Do you want war or peace? That is the message plastered across billboards, bus stops, buildings and even vans in Georgia’s capital Tbilisi. Next to the words is a compare and contrast – devastating scenes from Ukraine, with 4, 5, 9 and 25 crossed out in the corner, against pictures of intact Georgian roads with 41 on top. Forty-one is the number of the current ruling party in Georgia, the Georgian Dream. The other numbers belong to the main opposition parties. The message isn’t exactly subtle. Vote for opposition when the country goes to the polls on 26 October and Russia invades; vote for Georgian Dream and peace remains.

Peace perhaps, but freedoms? Less so.

After spending three days in Tbilisi earlier this month as part of a Council of Europe mission – and speaking to journalists, activists, diplomats, politicians and people from various government bodies – the overriding impression is that the rights landscape is in freefall and much of that is because of Georgian Dream.

Georgia has made international headlines several times this year and all for bad reasons. The first instance was in the spring when the government passed legislation called the “transparency of foreign influence” law (often dubbed the foreign agents law, or by opponents, the Russia law). Under it, media and non-governmental organisations that receive more than 20% of their funding from abroad have to register as “organisations acting in the interest of a foreign power” and must meet onerous disclosure requirements, or face punitive fines.

The law drew sharp criticism from people both within and outside of Georgia, who saw in it an attempt to crush dissent ahead of the elections and remodel the country along Kremlin lines. Tens of thousands took to the streets to protest in some of the largest demonstrations since the country gained independence from Moscow in 1991. They were met with violence. Georgia’s President Salome Zourabichvili, who opposes the government, also vetoed it. None of this mattered. It was signed into law on 3 June.

Last month the “Family Values Bill” was introduced, which is part of a package of bills under the heading of “On Family Values and Protection of Minors”. Don’t be fooled by the wording. The package intends to promote a heteronormative, traditional lifestyle and silence anyone who doesn’t fit that mould. It provides a legal basis for authorities to ban gender transition, nullify same-sex marriages conducted abroad, ban adoption by gay and transgender people, outlaw Pride events and public displays of the LGBTQ rainbow flag, and impose censorship of films and books – amongst other measures. It has been met with opposition. Again, opposition was ignored. The bill was signed into law on 3 October.

