Will Paulina ever rest?

by Jemimah Steinfeld, editor-in-chief, Index on Censorship

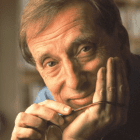

Celebrated Chilean-American playwright and author Ariel Dorfman yearns for the day his play, Death and the Maiden, is no longer relevant. Until then the play’s central character Paulina will continue to haunt him, and indeed us.

“She resonates magnificently, sorrowfully, accusingly, and will do so for, alas, a long time, until she can rest, until a day comes when spectators will leave the theatre asking: ‘Torture? What is torture? Can any society really have condoned such violence? It must be something the author invented’,” Dorfman told Index.

For the unacquainted, Death and the Maiden, which was originally published in Index and later turned into a film by Roman Polanski, follows Paulina Salas, a former political prisoner from an undetermined place, who was raped and tortured by her captors (led by a sadistic doctor). Years later, after the repressive regime has fallen, Paulina is convinced that she has finally found the man responsible and the story follows her quest for revenge.

But Paulina is not just a character from Death and the Maiden. She is now a character in The Embassy Murders, Ariel Dorfman’s new short story published exclusively here for the first time. So why does she keep on coming back? As Dorfman says, she’s never really left him since he conceived her back in 1990 because the situation that gave rise to her – justice unfulfilled – continues.

“If Chile had been able to afford her and so many others some justice once the dictatorship had been defeated, she would not have been forced to seek justice on her own and I would not have been forced to write the words she seemed to be dictating to me. But Chile, like most lands that have suffered terrible atrocities and need to move forward and not be trapped in the past, was unable to repair her wounds or assuage her grief,” he said.

Worst still, today in Chile Augusto Pinochet’s coup (which happened 50 years ago this September) and the resulting dictatorship is the subject of positive revisionism, said Dorfman. Rather than a consensus from left to right condemning his reign of terror, “extreme right-wing sectors, encouraged by recent electoral victories, have declared that they justify the military takeover — and many of them flirt with denial that such violations even occurred,” he said, adding:

“This position is extremely dangerous because of what these people are implying: if you ever try to change Chile again as you did in the Allende years, we will come after you again and this time, as the joke goes, “No more Mister Nice-Guy”. And this at a moment when the trust in democracy is eroding, both in Chile and all over the world.”

Dorfman said “it is up to the citizens of Chile to isolate those anti-democratic elements and make them irrelevant.”

The central plot of The Embassy Murders is compelling. It’s set between 1973, when 1,000 people are crammed into Santiago’s Argentinian Embassy seeking refuge for their role in resisting the coup, and the early 1990s, when Dorfman is wrestling with his return to Chile and what to do with literary characters that he has abandoned. He toys with the idea of penning a story about a psychopathic killer on the loose in the embassy in 1973. The result is “an embodiment of the metaverse, an alternative way in which certain events could have occurred in a parallel universe”, he said.

Dorfman himself sought refuge in the embassy in 1973, an experience that he unsurprisingly calls “unforgettable” and that he has written about in detail often. He has also visited the embassy since and tells Index of three particular times. In one, he went with the daughter of the young revolutionary Sergio Leiva, who had been shot and killed on 3 January 1974 by snipers from one of the adjacent apartment complexes. For him the anecdote “gives a sense of the dread we felt while we were there, how death surrounded us and finally targeted one of the refugees”. In another, when having dinner with his wife Angélica, he was amused when the ambassador’s wife asked if he needed directions to the bathroom.

“I laughed. ‘No, I went to that bathroom many times during weeks and weeks. Except on this occasion there will not be a line of 50 or 60 men waiting their turn outside’.”

A third visit, this year, saw him eat at the very spot he had once slept (under a billiard table).

“The exquisite meal our hosts prepared for us made the visit even more surreal because I had gone hungry often when I was in that embassy (not easy to feed 1,000 refugees),” he said.

Back to Paulina. Can she be put to rest? While Dorfman says there are Paulinas all over the world, at least when it comes to Chile people can try to ensure a reckoning with their own Paulinas.

“We just have to keep on telling the truth and hope that the seeds find fertile ground. My novel, The Suicide Museum, which inspired me to write The Embassy Murders story, has been my way of contributing to establishing that painful truth.”

Ariel Dorfman's latest book, The Suicide Museum, was published on 5 September 2023. Read more about it here