Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

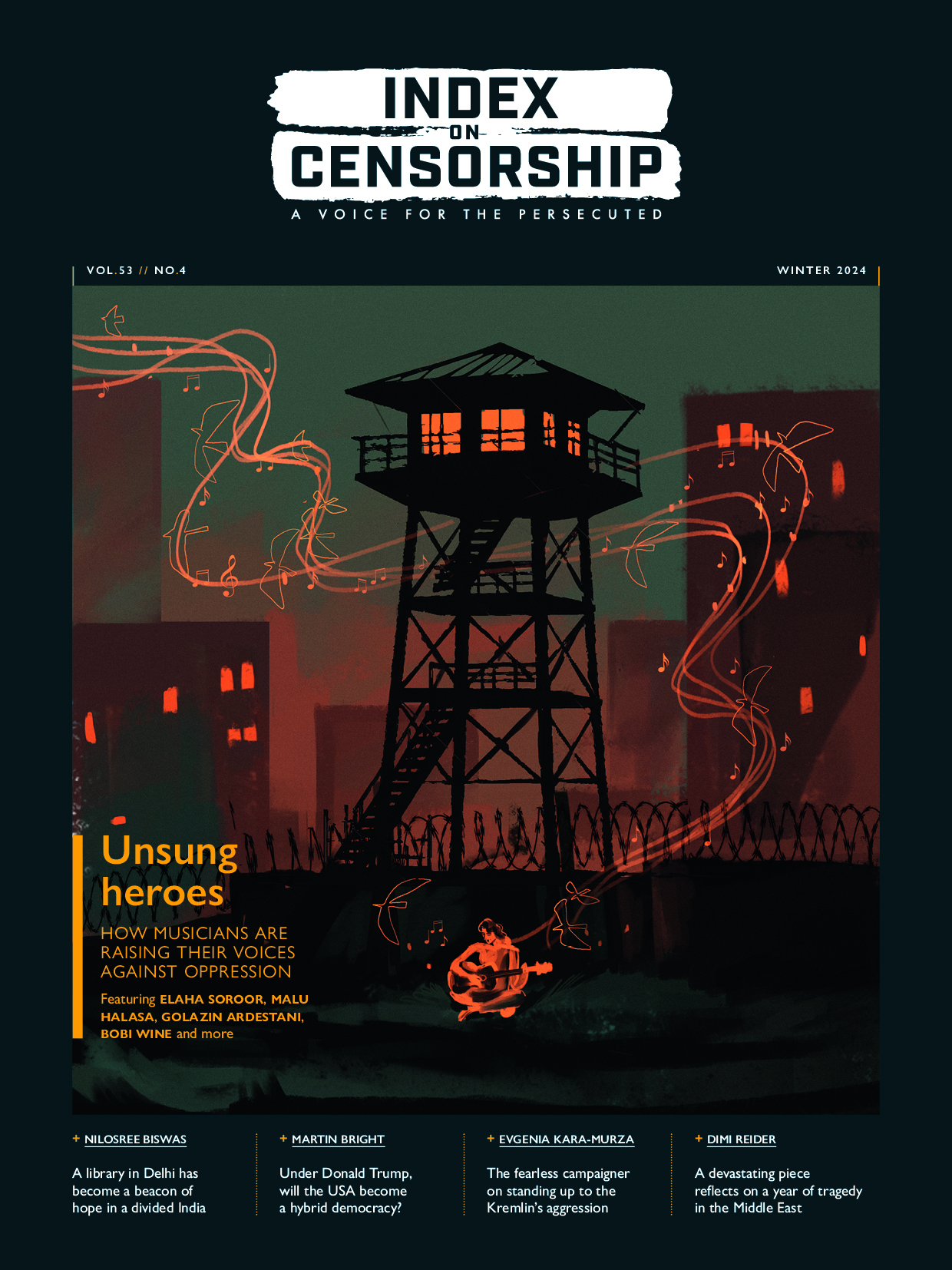

This article first appeared in Volume 53, Issue 4 of our print edition of Index on Censorship, titled Unsung Heroes: How musicians are raising their voices against oppression. Read more about the issue here. The issue was published on 12 December 2024.

A black square was all it took. Veteran journalist Kyaw Min Swe was arrested by the Myanmar military junta in April 2023 after he blacked out his personal Facebook profile – a sign of despair at the bombing of Pazigyi, a village near his hometown in the Sagaing region, which killed more than 100 people including children.

Around 300 people had gathered for the opening of an office of the National Unity government in exile. Eyewitnesses reported that a fighter jet bombed the village before a helicopter fired on those escaping. It was one of the deadliest attacks on civilians since the military coup in 2021.

