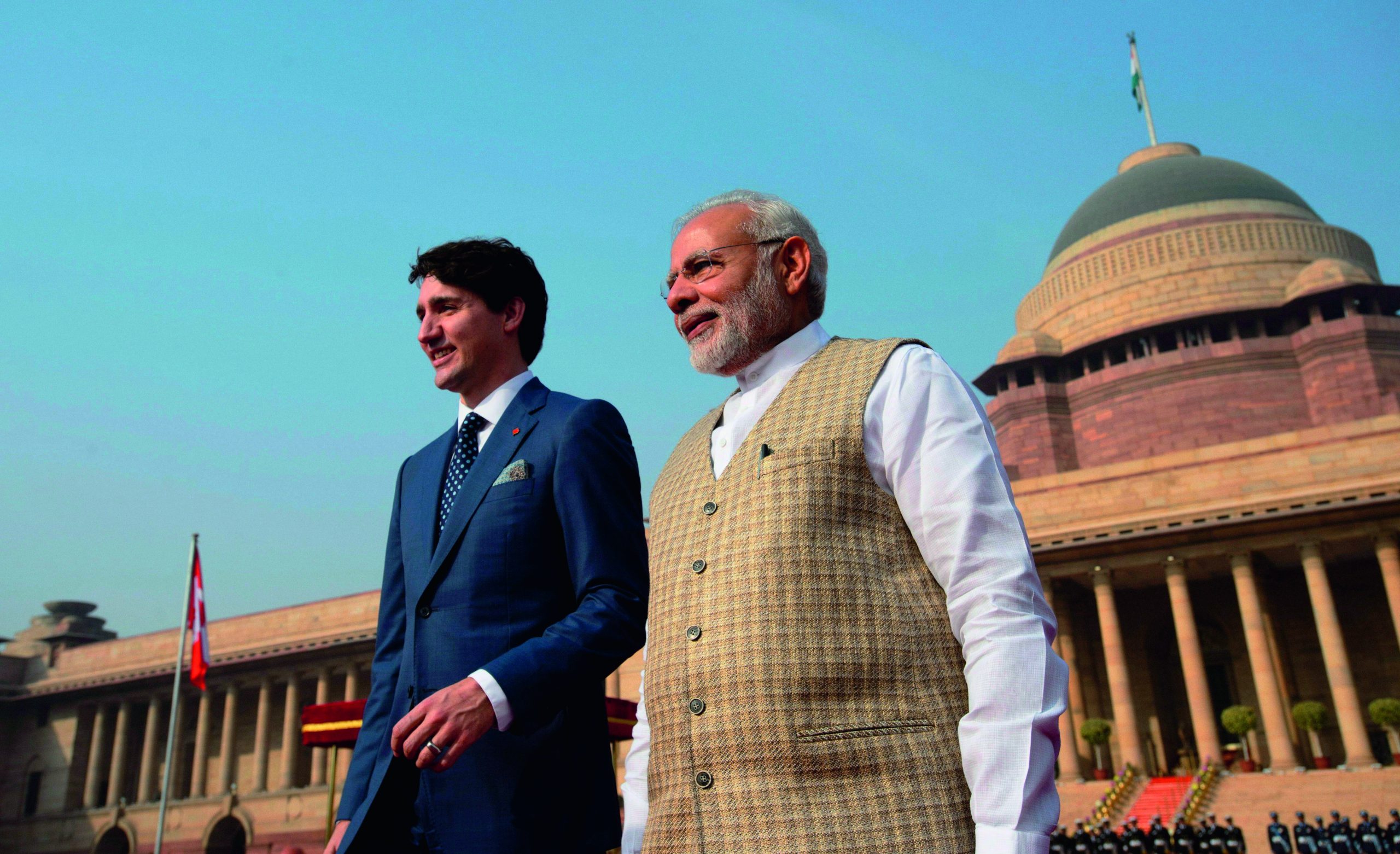

This article was first published in the Spring 2024 issue of Index on Censorship. We are republishing it here after Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau accused India of making a “horrific mistake” in violating Canadian sovereignty at an inquiry into the death of Hardeep Singh Nijjar.

