[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The award-winning writer speaks to Rachael Jolley about the inspiration for her new short story, written exclusively for Index, which looks at the idea of ageing, and disappearing memories, and how it plays out during lockdown.”][vc_column_text]

British-Canadian writer Lisa Appignanesi has found lockdown a difficult time to write, but despite this she has created a new short story exclusively for Index.

British-Canadian writer Lisa Appignanesi has found lockdown a difficult time to write, but despite this she has created a new short story exclusively for Index.

Appignanesi, a screenwriter, academic and novelist, said: “It’s very hard to move within the instability of the time to something imaginative.”

Her story, Lockdown, focuses on an older man, Arthur, who reflects on his past in Vienna during the period between the two world wars.

Appignanesi has a long relationship with the Austrian city.

“I’ve done an awful lot of work on Viennese literature and, indeed, on Freud, so Vienna always feels very, very close to me and I lived there for a year,” she said.

“Vienna is a fascinating place. It was a great city – first of all head of an empire with many, many immigrant groupings in it, and then when it lost its imperial status in World War I it was a very impoverished city.”

She says the period of lockdown focused her mind on the restrictions imposed upon the elderly. “I have long thought about what happens to the mind within the body, people’s relationship to time in that sense. You grow old and stuff happens to your body and, initially at least, it doesn’t seem to affect your mental capacity and the way you grow through time as you are living it.”

She is also interested in the idea of people being present in different ways and how, for instance, the potential anonymity and the disembodied nature of Twitter means that people can unleash their anger differently from how they would if they were in the room with someone.

“Some of the rampant emotions of our time, particularly anger,” she said, “were to do with the fact that people on Twitter are not only anonymous but they are disembodied.”

In an article for this magazine in 2010, Appignanesi wrote: “The speed of communication the internet permits, its blindness to geography, seems to have stoked the fires of prohibition. The freer and easier it is for ideas to spread, the more punitive the powers that wish to silence or censor become.”

Appignanesi, a long-time campaigner for freedom of expression, was born in post-war Poland as Elżbieta Borensztejn. Her Jewish parents had what she has described with understatement as “a difficult war”, hiding under different aliases to escape arrest. The family moved then to Paris, which she remembers, and later to Montreal, Canada. She once told BBC Radio 3 that she “grew up with the ghosts of those that died in the concentration camps”. Given the family history, it is no wonder she worries about authoritarian governments and restrictions on speech.

She is now concerned about how governments are changing the rules of freedom of expression while the world is distracted by Covid-19, and the threats that may manifest themselves. “Your attention is distracted by something – something happens behind the scenes, and usually the same people are doing the distraction. This time it was the virus.”

One news item that grabbed her attention recently was about the closure of Guatemala’s police archives (see page 27), a library of information about the country’s civil war. Her concern is that “those archives are about the disappearances of people under the dictatorships, which were lethal”.

As others track governments who want to control the national story, Appignanesi says we must learn from history.

“It’s very important for our documents in Britain to be interpreted in different ways, and supplemented by stories we don’t know.

“There are always new histories to discover.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” color=”custom” custom_color=”#dd0d0d”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The freer and easier it is for ideas to spread, the more punitive the powers that wish to silence or censor become.”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Lockdown by Lisa Appignanesi:

Arthur was old. Very old. So old that when the word “lockdown” had made its way onto the radio news he was listening to with only half an ear – and even that half tuned to inner voices – he had thought they were talking about him.

It seemed the world was joining him now. In lockdown.

But the whole country had been in metaphorical lockdown for some time, he reflected, its politicians preventing every connection between a fragmented people except angry sparks or empty boasts.

Lockdown was a perfect word to describe his present condition: confined to his cell for his own good by a greater authority. If he promised not to riot, he was allowed out for exercise at regular intervals.

