In June 2015, a national newspaper in Britain started a campaign to have a play banned. This surprised me for two reasons. One: clearly no one had told the Daily Mirror about the Theatre Act 1968, which abolished the state’s censorship of the stage and did away with the quaintly repressive (if that’s not an oxymoron) notion of the Lord Chamberlain’s red pen. Two: the play in question was mine.

I wrote An Audience With Jimmy Savile to show how the late entertainer managed to get away with a lifetime of sexual offending. But despite the play’s very public service intentions, the Mirror started a petition to stop it. And so, for a moment, I found myself in some exalted, unwarranted company: Ibsen and George Bernard Shaw had plays banned (Ghosts and Mrs Warren’s Profession, respectively). Inevitably, however, the Mirror’s cack-handed attempt at censorship failed and the play went ahead.

The episode was instructive, however. Because while it’s true that “we” – that is, the British state – don’t ban plays any more, a powerful and unhealthy censorious reflex still exists and there are clear signs that the urge to stifle and to repress has been growing stronger over the last few years. That repression takes many forms: a social media backlash here, a not-very-subtle government threat there – but it’s real, it’s unhealthy and it’s profoundly worrying.

Censorship in the West is real

We are not, of course, in the same league as China – where a play bemoaning their treatment of Uyghur Muslims, for example, would never be officially sanctioned – but as playwright David Hare told me in an email exchange for this article, censorship in the West is real. It just isn’t called that anymore.

“Is there censorship in the sense that there is censorship in Iran, Russia or China? Of course not. Nobody’s physical survival is threatened,” he said.

But he does seem to say that the BBC has, in effect, become a censorious government’s useful idiot. (My phrase, not his.)

“The BBC has a current policy of deliberately not alienating the government,” he said. “They have chosen the path of ingratiation rather than asserting their independence. The result is, effectively, a range of subjects [which is] hopelessly narrowed. Hence the ubiquity of cop shows. Even medical dramas are forbidden if they stray into questions of ministerial health policy.”

Some might accuse Hare of pique, given that a TV adaptation of his most recent play, Beat the Devil, starring Ralph Fiennes, was turned down by the BBC. He says it was rejected because of the subject matter: Covid-19. (Hare became gravely ill with the virus and the play depicts him on his sickbed, despairing of the government’s response to the pandemic as they “stutter and stumble” on the airwaves.)

Indeed, when Hare went public with his attack on the corporation for turning him down, it refused to comment and the inference was that this was an editorial judgment and not a political one. But, says Hare, they would say that wouldn’t they?

“Censorship in the West,” he said, occurs “in the impossible grey area between editorial judgment and active prohibition.”

He’s right. The most egregious recent example of censorship-in-all-but-name occurred in 2015 when the National Youth Theatre (NYT) cancelled a production of the play Homegrown, about the radicalisation of young Muslims, two weeks before it was due to open. The executive who made the decision cited “editorial judgment” as a factor.

But, thanks to Freedom of Information requests from Index on Censorship, a fuller explanation emerged soon afterwards. An email from the NYT executive responsible for cancelling the production contained the following line: “At the end of the day we are simply ‘pulling a show’ … at a point that still saves us a lot of emotional, financial and critical fallout.”

In other words: “Yes, we might be censoring an important piece of work featuring the two most underrepresented groups on stage – Muslims and young people – because we are worried about defending ourselves from a backlash which hasn’t happened yet, but we don’t really fancy defending free speech and trying to ride out the storm because it’s too much hassle. So, let’s just cancel it and put it down to editorial judgment. Oh yeah – and safeguarding. Even though putting on work like this should be our raison d’etre.”

The director of the piece, Nadia Latif, was understandably shellshocked. A few weeks after the cancellation she said the creative team were “genuinely still reeling. The gesture of someone silencing you is a really profound one. You give your heart and soul to something, and someone comes and shuts it down. It’s like they’re saying my thoughts and feelings are no longer valid.”

And to refer the audience to my earlier point, it’s happening more and more. Albeit behind the scenes, and sometimes in ways you don’t get to hear about. There are two reasons for this: the pandemic and the nature of the current government.