Last June, Hardeep Singh Nijjar, a 45-year-old Sikh activist campaigning for Khalistan, a separate homeland for his co-religionists, was shot dead in British Columbia, Canada.

The murder happened in a car park, and a video emerged of his body collapsed over the steering wheel. Three months later, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau claimed there were “credible allegations” that the Indian government was involved in the murder. India reacted angrily, terming Trudeau’s charge “absurd”. India removed diplomats from Canada, asked Canada to reduce its diplomatic presence in India, and significantly delayed Canadian visa applications. The USA, Canada’s closest ally, expressed concern but did not say more.

In recent years, India’s strategic importance has increased for three reasons: its growing economy, its outwardly democratic credentials and its potential emergence as the counterweight to China – not only in Asia but on the international stage.

Western governments have been queuing up to invite Prime Minister Narendra Modi to visit their countries and rolling out the red carpet for him, or they’ve been visiting India and announcing investment deals – even if actual inflows may be puny compared with the bombastic claims.

Sikhs and India

Sikhs form about 2% of India’s population, and most of them live in the fertile and prosperous state of Punjab along with Hindus, Muslims and others. In the early-1970s, the Shiromani Akali Dal, a political party representing Sikh and Punjabi interests, passed a resolution seeking greater autonomy. By the late 1970s, a militant movement emerged, seeking an independent homeland called Khalistan, carved out of India.

Extremists representing Khalistani interests attacked government targets and terrorised civilians. Many militants garrisoned themselves in the holiest Sikh shrine, Amritsar’s Golden Temple, and in June 1984 then prime minister Indira Gandhi sent troops into the temple to eliminate the threat.

Hundreds died in what became known as Operation Bluestar. Four months later, on 31 October, Gandhi was assassinated by two of her bodyguards – both Sikh. In the retaliatory violence that followed, thousands of Sikhs were killed in northern India.

Indian security forces pursued the militants ruthlessly, and the Khalistan movement subsided. It survives among Sikhs abroad who dream of an independent Sikh nation, but in India there is little support for Sikh separatism.

However, Sikhs overseas and in India remember the attack on the Golden Temple, the pogrom of Sikhs in 1984 and the lack of justice. While Indian leaders have since expressed regret over the violence, and a Sikh economist – Manmohan Singh – was India’s prime minister from 2004 until 2014, the wounds have not healed. That accounts for the nostalgic longing for an independent homeland among some Sikhs abroad.

Nijjar’s killing would have remained largely forgotten, but in November the USA charged an Indian national, Nikhil Gupta, with attempting to hire an assassin to kill Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, a Sikh separatist leader who is the general counsel for Sikhs for Justice and who lives in the USA. Gupta, the USA alleged, was acting under the directions of an Indian government official and had offered $100,000 to a potential assassin.

He did not know that the man he was trying to hire was, in fact, a US agent, and Gupta is now in a Czech jail, awaiting extradition to the USA.

While the Indian government denied any role, its response to the US charge was more muted and less full of bluster than its response to Trudeau. US President Joe Biden was invited as the guest of honour to India’s day of pomp and glory – the Republic Day parade – in January this year. Biden did not make the trip and while he did not give any specific reason, diplomatic circles believe it was meant as a snub to India, which has elections later this year. The incumbent Modi would have loved the footage of Biden by his side, watching the might of India’s defence forces marching by.

There is no evidence of India’s role in either Nijjar’s murder or the plot against Pannun, and they could just as easily have been rogue operations. But the US charge-sheet is fairly detailed, and India’s subdued response raises questions. India’s current government has long admired the long reach of Israel’s Mossad, which has a record of carrying out spectacular attacks against those Israel considers its enemies.

Could some Indian officials have been tempted to imitate Israel as a form of flattery?

