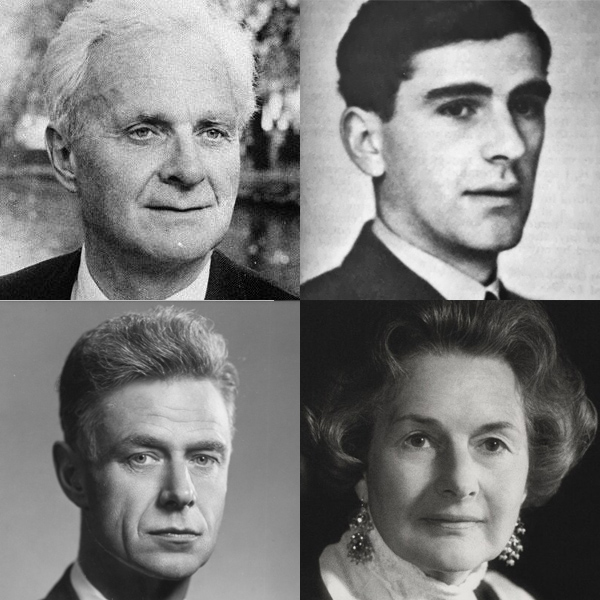

Elizabeth Longford’s involvement as one of the founders of Index on Censorship should come as no surprise. By the time she signed the deeds of the charity she was established as a prominent newspaper columnist and biographer and had become a regular on the radio programme Any Questions as what would now be called a celebrity pundit. Driven by a socialism forged in the Depression and her deep Catholic faith, she had an unswerving instinct for defending the underdog, despite her privileged background and her later fame as a royal biographer.

She was born Elizabeth Harman into a family of doctors and spent a comfortable childhood in Harley Street, London. At Oxford she was part of a gilded generation of intellectuals that included philosopher Isaiah Berlin, Hugh Gaitskell, who later became leader of the Labour Party, and poet Stephen Spender, her co-founder at Index. It was at Oxford too that she met her husband Frank Pakenham, later Lord Longford, describing him as “like a Greek God”.

After university, she went to work for the Workers’ Educational Trust in Stoke, where her socialism took root. She later said: “Stoke became as much a part of me in 1931 as Oxford had been for the past four years. The working-class ethos had become my own”.

When her husband took a post as a politics lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford, Elizabeth joined the local Labour Party and stood, unsuccessfully, as a candidate in Cheltenham in 1935. She admitted to an “addiction to motherhood”, but after bearing the last of her eight children, she again stood as a Labour candidate in 1950, this time in Oxford, but never did become an MP.

She had become a Catholic in 1946, following the earlier conversion of her husband. Her daughter, the historian Antonia Fraser, told Index Elizabeth was particularly affected by the treatment of the Catholic Cardinal Jozsef Mindszenty by the Communist authorities in Hungary. Mindszenty was a vocal opponent of Communism, who was the subject of a show trial in 1949. He was released from prison during the Hungarian uprising of 1956, but after the Soviet invasion crushed the revolution he was forced to flee to the American embassy in Budapest, where he lived until 1971. He was finally allowed to leave Hungary for exile in Vienna around the time that Index was founded.

Elizabeth’s career as writer began in the 1950s, when she was invited by Lord Beaverbrook to write a column on the Sunday Express. She later also wrote for the News of the World and the Sunday Times, usually on domestic subjects such as parenthood.

She was in her fifties when she turned to historical biography. Her first bestseller was Victoria RI, published in 1964 and she went on to write an acclaimed two-volume life of Wellington and works on Churchill, eminent Victorian women, Byron and the house of Windsor. She was the biographer of both the Queen and the Queen Mother.

She wrote her autobiography, The Pebbled Shore, to mark her 80th birthday in 1986 but did not stop there. Royal Throne, published in 1993, designed as a reflection on the future of the royal family coincided with the Queen’s “annus horribilis” when Charles and Diana separated. She remained, in later life, a staunch supporter of the monarchy.

Elizabeth Longford sat at the head of a dynasty of writers: her son Thomas Pakenham, daughters Antonia Fraser, Rachel Billington and Judith Kazantzis and granddaughters Eliza Packenham, Flora Fraser, Rebeca Fraser and Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni.

The one great tragedy of Elizabeth’s life was the loss of her daughter, Catherine Pakenham, in a car crash in 1969. The Catherine Pakenham prize for young women journalists was established in her memory.

Her own legacy is marked by the Elizabeth Longford Prize for Historical Biography.

But her legacy is also Index on Censorship, which continues to fight for the principles of freedom of expression and liberty of thought which she held so dear.

Flora Fraser, chair of the Elizabeth Longford Prize for Historical Biography, writes: “My grandmother believed passionately in the mission of Index on Censorship to highlight the work of fellow writers and scholars, wherever in the world they faced obstacles to freedom of expression.”