Kyaw, the former editor-in-chief of weekly newspaper Aasan (The Voice) and executive director of the Myanmar Journalism Institute, has been a journalist for more than 25 years. He had been detained before, but this time was different.

“On a popular Telegram account that monitors high-profile people like me, I was accused of supporting the People’s Defence Force [the PDF is the military wing of the exiled government] and opposing the military with that Facebook post,” he told Index. He was summoned to the military interrogation centre in Yangon to explain himself.

“I had nine days of torture – not physical, but mental: three interrogators, working in rotation, asking me the same questions and depriving me of sleep.

“They lied about arresting my reporters, pretending they had evidence of connections with the exiled government and the PDF, but they had nothing. I simply told them the truth: I’m a professional journalist, not pro-exiled government or anti-military, but I disagree with the coup.”

Later, he was bundled into a vehicle with a bag over his head.

“I was scared. This was different to my previous experiences,” said Kyaw, who was taken first to the police interrogation centre and then to Sanchaung Township police station, where he was charged under Section 505A of Myanmar’s Penal Code – used by the junta to target those seen to criticise the regime and carrying a maximum three-year prison sentence.

After almost three months, including two spent in chains in the notorious Insein Prison, he was finally released – with an order to report weekly to police.

“From then on, I was monitored constantly,” he said. “The military actually offered me financial support, but they wanted to use me as propaganda and I knew that was professional suicide.”

While detained, Kyaw decided he and his family needed to leave Myanmar.

“It was no longer the right place for my kids,” he said.

He contacted a friend at Deutsche Welle, the German state broadcaster which part-funds the Myanmar Journalism Institute, and last October he fled Yangon under cover of darkness with his wife and two children.

The daring escape to Germany via Thailand included crossing rivers, trekking through jungles, climbing walls and sheltering in safe houses. Eight months later, with the help of the Exile Hub, an independent organisation based in Thailand, they finally found safety in Berlin in June 2024.

“For my kids it was like an adventure, but not for my wife, who spent seven months taking Xanax because she couldn’t sleep,” said Kyaw. “She was anxious every time she saw someone in a uniform. In Myanmar, she’d got used to hiding my laptop in the washing machine every time the doorbell rang.”

Over the course of his career in Myanmar, Kyaw has seen censorship fluctuate between brief periods of hope and progress to crushing repression.

Before 2011, the military junta imposed strict censorship on the press. Independent media was non-existent, with most newspapers being government-owned or strictly controlled, focusing on state propaganda. Kyaw’s media house, for example, was owned by the son of the military intelligence chief.

Journalists had to submit their work to the Press Scrutiny and Registration Division (PSRD) before publication, and any critical or sensitive content – particularly related to the military, politics or ethnic conflicts – was censored. Kyaw said his magazine was suspended six times, sometimes for infringements as minor as running adverts that mentioned neighbouring Thailand.

With the shift to a quasi-civilian government under president Thein Sein in 2011, Myanmar experienced a brief period of media liberalisation. As secretary at Myanmar’s Press Council, Kyaw helped draft a media law to protect journalists. The PSRD was abolished, private newspapers were allowed to publish daily, and journalists, for the first time, began to report on previously forbidden subjects.

Yet they still faced threats and prosecution. Kyaw was sued for defamation by the Ministry of Mines in 2012 for publishing a story about alleged misuse of public funds, based on a report from the parliamentary watchdog.

“The ministry demanded a front-page apology, but the parliament report was so clear, we politely declined,” he said.

The case dragged on for months and Kyaw faced dozens of court appearances before it was dropped, following pressure from human rights NGOs and a ministerial reshuffle. Kyaw took this as a sign of progress.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) came to power in 2016, but the military retained significant power and media freedom deteriorated again.

“We expected a lot from the NLD,” recalled Kyaw. “We self-censored and hesitated to criticise them because people loved them so much. We didn’t want to be labelled pro-military.”

Several high-profile cases of media repression occurred, notably the jailing of Reuters journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo for reporting military atrocities against the Rohingya.

In 2017, Kyaw was arrested in his newsroom along with columnist Ko Kyaw Zwa Naing after a military official complained about a satirical article published in response to a film commemorating Armed Forces Day. Charges against Ko Kyaw Zwa Naing were dropped, but Kyaw Min Swe remained in Insein Prison for two months, on trial for “online defamation’’ under the 2013 Telecommunications Law.

“They treated us decently because the international community was watching,” Kyaw recalled. “The military, and even the Press Council, wanted me to apologise, but I said, ‘I’m sorry, this is satire, a form of art. If I apologise, my career is gone’.”

