This article first appeared in Volume 53, Issue 4 of our print edition of Index on Censorship, titled Unsung Heroes: How musicians are raising their voices against oppression. Read more about the issue here. The issue was published on 12 December 2024.

Big technology companies have enormous and outsized power. They control what information we can share and how, and demonstrate little transparency or accountability to users about what they are doing. They are too often permitted to set their own arbitrary standards, governing what we can and can’t say on social media, and how and to whom these ever-shifting rules apply. In no area is this more evident than in the battle between those who want to seek out and criminalise women for having an abortion and those who want to protect women’s right to choose.

In recent years, technology has dramatically altered the abortion landscape for women in the USA. It is now possible to order safe and effective abortion pills online and find accurate information about how to use those pills. This represents an unprecedented and world-changing expansion of women’s privacy and freedom. Thanks to improved access to medication, far fewer women will die or be traumatised, despite the US Supreme Court’s 2022 decision to strip the country’s women of federally guaranteed abortion rights. But women’s new-found abortion freedoms are under threat from powerful people who oppose privacy, freedom and safety for women, and corporatists who put business interests above human rights.

With President Donald Trump’s re-election things may be about to become a whole lot worse.

In March 2024, eight months before the election, I attended Visions for a Digital Future: Combating Online Suppression of Abortion Information, a panel discussion hosted by a coalition of rights and safe abortion access organisations including Amnesty International USA, Plan C, the Universal Access Project and Women on Web, along with experts from Le Centre ODAS and Fòs Feminista.

The panellists warned that tech companies were already suppressing information about reproductive health, either deliberately and as a matter of policy, or accidentally, such as when posts containing legitimate medical information trigger filters meant to block other kinds of content. Remedies have been piecemeal. Some organisations have been able to get accounts reinstated after meeting with contacts at Meta, but there is no democratic and transparent way of determining who gets access to vital medical information.

In one very recent case, Meta temporarily shut down the advertising account of Plan C, a group that provides up-to-date information on how US residents access abortion pills online, days before the US election, over claims of “inauthentic behaviour”.

European lawmakers have already taken steps to bring Big Tech companies to heel. They have done so via laws like the EU’s Digital Markets Act, a 2022 law which, among other things, requires large tech companies to get users’ consent before tracking them for advertising purposes; and the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA), which went into effect earlier this year, preventing large online platforms such as Facebook, X and Instagram from arbitrarily restricting or deleting independent media content.

Despite growing pressure from large parts of civil society, the USA has yet to pass federal legislation to meaningfully regulate Big Tech. Under a Trump presidency, the federal government is likely to go one step further and ask tech companies to use the data they hold to assist state and local law enforcement in tracking, prosecuting and jailing women for seeking abortions.

