections in the United States and can decide to censor specific content. Free speech may be celebrated by Mark Zuckerberg in his public speeches, but free speech is only valuable to Facebook and Instagram as long as it works in harmony with their business model. And their business model is based on engagement: Facebook and Instagram want to satisfy the needs and desires of the largest number of people so to engage more users more actively and collect the largest amount of data.”

“Some critics say Facebook is prudish. It is not prudery that guides the company, it is their business model. Which is also true in general for any actor competing in a capitalist economy. The problem is Facebook and Instagram have a de-facto monopoly on the sharing of visual content widely — other artist friendly sites exist, but the audiences they reach are very small by comparison. As a result Instagram has the power to determine what art can circulate to global audiences. If a similarly broad platform for sharing images existed, public pressure would have more leverage in demanding art-friendly content guidelines. Perhaps it is time to think of an alternative platform, a non-profit platform that is based on a different business model and built in view of the public interest. This could be underpinned by a set of social media best practices endorsed by artists and museums. However, I wouldn’t be too optimistic; creating unity among artists on the issues is a challenge in itself. And questions about consent and age verification are hard to resolve and require resources — a public platform may be similarly reluctant to arbitrate between pornography and art.” [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]