The military coup of 2021 dramatically reversed any media freedoms that had been gained. The military seized control of all state media, revoking the licences of independent news outlets such as Mizzima, Myanmar Now and DVB.

“Every journalist was watched and monitored,” Kyaw said. “Many journalists were arrested, others were beaten at demonstrations on the street.”

Draconian laws were passed, including Section 505(A) of the Penal Code which criminalises “causing fear, spreading false news, or agitating against government employees”. Kyaw’s newspaper was forced to cease publishing when businesses switched their advertising to state-owned media.

Myanmar has become the world’s second biggest jailer of journalists, second only to China, according to Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

Several “exiled media” outlets such as The Irrawaddy have relocated to Thailand and rely on citizen journalists to provide content. Kyaw said he hoped bodies such as the Myanmar Journalism Institute might act as platforms to attract funding for exiled media, as well as for journalists still working inside the country for regional or ethnic media houses. But this can also be problematic.

“Some [exiled] Myanmar media report only what’s happening in the war, and only when it’s good news for the PDF and the exiled government. But Myanmar people have a right to know true information, free of bias, about the war, the economy or even natural disasters that are happening,” Kyaw said.

“Without that reporting, our people cannot prepare for the future.”

This article was updated on 6 February 2025 to clarify that Exile Hub is an independent organisation based in Thailand.

This article first appeared in Volume 53, Issue 4 of our print edition of Index on Censorship, titled Unsung Heroes: How musicians are raising their voices against oppression. Read more about the issue here. The issue was published on 12 December 2024.

The recent passing of One Direction’s Liam Payne made me reflect on my first encounter with him during the filming of The X Factor in the autumn of 2010. The confident 17-year-old from Wolverhampton enthusiastically posed for pictures with my daughter before delivering a note-perfect performance on the show that night. There was no doubt in my mind that he had a golden career ahead of him.

In the spring of 2012, I found myself in a small, windowless room in the bowels of Cardiff City Football Club judging the first round of potential contestants for that year’s competition. During the day, I sat with an assistant producer on the show and ate a large jar of Haribo as we auditioned countless hopefuls. By the early evening, I never wanted to hear Rolling In the Deep again. A pain in my right shoulder had spread down my body and I felt like I was seizing up. When I saw the doctor the following day, she asked what my lifestyle was like. I explained that I had been to the USA twice that month, worked most evenings and drank coffee to power through the days.

“I can see it in your eyes,” she told me. “They are dull, you have no energy, the fire in your soul is out.” She prescribed immediate bed-rest and suggested I read The Presence Process by Michael Brown, a spiritual manual encouraging being present in the moment. I followed her advice, took some time off work and read the book. Four weeks later, I left my job running Columbia Records in the UK.

I had been working flat out in the music business for 25 years and was suffering from acute work-related stress, coming close to physical collapse. And yet I was incapable of doing anything about it until my body intervened on my behalf. As the head of a record label, I hadn’t recognised the symptoms of exhaustion and mental ill health in myself, and yet I was responsible for the wellbeing of both my staff and the artists on the roster.

My story was not uncommon in the music industry at the time. Whilst shows such as The X Factor had a duty of care to the contestants and employed a psychiatrist to help anyone with potential problems, the pressures on anyone following a career on the front line of popular music can very easily become too much to bear. The business frequently turned a blind eye to mental illness. If the talent could turn up and deliver then it wasn’t a problem. Signing a record deal with a major label can feel like answered prayers. Everything an act has worked towards has brought them to this point and finally they can devote their lives to making music.

No matter how much you anticipate making it in the music business, however, nothing can prepare you for the impact of fame. As Blur’s bass player Alex James put it recently: “Success will fuck you up far more than failure.”

The demands on the time of a successful artist are huge, and they are often on the go from early morning until the middle of the night if they are performing live or working in the studio. As a creative professional, they also carry the burden of relying upon their talent – which has got them this far – to take them to the next level. Their every move is being publicly scrutinised and any private life has evaporated. It is no surprise, then, that musicians frequently resort to stimulants to help them through the day, brimming with confidence, only to need something else to help them go to sleep. It is a potent and sometimes deadly cocktail.

The worst part is that you are supposed to be living the dream and any suggestion that your life is anything less than perfect feels like letting people down. For too long, the music industry ignored the pressures of work for artists and those behind the scenes across the business.