Covid and censorship

The pandemic first. Although Hare’s Covid-19 polemic made it to the stage, that was the exception not the rule. I can’t find any other examples of plays critical of the current government being either staged or commissioned.

That would seem to be directly related to the fact that, during lockdown, every theatre in the country was desperate for financial assistance from the Treasury. So regrettably, but perhaps not surprisingly, few gave the go-ahead to works which bit, or even nibbled, the only hand that could feed them.

This isn’t speculation. When the producers of my play The Last Temptation of Boris Johnson – an unashamed takedown of the prime minister – tried to book it into theatres for a national tour post-pandemic, more than one theatre said, in effect: “We are worried we will lose our Covid grants if we put on a play like that.”

Which brings us on to the current Conservative government and its attempt to take a long march through our cultural, creative and editorial institutions.

When the Tories couldn’t get the former Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre installed as the new boss of the broadcasting regulator Ofcom, they simply scrapped the selection process and ordered that it start again, putting Dacre’s name forward once more – even though, first time round, the selection panel described him as “not appointable”. Dacre has now voluntarily withdrawn and gone back to the Mail.

Someone who was appointable and acceptable, however – to the government, that is – was Nadine Dorries, the new secretary of state for digital, culture, media and sport. Putting Dorries in charge at DCMS was a bit like getting Herod to run the local nursery. Within days of taking over she reportedly started issuing threats against our premier creative organisation – the BBC – which, in her view, was guilty of not sufficiently toeing the line.

After the BBC radio presenter Nick Robinson hectored Johnson in an interview – “Stop talking, prime minister” – it’s said that Dorries told her advisers that Robinson had “cost the BBC a lot of money”.

A bit like the take on Aids policy from the satricial show Brass Eye – is it Good Aids or Bad Aids? – there is Good Censorship and Bad Censorship. The decision to ban Homegrown falls into the latter category.

The social media backlash

But the act of self-editing – in effect, self-censorship – has more going for it. As Hare puts it: “There is all sorts of subject matter I wouldn’t tackle – but entirely because I’m not good enough. I have always refused anything which represents life in Nazi concentration camps, since I don’t trust myself to do it well enough to do justice to what happened. If I don’t think I can do justice to the real suffering of real people, then I avoid, [although] I take my hat off to great writers who are able to expand subject matter at a level where it vindicates the idea of writing about absolutely everything. More power to them.”

But it’s complicated, of course. The worry is that more and more writers, terrified of a vicious social media backlash, are self-editing to an extent that is unhealthy. There are few, for example, who would now dare to pen a play that took a critical, coolly objective look at both sides of the argument over transgender rights – even though tackling difficult subjects and representing “problematic” points of view is, arguably, one of theatre’s prime functions. What could be more relevant, and on point, than a play like that?

One playwright who did sail into these waters was Jo Clifford. Her play, The Gospel According to Jesus, Queen of Heaven, casts Jesus as a trans woman. During its 2018 run at Edinburgh’s Traverse Theatre, an online petition demanding the play be banned garnered a healthy – or rather unhealthy – 24,674 signatures. Soon after that she spoke of how artists and writers were “on the front line of a culture war that will only deepen and strengthen as the ecological and financial crisis worsens and the right feel more fearfully that they are losing their grip on power”.

So, at a time when writers and playwrights need to be bolder, the signs are that they’re becoming more and more cowed; hence Sebastian Faulks’s bizarre announcement that he will no longer physically describe female characters in his novels. Fortunately, most of his peers seem to disagree with him. A recent open letter signed by more than 150 eminent writers, artists and thinkers including JK Rowling, Margaret Atwood and Gloria Steinem warned of “a fear spreading through arts and media”.

“We are already paying the price in greater risk aversion among writers, artists and journalists who fear for their livelihoods if they depart from the consensus, or even lack sufficient zeal in agreement,” it said.