Transnational repression

Carrying out violent acts against individuals or organisations that a government considers hostile to its interests in a friendly country is an extreme form of transnational repression. But India has practised many other subtler forms of preventing contact between Indian dissidents seeking a global platform and foreign researchers or journalists wishing to report on India. It has expelled journalists, prevented academics from entering the country, stopped its own journalists or human rights activists from travel and got Indian embassies to complain loudly against foreign reporting of India.

Most recently, Vanessa Dougnac, who had been the longest-staying foreign correspondent in India, said she would leave the country after India revoked her status as an Overseas Citizen of India (OCI). (She is married to an Indian national, and so qualifies for such a status.) The title is misleading: OCI does not grant any citizenship rights such as the right to vote, but it grants the individual a permanent, long-stay visa and the ability to work (except in certain sectors). Dougnac was told her reporting for various French publications created a “biased, negative” perception of India. She wrote a heartfelt lament while leaving the country she considers her own, saying the government’s onerous conditions made it impossible for her to work there.

Earlier, the overseas citizenship of Ashok Swain, who teaches peace and conflict studies at Uppsala University in Sweden, was revoked. In November 2020, Swain was informed his OCI would be revoked because of his “inflammatory speeches” and “anti-India activities”. Swain asked for specific instances and requested for the decision to be overturned so he could visit his unwell mother back in India. His request was denied.

Swain sued the government, and in July 2023 the court ruled in his favour, saying the government needed to provide proper reasons. Later that month, the Indian embassy in Stockholm sent him another note, long on rhetoric and short on specifics, saying he was “hurting religious sentiments”, “destabilising” India’s social fabric and “spreading hate propaganda”. Swain was tweeting too much and too critically about India, the order said, hurting the country’s image abroad. Swain’s case will be heard in May.

The OCI status was created not as a right but as a privilege or an entitlement, because people of Indian origin who lived abroad had been clamouring for dual nationality, which Indian laws don’t permit. It was created in 2005 under the 1955 Citizenship Act, which allows foreign citizens of Indian origin or foreigners married to Indian citizens to enter the country without a visa and reside, work and hold property there, among other benefits.

But lately the government is wary of OCI journalists and academics visiting or living in the country, especially if the government does not like their reporting or investigations. In March 2021, India required OCIs to seek a permit to conduct research, for mountaineering, for missionary, journalistic or Tablighi (a Muslim sect) activities, or to visit any area of India deemed as “protected”.

According to the human rights and law-focused web portal Article 14, which has examined the issue in great detail, more than 4.5 million people around the world are OCIs, and data released by the government in response to an inquiry under India’s Right to Information Act, showed that the Modi administration had cancelled at least 102 OCI cards between 2014 and May 2023. In theory, those whose OCIs are cancelled can apply for a regular visa to visit India, but the government reserves the right to blacklist them which would, in effect, bar them forever from entering the country.

In November 2022, 82-year-old UK-based activist Amrit Wilson received a letter that tore to shreds her official ties with India. The letter, from the Indian high commission, blamed her for “anti-India activities” and for making “detrimental propaganda” which was “inimical” to India’s sovereignty and integrity. There was, of course, no evidence – but she was asked to provide reasons within a fortnight why her status should not be revoked. Wilson sent a detailed response, but several months later the government replied that her response wasn’t “plausible”, and cancelled her status. She is now appealing through the Indian court system. In its response, the government pointed out some of her tweets for being critical of the government and an article that opposed the revoking of the special status granted to the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir.

The government claims it can cancel the status of those who have shown “disaffection to the constitution” or “assisted an enemy during war”, or done anything that it believes is against the interests of “sovereignty, integrity and security” of India.

Chetan Ahimsa (Kumar), a leading actor in Kannada films, had his status revoked briefly, too. Ahimsa is a US citizen. He was arrested in India after he criticised a ban on Muslim students wearing the hijab in schools in the southern state of Karnataka. In court, the government said India could expel people who were “undesirable” and foreigners did not have the right to free speech in India. The court stayed the cancellation.