By 2017, I was running a major music publishing company and had a much better understanding of mental health than I had five years earlier. I was shocked to discover that a substantial proportion of our songwriters were suffering with psychological problems which prevented them from working. The stress of being able to consistently deliver hit songs takes an enormous toll and many writers simply couldn’t find a way forward. From that point onwards, we made the decision to include in our songwriter contracts a provision to access professional mental health care. The staff at the company were taught about the importance of looking after their own wellbeing and they had access to full healthcare if it was needed. We formed close relationships with mental health charities such as Music Support.

The music business in 2024 is very different from the one I joined in the mid-eighties and it has made huge strides in the field of mental health over the past 10 years. All the major music companies have professionals on the payroll, working with their staff and their artists. Particular attention is paid to young artists at the beginning of their careers as well as to those that are exiting the company and facing an uncertain future. There is a clear understanding of the need for personal time and breaks in the schedule to rest and recuperate. The brutal schedules of the past have been moderated. I am optimistic for the future as the new generation of executives coming through have a much greater understanding of wellbeing than I did when I was younger.

As a result, the artists and musicians in their care are finding themselves in a much kinder and safer environment. But sadly, it seems it was all too late for Liam Payne.

Index on Censorship launches the latest issue of its magazine with a powerful night of poetry and music

Yoweri Museveni’s most formidable challenger refuses to be silenced and remains on the frontline of protest

The police are disproportionately censoring and criminalising music by young Black men, with drill at the forefront

Contents

Musician faces death sentence after three years of judicial harassment, including arrest, imprisonment and torture

Musician's inclusion of women's voices in his last album has led to his arrest. Here he talks exclusively to Index on Censorship about the challenges

Belarusians began 2025 in a state of anxiety. It’s nothing we haven’t seen before – another presidential “election” is approaching, or rather, another dictatorial re-election. There hasn’t been a free and fair electoral process in our country for decades, so it’s not as though we don’t already know the outcome: over 80% for Lukashenka, written in by the Central Electoral Committee.

The atmosphere is tense. Ever since the protest movement began in response to the fraudulent 2020 election, we haven’t experienced peace. Lukashenka took Belarusians’ pro-democratic aspirations personally (as he should) and hasn’t stopped his relentless repression for a single day. There are more than 1,300 political prisoners, with thousands more having already served their unjust, politically-motivated sentences. The leaders of our resistance are held completely incommunicado behind bars, and the only way we know they’re alive is when the regime uses them for propaganda. Maria Kalesnikava, Viktar Babaryka, Ihar Losik – they’re dragged from their cells, dusted off and paraded in front of cameras for twisted manipulations. Yet their dignity and strength remain unbreakable, fuelling our anger and disgust toward their captors.

As the election draws closer, the regime continues its threats. Apart from ongoing mass detentions – many still related to participating in the 2020 protests – Lukashenka announced last month that any public resistance during the “election” on 26 January will be met with a complete internet shutdown. Terrible? Yes. New or shocking? No.

About two weeks before the election, Belarusian independent media outlet Motolko Help reported that access to YouTube, Telegram and Discord was temporarily blocked. The regime is clearly testing out the tactics it used in 2020. For the first time, however, Lukashenka has admitted that the 2020 shutdown was ordered by the regime, not caused by some foreign intervention.

I vividly remember the days of the 2020 election and the beginning of the protests. I was fortunate to be involved in the epicentre of the activities. At the time, I was a culture journalist in Minsk, far from politics or civil activism but not far enough to miss what was happening. When a team of British journalists and documentary filmmakers needed a fixer on the ground ahead of the election, I gladly agreed to help.

It was just days before the election, and many foreign journalists still hadn’t received accreditation from Lukashenka’s Foreign Ministry. A classic dictatorial trick: don’t openly forbid anything, just don’t allow it.

It’s hard to explain how one becomes so desensitised to human rights abuses. The political and civil awakening of Belarusians didn’t happen overnight. We were tired. Tired of the regime’s response to the pandemic, denying Covid-19 and leaving us to fend for ourselves. Tired of seeing Lukashenka’s challengers like Siarhei Tsikhanouski and Viktar Babaryka being detained before they could officially run against the dictator. Tired of watching solidarity chains being brutally dispersed by police. Tired of decades of fake elections.

So, we were prepared. Telegram was boiling with new chats, organisational channels and news coverage – our safe space where thousands of Belarusians tracked real information and self-organised, following protest tips and updates. We were all equipped with VPN apps for security and for reading independent Belarusian media sites, which had been blocked in the country. We gathered our physical protest in dispersed groups, making it harder to track and suppress. But still, we couldn’t anticipate every dictatorial trick up the regime’s sleeve, and the scale of resistance was unprecedented.