Then again, not everyone agreed with the letter. Author Kaitlyn Greenidge said she was asked to sign it but refused, saying: “I do not subscribe to [its] concerns and do not believe this threat is real. Or at least I do not believe that being asked to consider the history of anti-blackness and white terrorism when writing a piece, after centuries of suppression of any other view in academia, is the equivalent of loss of institutional authority.”

Like I said, it’s complicated.

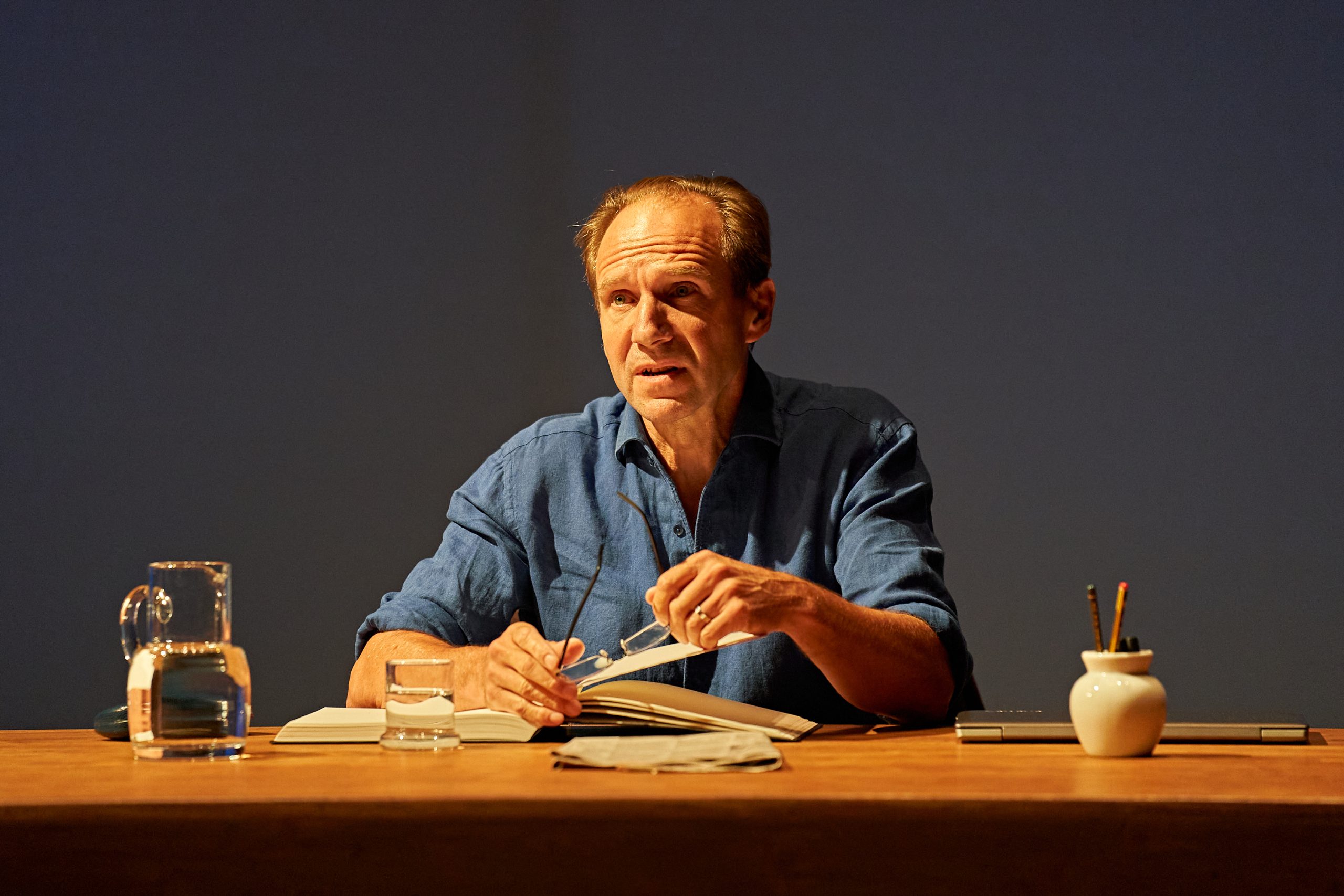

Promotional material for An Audience With Jimmy Savile. Photo: Boom Ents

The big question for writers, then, is this – if, like me, you believe that anything goes on stage, provided it’s not proscribed by law, how far should you go? Where do the (self-imposed) limits of free expression lie?

