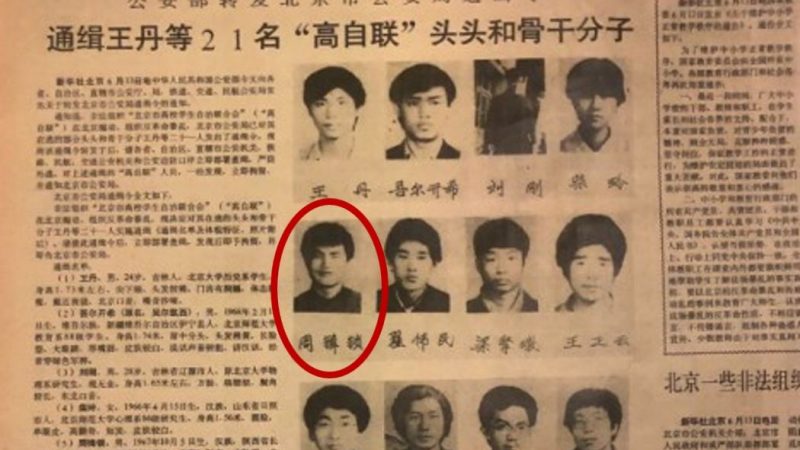

There was a time when Zhou Fengsuo wanted to change his name. It had become synonymous with the Tiananmen Square protests, which he had an instrumental role in leading. He’d helped with general organisation, he’d delivered speeches in the square, he’d provided medical help for those during the hunger strike –just a few of the hats he wore. For this Zhou was named as number five on the Chinese government’s most wanted list and was arrested shortly after the crackdown. He spent a year in Qincheng Prison, a maximum-security prison in Beijing, after which he was exiled to Yangyuan in Hebei province, a poor, rural area to be “re-educated”. Constant monitoring and police harassment became a part of his life and he struggled to earn a living. He couldn’t even get a passport to leave the country.

“I wanted to change my name to have a normal life,” he told Index ahead of the 33rd anniversary of the protests and the massacre that brought them to a terrifying and devastating end.

“But that was then,” he added.

Today the importance of keeping his name is paramount. The Chinese government would gladly erase it, alongside all memory of the massacre.

“We do whatever we can to preserve the memory and preserve the truth,” Zhou said, who has remained a staunch advocate for human rights in the years since, including being president of Humanitarian China and the Chinese Democracy Education Foundation. When we speak he is working on a Tiananmen museum in the town where he now lives in the New York metro area (he was finally given a passport and left for the USA in 1996).

Zhou is understandably proud of his role in the protest movements, which called for greater freedoms, especially in relation to freedom of speech and the media. They had been happening in pockets of China for several years by then and built to a crescendo in the spring of ‘89, described as like a “volcanic eruption” by Zhou. The main ones that took place in Tiananmen Square from April through to June were “China’s version of a festival of freedom” he said.

“It was exhilarating because for the first time people could have a taste of freedom. These were very joyful, hopeful moments, even though there was a sense of defiance,” he added. He has a particularly fond memory of 18 April 1989.

“I made a speech at the monument of the People’s Heroes where I compared the US Bill of Rights to the Chinese constitution. For me it was the first time I could speak out on these issues. These were my own views that I felt really strongly about and I had had to keep them to myself and all of a sudden, I was there in an important place with thousands listening. There was such a powerful feeling of freedom in the air. I was overwhelmed by the passion that people showed.”

Zhou said that even the most marginalised people felt there was hope. They even joked that thieves stopped stealing.

Zhou remembers the run-up to 4 June 1989 as one of the most peaceful times. He spoke of how people made homemade meals to send to the protesters and that “Coca Cola had just arrived in China and was considered a luxury – people would buy it for the students as a way to show support. It was incredible the feeling of solidarity.”

But then came the tanks.

“It was like an invasion of Beijing by armed troops,” said Zhou, who reckons there were around a quarter of a million soldiers by the time they turned on the students on the evening of 3 June.