Yet the notion of exercise took all the pleasure out of movement. He preferred to think of it as a walk, better still, a passeggiata. He always dressed carefully for the occasion – a suit, perhaps a silk waistcoat, a bow tie. The joy of a stroll was in part that people looked at, and greeted, each other – even smiled. So no stretchy joggers and sweatshirts for him of the kind his grandchildren wore. He liked form. He had always been something of a dandy, though these days, as he heaved what seemed to be boulders rather than legs along the streets, it was harder to turn a casual half smile on the world and appreciate its offerings. But then his senses, too, were in all but lockdown. His new glasses had him stumbling, the ground far closer than where he had last left it, as if he had shrunk back to childhood and well below what was once an adequate height for a man of his generation.

His first grandson had once asked him if he was named after King Arthur since he had a round table and Arthur hadn’t liked to contradict him – but the only table that had featured in his own childhood had been the one at the Professor’s house in Vienna. He played happily under that while the adults talked and occasionally the Professor would put a hand below the edge of the tablecloth and tousle his hair, then pat him as he did his dogs. He liked the Professor, who gave his name a proper ‘T’ – Artur. In fact, it was the writer who was called the professor’s “doppelgänger” who was responsible for Arthur’s name.

Doppelgänger was a word he learned early. Another, heard from beneath the table, was Zensur. He had thought that had the word hour in it, had thought maybe it meant ten o’clock, zehn Uhr. Amidst the chatter of the adult voices, he saw TEN blotting out all the hours that came before, a censoring hour.

Maybe that’s why he had this odd relationship to time now, as he reached his midnight. He was convinced that at this late age he finally understood, was indeed living, what Einstein had meant about time slowing in the presence of heavy objects. Arthur was so light now, his bones s0 hollowed out, that time didn’t slow for him. It sped.

Or maybe its racing effect was linked to the fact that there was so little of time left that what had once been full and slow was now racing towards an end. The thought of death could no longer be censored or repressed. No bonfire could destroy it. But then it hadn’t really worked for the books either. They had sprung up in other editions and elsewhere.

Arthur had been born in Berlin just weeks after the great conflagration of books the Nazis had staged and only a few months after the Reichstag fire. His mother had been walking near the Staatsoper on the night of the book burning. She had loved Arthur Schnitzler’s work and had known him a little, so he had become little Arthur.

It was as well the Professor was still alive or he might have become Siggy, since his books were in that bonfire too.

Was that why he had spent his life in books and collected so many in the process? He looked up at the study’s walls lined in first editions, one side leather bound, the other brighter in their contemporaneity.

“Arthur?”

He checked that the voice was real and forced himself into the present.

In the doorway stood the young woman he liked to think of as his companion, though his granddaughter, Mia, had called her – in insisting on the need for her – an au pair plus. Stella was certainly more than his equal, not only as tall as he once had been but with poise and a razor-sharp intelligence he sometimes thought could penetrate his thoughts without him needing to speak.

So she knew he liked the fact she was decorous and she hadn’t – at least not yet – upbraided him for it, as his granddaughter would. Stella was completing a PhD at Cambridge, and with a rueful smile admitted that she had been completing it for an unconscionable while, which most recently had included divorcing her husband. That was why she found herself in need of a room and an extra wage. No one had imagined lockdown.

Now she wanted him up and ready to begin the Sisyphean task of the morning passeggiata.

His study door opened onto a terrace and from there down into communal gardens, a square where the trees today were in full glorious flower. He was a lucky man. Doubly lucky that his granddaughter had somehow gifted him this magnificent creature.

“We’re going to begin today,” Stella said when they paused for him to catch breath beneath the flowering cherry. The sky between its branches was a Mediterranean blue. The blackbirds were in full throat. The young Americans with their twin toddlers weren’t out yet.

“I’m not ready.” Arthur heard the plaintive high pitch in his own voice and rushed to blur it in a cough.

If you wish to read the rest of the extract, click here.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Lisa Appignanesi is an award-winning writer and campaigner for free expression. She is the author of many books including Memory and Desire, Losing the Dead and The Memory Man.