More famously, in 2019, the USA-based writer Aatish Taseer, whose mother is the Indian journalist Tavleen Singh and whose father is the slain Pakistani politician Salman Taseer, had his overseas citizenship cancelled after he wrote a cover story in Time magazine asking if India could survive another five years of Modi.

In Taseer’s case, the government claimed his status was revoked because he had “concealed” the fact that his father was a Pakistani national. Earlier, in 2014, Christine Mehta, a researcher at Amnesty International, had her OCI revoked after she studied India’s human rights record in Jammu and Kashmir.

A gigantic conspiracy?

A web-based portal called Disinfo Lab has, according to a report in The Washington Post, been compiling information of critics overseas, Indian or not, and blaming them for undermining India. The portal establishes links between the critics and the philanthropic billionaire George Soros, sometimes by connecting disconnected dots, to present an image of a gigantic conspiracy.

At the same time, foreign-based web portals critical of India are being taken offline inside the country. The latest to suffer such erasure is Hindutva Watch, which compiled human rights violations by Hindu fundamentalists. India has escalated demands on X, formerly Twitter, and many accounts critical of the government have been “withheld” recently, including those operated by foreigners who live abroad. X has complied, but issued a statement expressing disapproval of the government’s action. Clearly, X’s owner Elon Musk, who claims to champion free speech, has a different standard for different countries, and in the Indian case, he has meekly complied with many requests.

Academics are also being turned away. Within weeks of Modi’s election in 2014, Penny Vera-Sanso, of Birkbeck University in London, who had been visiting India since 1990 and writes about gender, was denied entry. In 2022, Lindsay Bremner, who teaches architecture at the University of Westminster, had a valid research visa when she arrived in India, but was told at the airport that she could not enter. Earlier that year, Flippo Osella, who teaches anthropology at the University of Sussex, was sent back. He is an expert on Kerala and has been visiting India for 30 years. The government claimed his research on caste was deemed “sensitive”. Osella understands Malayalam and has studied the Ezhava community. He has written about Mamootty, a popular actor in Kerala, and was working with local institutions on predicting weather. His research was supported by the UK government, but he was treated brusquely and not allowed to contact friends in India.

India has also barred writers and academics who have tourist visas but who might conduct research, which would technically violate Indian rules. In 2018, Kathryn Hummel, an Australian poet, was turned away at Bangalore airport and Pakistani researcher Annie Zaman was similarly sent back and prevented from attending a conference in Delhi. When I sought out some of the academics denied entry, none of them wanted to speak, on or off the record, because they did not wish to jeopardise their visas in the future. Some American journalists, Indian origin or otherwise, too have had visa requests delayed or denied.

When graduate students and academics at several US universities organised a three-day conference in 2021 called Dismantling Global Hindutva, which examined the rise of Hindu nationalism in India and its effects on Indian society, several academics and potential speakers were warned off from participating, and a few backed out, so as not to jeopardise future visits to India. Indian residents in the USA who support the Indian government wrote to faculty heads and university administrators complaining against those academics. Academics in the USA who are of Indian origin and are critical of India have frequently been targeted by concerted efforts from pro-government overseas Indians, calling for their dismissal or for them to be disciplined.

Several journalists and human rights activists living in India find themselves mired in legal cases, which means they must have clearance from courts or other appropriate authorities before leaving the country. This has prevented several writers and human rights activists from participating at events overseas.

Others with clean records also find that they are suspect. Sanna Irshad Mattoo, a Kashmiri photojournalist whose photographs earned her the Pulitzer Prize in 2022, was prevented from leaving for Paris to launch a book featuring her work, even though she had a valid French visa.

India is erecting a barrier between scholars and their subjects, reporters and their stories, and closing off doors and windows, narrowing Indian minds and hardening outlooks.

And it flexes its muscles abroad, shouting at critics, preventing their travel and access, and – if the Canadian and US accusations are true – attempting to eliminate those it disagrees with.

But it will hold elections in a few months, and encomiums praising the world’s largest democracy will follow. Naturally.