Watching Season Five of Netflix’s lavish Windsor drama, The Crown, my phone was constantly in hand as, eyes flicking from screen to screen, I made cursory Google searches to decipher what was real and what wasn’t. Was Boris Yeltsin always drunk? Did Princess Anne eye her future husband through a pair of binoculars? Was Queen Elizabeth II’s morning read really The Racing Post?

One episode that really had my fingers typing away was episode five, The Way Ahead. This detailed the events from 1993 when the Sunday Mirror and Sunday People printed recordings of a phone conversation between the then-Prince of Wales and Camilla Parker-Bowles. Intercepted and recorded by an amateur radio enthusiast four years earlier, it arguably damaged Charles’ suitability claims as a future king and left Camilla vilified by the press.

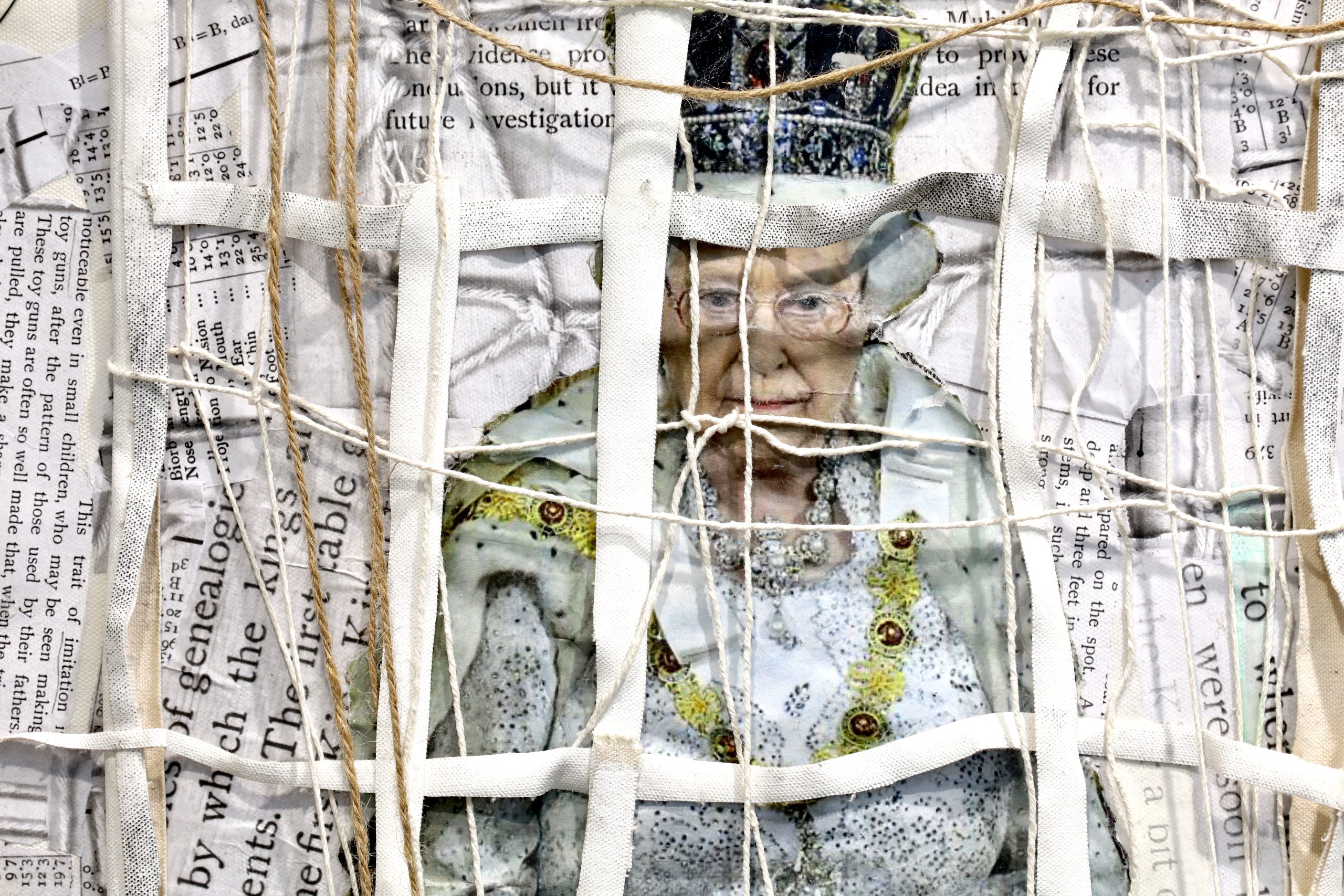

No criminal charges were pursued and while it wasn’t phone hacking per se, it was clearly an invasion of privacy, a level of which we should all be entitled to. However, as part of this Index investigation, I have been looking through Royal Family records at The National Archives and I can see an abuse of the concept of privacy. Archives that should quite firmly be in the public domain are not.

What’s striking is the absurdity, not only of the content but also the length of closure given, of some of the records. For example, a “public record” from 1936 was given access closure for 100 years. This record concerned offensive use of royal emblems in coronation decorations by a company called Dudley and Co Ltd.

What could possibly have been so offensive to justify this as a still-closed record? Was a lion on a Royal emblem too cartoonish? With fresh eyes in 2022, we should have the right to see.

There is also an interesting record from 1981 (like the above, it’s legal status as a public record) which is the year that Prince Charles married Diana Spencer. We obviously cannot see what’s inside. All we know is it’s called “News and publicity on the Royal Family”. Reconsideration of its blocked status was due in 2019 but there is no note that this happened.

A large number of documents on Edward VIII are blocked. A record from 1985-88 (some of the records only give a timeframe, not a specific year) states: “ROYAL FAMILY. Proposals relating to the papers concerning the abdication of King Edward VIII in 1936”. This is information regarding the abdication of a king that happened three years before The Wizard of Oz was released and when Queen Elizabeth II was 10 years old. As it concerns one of the biggest constitutional crises in the nation’s history, and one that occurred before most people were born, in whose interest is it to keep this public record closed? Interestingly, it has been retained by the Cabinet Office.

While Freedom of Information requests can be made on most of the records (the option isn’t available for the above 1985-88 record, for example), the extreme likelihood is that they will be denied. And believe us, we have tried.

The Royal Family has the right to privacy for things like intimate phone conversations, just like the rest of us. However, the extent of their grip on privacy disallows us access to their public records which, however banal and irrelevant they may be, we should have access to. The question must be asked: If there isn’t anything to hide, why are the records still closed?