“It was brutally senseless.”

Many of Zhou’s friends died on that fateful night and in the following days, with plenty of others arrested and put in jail.

“The government are guilty of murdering their own people,” he said.

No-one knows for certain exactly how many people were killed. Shortly after, the Chinese government said just 200 civilians had died. Other estimates place it in the region of thousands. In 2017, documents from the British ambassador to China at the time, Sir Alan Donald, said that as many as 10,000 had actually died.

The Chinese government has gone out of its way to erase the exact figure and surrounding memories. Any references to Tiananmen are carefully removed from books and the internet. The country’s censors work overtime to stay ahead of the game, blocking anything from obvious references like #tank to more obscure ones (#35 for 31 May plus four days; #6+si for the sixth month and si meaning four in Mandarin). Sometimes they even block the words “today” and “tomorrow”. Commemorative events – well-nigh impossible to hold in mainland China – are now off the agenda in Hong Kong too, which for years hosted a large memorial event in Victoria Park. Also in Hong Kong, the Pillar of Shame statue to honour those killed in the square was recently removed. There is a rumour it might reappear in Taiwan.

Despite the dangers, when it was the 25th anniversary of the massacre, Zhou returned to China, albeit briefly. He snuck back in due to a change in China’s immigration policy that allowed people in transit to enter for 72 hours without a visa. During that trip he was interrogated by the police who had also been in Beijing in 1989 but he was allowed to leave for the USA again.

Thirty-three years on and China remains as jumpy about the event as if it was yesterday.

As China’s long arm stretches further overseas, the attempts to eradicate its memory have arrived on distant shores. Just two weeks ago Zhou was in Prague on a panel with the Chinese dissident artist Badiucao. When there the event’s curator received a call from the Chinese embassy. The person who called her said that if she continued with the event it would hurt the feelings of the Chinese people and would damage Czech-Chinese relations. She ignored the call, but it left her and Zhou spooked.

“It was strange because Michelle didn’t publish that number and was not sure how they got hold of it,” he explained.

The Chinese government has found willing participants in this erasure game in the form of companies with close ties to China. Two years ago, for example, Zoom closed Zhou’s paid account a week after he held an event discussing the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. He also had a run-in with LinkedIn, who temporarily blocked his page and posts from being seen within China.

Zhou says that “US companies who do business with China will try to stay away from people like me.”

“Global trade and digital communications have enabled China to exert control even in the US. This wasn’t possible before, even in Nazi times. But China is much more dangerous now than Nazi Germany,” he said, revealing that over the years it’s become harder to stay in touch with his family back in China. He has tried to distance himself “so they don’t get in trouble”, calling it a “price I have paid for my conscience”.

There’s no doubt that Tiananmen matters, whether it be a year ago, 20 years ago, 50 or 100. But it feels particularly relevant looking at the current Chinese landscape. Thirty-three years after students took to the square, the very same universities that they came from have erected fences in response to students protesting draconian Covid measures; in Shanghai, the lockdown has been so extreme that some people have jumped out of their own windows to their death. Traces of these recent events are being scrubbed from the internet as we speak. The path that the leaders chose when they sent the tanks in is one that we are still walking today, but it’s sadly narrower. Control is near absolute.

“No matter how rich, people can lose their freedom and be prisoners in their own home,” said Zhou. “They can be starved to death. Shanghai has amongst the highest house prices in the world but the government can use technology to control the people.”

And just like Tiananmen, we might never know how many people will have died as a result of the government’s ruthless Zero Covid policy.

“This is why Tiananmen is so important,” he added. “There’s no limit to what the government can do to violate human rights. It’s beyond the worst imagination.”

Zhou holds on to the one major positive that came out of the Tiananmen protests though.

“They demonstrated to the world that the Chinese people loved freedom. We were willing to fight for it and many people lost their lives for it. It showed the world what a different China could be. Today’s China is a nightmare. There could be a different China.’