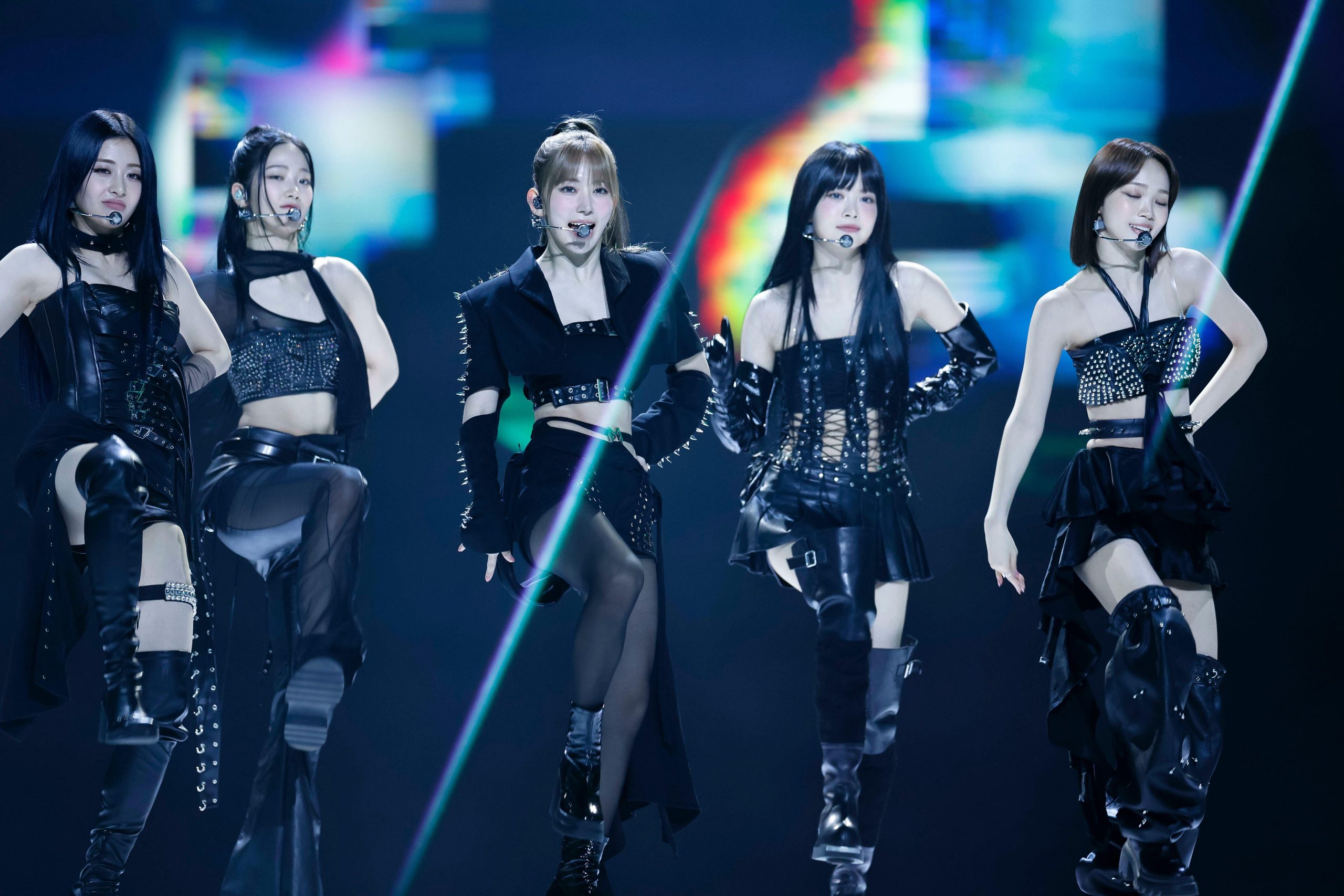

Billboards in Tbilisi, Georgia. Photo by Jemimah Steinfeld

When we sat down with a representative from the Georgian Dream, who was very insistent that international NGOs such as Index should not get their facts wrong, I posed a simple, hypothetical question – if material related to LGBTQ themes was removed from universities, would a journalist reporting on the story risk falling foul of the new law? After obfuscation and evasion, he conceded – yes, the journalist would risk that. So, two groups silenced in one move – the LGBTQ community and reporters.

Those working within the media and for NGOs are fearful and emotionally drained. They are being harassed, threatened, arrested, beaten, and having their offices vandalised. They are being taken to court on spurious defamation charges. Crimes are going unpunished, while attempts to access public information are often frustrated or denied, which includes information on the elections themselves. Last month Transparency International Georgia was banned from observing them following a decision by the Anti-Corruption Bureau to classify the international NGO as an entity “with a declared electoral goal” (it is nothing of the sort). Fortunately in this instance the ban was removed following outcry from civil society and opposition politicians. Who remains on the list though?

In reference to the media specifically, a diplomat said they are in survival mode. These words were echoed later when we heard first-person testimony from a reporter critical of the ruling party who has been arrested, whose house exterior has been branded with posters calling him a foreign agent, whose car has been shot at. He takes a chaperone to assignments as a form of protection. His greatest wish today is that he survives the election lead-up unharmed and out of prison.

It wasn’t always like this. Until recently Georgia was held up as one of the more successful countries from the post-Soviet bloc in terms of democratic rights. The Georgian Dream, which has been in power since 2012, started with democratic and reformist aspirations and Georgia was a destination for those seeking refuge from autocratic neighbours. Not so now, as the example of Azerbaijani journalist Afgan Sadygov shows. He was arrested this summer at Tbilisi airport and is currently in detention. If he is extradited to Azerbaijan he will likely be sent straight to jail. We spoke to his wife, Sevinj Sadygova. She had little faith that the current government would reverse her husband’s fate.

Still, all is not lost. The fact that we could conduct this mission and were interviewed on Georgian TV about our findings at the end of it shows some space for dissent remains. That we met with many remarkable people who are dedicated to upholding freedoms shows that their spirit is not yet crushed. But the concern that Georgia is on a path to become the next Belarus, another Russian proxy, is high and it’s easy to see why. Just walk down any street of Tbilisi. You might occasionally see a poster from an opposition party (I did). It’s just their message is being drowned in a sea of posters all brandishing the same number – 41.

Jemimah Steinfeld was invited to Tbilisi, Georgia by the Council of Europe, alongside other free speech and human rights organisations.