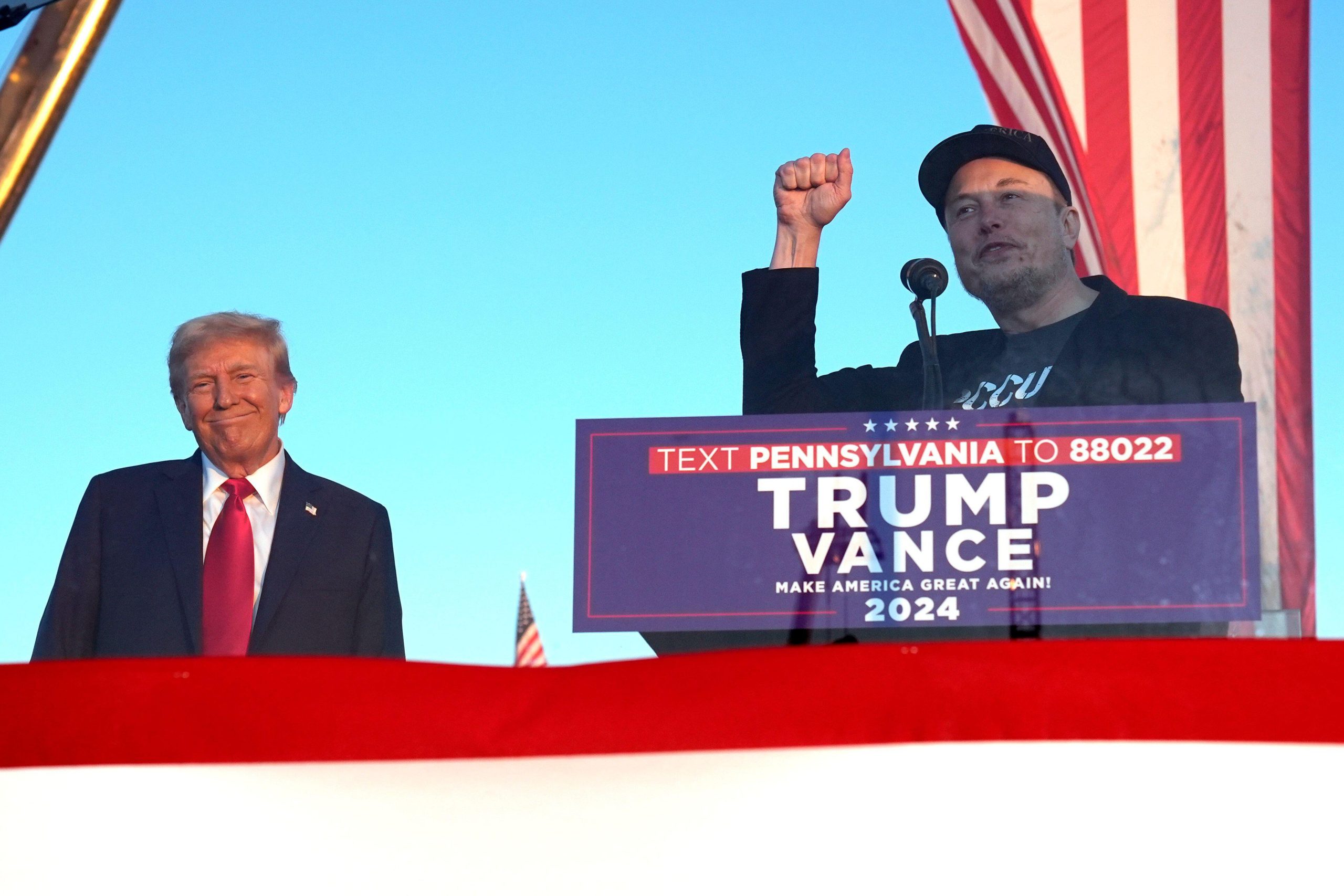

Some of the president-elect’s most prominent supporters are anti-feminist tech executives like Elon Musk, the richest man in the world and an ardent foe of government regulation (of corporations); venture capitalist Peter Thiel, who has questioned the wisdom of ever allowing women to vote; and Blake Masters, failed congressional candidate and chief operations officer of Thiel Capital (Thiel’s venture capital investment firm). All three have either previously expressed personal support for at least some level of abortion restriction or given large sums of money to politicians committed to restricting it.

Knowing it was a liability for him, Trump made confusing and contradictory statements about abortion on the campaign trail: once pro-choice, he bragged about having appointed the Supreme Court justices who overturned Roe v Wade.

By contrast, Vice President-elect JD Vance is an open theocrat who has pressured federal regulators to rescind a Biden administration rule that prevents police from accessing the private medical records of women who cross state lines to get reproductive health care, according to investigative news outlet The Lever.

Project 2025, the 900-plus-page handbook assembled by the right- wing Heritage Foundation and drafted in part by dozens of former Trump administration officials, indicates that a second Trump administration will seek to increase federal surveillance of pregnant people nationwide. They will most likely do this partly by requiring states to report abortion data and cutting federal funding to those that don’t comply. That data could put women and health care providers in serious danger of prosecution and/ or jail time. State law enforcement officials could pressure or compel tech companies to collect and share it.

This has already happened in the USA under a Democratic administration. Facebook’s 2022 decision to comply with a Nebraska police officer’s request for private data enabled the state to try, as an adult, a 17-year-old girl facing criminal charges for ending a pregnancy. Facebook handed over private messages the girl and her mother had exchanged in which the two discussed obtaining abortion pills, according to The Guardian.

The extent of the data Facebook handed over is unclear, but it’s apparent that companies like Facebook’s parent company Meta cannot be trusted to safeguard users’ privacy. Many of the largest tech companies in the world have refused to clarify how they will handle law enforcement requests for abortion-related data. While Meta does not allow users to gift or sell pharmaceuticals on its platform, it does, in theory, allow them to share information about how to access abortion pills, although enforcement of that policy has been inconsistent and non-transparent.

One ray of hope is that there’s a small chance that Trump will retain Lina Khan, Biden’s pick for chair of the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Khan has advocated for restraining the tech industry’s power and is seen as a threat. Days before the election, Musk wrote on X that Khan “will be fired soon.” Yet Vance has defended Khan, saying in a recent television interview that “she’s been very smart about trying to go after some of these big tech companies that monopolise what we’re allowed to say in our own country.”

Best known as an anti-monopolist, Khan has brought lawsuits against data brokers trafficking in geolocation data, a crucial bulwark against efforts by anti-abortion prosecutors to obtain women’s private medical data. This is important because in 2023, 19 Republican attorneys general in states that criminalised abortion demanded access to women’s private medical records in order to determine whether they had travelled out of state for care.

Under Khan, the FTC also cracked down on companies that extracted and misused customers’ private data. Browsing and location data of the kind these companies were gathering can provide intimate details of a person’s life, from their religious and political affiliations and sexual proclivities to their private medical decisions. Companies, knowing that most people would object to having this kind of data collected and shared, often hide what they are doing or mislead users about the extent of it.

It’s not yet clear what Trump’s top priorities will be as president, or who will have his ear. On the question of Khan, it seems likelier that he’ll take his cues from an oligarch like Musk than from his own vice president. As Politico recently noted Vance will have “little agenda-setting power of his own” in the new administration. Occasional anti-Big Tech rhetoric notwithstanding, neither Trump nor Vance cares about protecting women’s privacy. If Khan is fired, it’s extremely unlikely that any member of the Trump administration will take measures to safeguard medical data. State and local authorities will have to do everything in their power to pressure or require these companies to clarify why they are suppressing abortion-related content, and push them to fight requests that violate users’ privacy in court.

Authorities should also push or force tech companies to take measures – such as not collecting certain data in the first place or making it more secure – that would make it difficult or impossible to comply with law enforcement requests designed to punish women for exercising a right recognised by most Americans and international law. Failure to do so will jeopardise women’s lives, health and freedom.