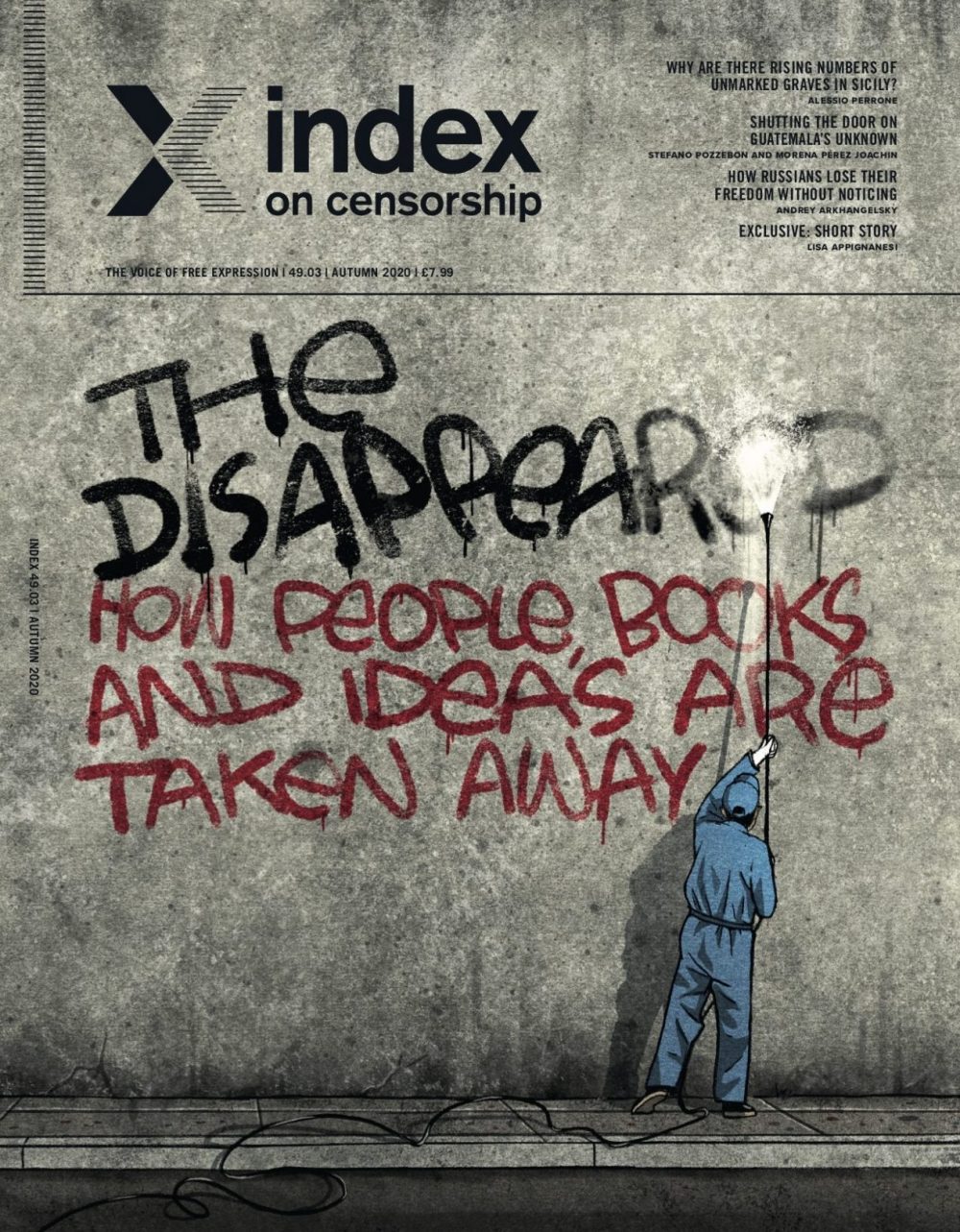

Rachael Jolley is the former editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship’s autumn 2020 issue, entitled The disappeared: how people, books and ideas are taken away.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2020 magazine podcast featuring Hong Kong-based journalist Oliver Farry, who discusses the crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrations in the region

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]