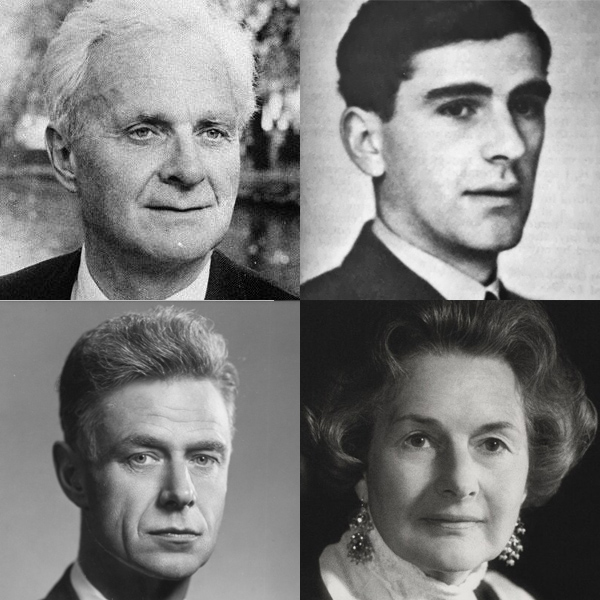

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116457″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Of the “gang of four” who signed the documents establishing the Writers and Scholars Education Trust fifty years ago on 25 March 1971, Peter Calvocoressi perhaps embodied the spirit of that trust more than the other three. He was both writer and scholar. And many things besides.

In 1968, Calvocoressi published what became the definitive work on post-war global history, World Politics Since 1945. The book, which the Sunday Times called “masterly”, has remained in print ever since and stretches to almost 900 pages.

It is one of more than 20 books he wrote during his lifetime, which stretched from a Who’s Who in The Bible to Suez: Ten Years After.

His academic credentials were equally impressive: he was Reader in International Relations at the University of Sussex, a post created especially for him.

The Calvocoressi name hints at his most international of upbringings. He was born in Karachi, in what is now Pakistan, but then was British India, making him a British subject. However, in one of his autobiographical works he considered himself “entirely Greek”, being part of the Ralli family who left the Aegean island of Chios in the 19th century diaspora.

Peter’s parents moved to London in 1910 and he was born two years later. Peter was educated at Eton and Balliol College, Oxford where he got a first in modern history.

He was called to the Bar in 1935 and shortly thereafter was recruited into the Ministry of Economic Warfare, based at the London School of Economics.

Soon after the start of the Second World War, Calvocoressi resolved to volunteer to become more active in the war effort. After a day of tests at the War Office he was told he was “no good, not even for intelligence”.

That conclusion proved to be very wrong. Soon after, through a contact, he was interviewed by the Air Ministry and shortly after became an RAF intelligence officer. In 1942, his gift for languages saw him plucked out for duty to Bletchley Park, the wartime home of the Allied codebreakers.

There he worked in the famous Hut 3, which decrypted messages from Germany’s Enigma machines and passed intelligence, known as Ultra, to the Allies’ military commanders. His time at Bletchley, where he went on to lead Hut 3, is described in his revelatory book Top Secret Ultra, published in 1980, shortly after the activities of the Allied codebreakers were first made public.

After the war, Calvocoressi was asked to participate in the Nuremberg Trials, helping obtain evidence for the Allied prosecution team and in which he cross-examined former German Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt.

Calvocoressi spent much of the Fifties researching and writing his Survey of International Affairs series, revealing his firm grasp of global politics and international relations.

He was asked to join the council of the International Institute for Strategic Studies in 1961 and later was instrumental in the early years of Amnesty International.

In 1967, he was called on as an independent expert to find out whether Amnesty had been infiltrated by British intelligence agents – his investigation proved that it had not. He steadied the ship at the organisation and served on its board from 1969 to 1971.

Throughout the decade, Calvocoressi was a member of the UN’s Commission on discrimination and the protection of minorities and became a member and chairman of the Africa Bureau, which lobbied against apartheid, at the request of his friend David Astor, owner and editor of The Observer.

Calvocoressi’s international experience and erudition made him an obvious choice to be asked to help found the Writers and Scholars Educational Trust, the organisation that is today better known by its working name of Index on Censorship.

Calvocoressi contributed to Index’s work in the early years but the world of publishing came calling.

He became a partner in publishers Chatto & Windus and Hogarth Press and was later asked to be chief executive of Penguin Books, a position he held until 1976. He continued his prodigious writing output throughout the Eighties and Nineties.

He had strong freedom of expression values too. He believed in the freedom to publish – writing a book of the same name which Index published in 1980.

He also believed in the freedom of the press but not at any cost.

In the case of the Pentagon Papers, the revelations around US involvement in the Vietnam War, he wrote to the Sunday Times about the decision of US newspaper editors to publish them.

He wrote: “The newspapers maintained that they were entitled to print the Pentagon Papers because the documents had come into their possession and they themselves judged that publication could not harm national security.

“But is an editor in a position to judge this? Surely not, for he cannot know enough of the background to tell whether he is giving something away.”

“Governments must have secrets whether we like it or not, and the power to preserve them. I am not denying that our own government overdoes the secrecy, sometimes absurdly so.”

What readers of that letter did not know, of course, was Calvocoressi’s personal involvement in the biggest secret of the war: the codebreaking at Bletchley Park.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]