Those limits are different for each writer, of course. I would draw the line at, for example, depicting sexual assault on stage. My Jimmy Savile play showed the effects of it, clearly, on the main character – a young woman who’d been abused by him at Stoke Mandeville Hospital – but left the rest to the audience’s imagination. Sometimes it’s more powerful that way.

I would, however, defend the right of other playwrights to go further and include vivid scenes of sexual assault, provided it was for the “right” reasons. There would need to be a coherent dramatic justification for it and the creative team would be advised to have plenty of flak jackets ready. Anyone who tests the boundaries in this way will inevitably face accusations of prurience, unjustified provocation or worse.

The actor’s “thumb”

In 1980, when Howard Brenton showed a scene of homosexual rape in The Romans in Britain, the production found itself being prosecuted for gross indecency by Mary Whitehouse as part of her attempt to “clean up” Britain. (The prosecution failed when a key witness admitted that, from the back of stalls, what he thought was a penis might have been an actor’s thumb.)

A similar court case today would be unlikely. But then again there is always the Court of Public Opinion, powered by the rotten fuel of social media, which is arguably more scary and intimidating than the real thing.

I wouldn’t draw the line at giving free expression on stage to anti-Semitism, either. Sometimes the best way to destroy an argument is to bring it into the light. With one crucial proviso, which I will come to in a moment.

As a Jew who lost relatives in the Holocaust I am fascinated by the subject. I would love to see a play which explained where anti-Semitism came from. Or whether the definitions of it are justified. Are there internal contradictions there? (We fought the war to preserve our freedoms, but isn’t using the label “anti-Semitic” a destruction of one of our most cherished freedoms? As in, the freedom of speech?)

Any play which seeks to answer these questions would need characters espousing anti-Semitism – the more articulately the better, in my view – if they are to work properly.

My proviso would be that the anti-Semitism would need to be both contextualised and rigorously challenged. This could be done within the play – two characters arguing – or in the form of a post-show debate.

I would, for example, even have defended the right of writer Jim Allen and director Ken Loach to stage Perdition, their controversial 1987 play for the Royal Court, despite its disgusting anti-Semitic tropes.

The play accused Jews of “collaborating” with the Nazis during the Holocaust (is there a more loaded, insulting, inappropriate word in this context than “collaborated”?) and was based on the story of Rudolf Kastner, who negotiated with Adolf Eichmann to let more than 1,600 Jews flee Hungary for the safety of Switzerland.

Kastner, it is argued, should have done more to warn more Jews (not just the 1,600 that he rescued) of what was happening. Hence Allen’s line: “To save your hides, you [a Jew] practically led them to the gas chambers.” Disgusting, misjudged and morally wrong.

In the resulting furore, the Royal Court cancelled the play. But the decision to ban it, paradoxically, only increased support for it, and the poison it contained. I would have let it go ahead but tried to persuade Allen to make editorial changes. And if that didn’t work (and I doubt it would have done, although some controversial lines were excised during rehearsals) then I would have staged a debate, forming part of the show, which allowed the Jewish community to explain why the play was so offensive and misjudged. Education beats defenestration, every time.

The stage would be the perfect place to explore the arguments on both sides, but in particular to highlight the muddy thinking of the anti-Israel lobby, as personified by Sally Rooney, who recently decided to punish the Jews by forbidding a Hebrew translation of her latest novel. (Although making them read it might have been a more effective punishment.)

British theatre is not in a good place today. Where are the revolutionaries? The new, angry young men and women, the new John Osbornes? We don’t need to Look Back In Anger: it’s all in front of us, now.

Would a film like 2009’s Four Lions, a deeply moral but, to some, hugely offensive Jihadi satire, get made today? I very much doubt it.

We – all of us: writers, commissioners and directors – need to be braver.