On the morning of 9 August 2020, the main election day, mobile providers announced technical issues “due to circumstances beyond our control”. As there was a state-owned monopoly on the internet, private companies had no choice but to comply with the government’s non-public orders to restrict access to the internet.

But the election day plan for Belarusians aspiring for change was clear: go to your polling station, vote for opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, take a picture of your ballot for independent online counting, and if possible, wait outside the polling station for the local commission to count the result.

That evening, many independent Belarusian and foreign journalists gathered at Tsikhanouskaya’s team headquarters. Maria Kalesnikava was also there as another leader of the united team and representative of jailed Viktar Babaryka, and Maksim Znak, as their lawyer. Many representatives of civic initiatives were also at the headquarters. It felt like a community of white knights, leading us to a bright future.

I remember seeing a Radio Svaboda (the Belarusian service from Radio Free Europe) journalist there wearing a press vest with a helmet attached to his belt. For a moment, I thought it was a bicycle helmet, assuming he’d cycled there since central stations on the Minsk metro were closed to prevent gatherings. Then it hit me: it was a protective helmet. That’s when the gravity of our situation truly sank in.

As the evening progressed, the atmosphere grew tense. Tsikhanouskaya’s team collected independent data from polling stations, showing overwhelming support for her and the change she represented. Outside, crowds carrying white-red-white national flags (which were abolished in 1995 in favour of a Soviet-era style flag) marched toward the Minsk Hero City Obelisk. Despite the internet blackout, people had organised and followed earlier calls from Telegram channels to gather in specific parts of Minsk, determined to peacefully defend their votes, voices and rights. Most journalists rushed to cover the growing protests.

Within just a few hours, euphoria gave way to a harsh reality: Lukashenka would never willingly relinquish power.

That night, I heard stun grenades for the first time. As I waited in the centre for my journalist group, who had plunged into the crowds, the ground shook with every explosion at the Obelisk and other parts of Minsk. I lost count of the grenades launched. Without internet access, nobody fully knew what was happening across the city.

For hours, I stayed up, calling friends around the city and country, piecing together information, and relaying updates via SMS to friends living in Lithuania who could see news online and were worried sick about us.

This pattern repeated for three nights. Peaceful protests. Police attacks. Internet blackouts. No decent reaction from the regime apart from the predictable announcement on Monday 10 August: Lukashenka had “won” with 80% of the votes. How surprising.

The most harrowing part was the morning after each night of violence. As the internet partially flickered back on for a short time, Belarusians flooded independent media and Telegram channels with photos and videos they had captured. We saw tens of thousands protesting across Belarus, standing unarmed against fully-equipped riot police. Stun grenades and rubber bullets caused open wounds. Men and women were savagely beaten. Detainees were tortured in police stations, prison trucks and the notorious Okrestina Street Detention Facility. Our cameraman returned with a wound in his collarbone from a stun grenade fragment.

Then came the first fatality from police violence: Aliaksandr Taraikouski. Investigations have found that he was shot in the chest, and the world was horrified alongside us, seeing the footage captured by an Associated Press correspondent. But when the tragedy first came to light, the government tried to claim that he died when an explosive device detonated in his hand, which they said he planned to throw at police. There is no evidence of this.

It was terrifying. It still looks terrifying as I re-watch footage from the protests or documentaries about the events of 2020 in Belarus.

We knew one thing for certain – we couldn’t move forward with Lukashenka. We still can’t. We continue to fight for our rights and freedoms, navigating countless violations by the dictator and his regime. Sometimes, it feels impossible to imagine what achieving our goals might feel like in practice. But as generations of Belarusians have paid a high price for the future, we cannot pass this burden to the next. It is our responsibility, and we rely on democratic countries to stand with us on this path.

There is too much at stake in the world right now, especially in our region. Having one less dictatorship is a victory for all of us.

The start of Donald Trump’s second term of office as US president was marked with a flurry of executive orders – directives given by the president directly to the federal government without the need for approval by Congress.

Ever since George Washington, US presidents have had the power to issue such orders as stated within Article 2 of the Constitution (“the executive power shall be vested in a president”). This article justifies presidents' interventions, and allows them to enact their own policy vision or agenda.

Washington issued eight. Of the more than 14,000 executive orders issued since, Franklin D Roosevelt has been their biggest user, issuing 3,721 during his more than 12 years in office. Joe Biden issued 162 orders during his time in office.

While in principle they seem to allow the president to change the law on a whim, executive orders are subject to judicial review and can be overturned if they conflict with the law or the constitution. Indeed, many believe that Trump’s new orders could be “tied up in courts or legislatures for years”.

As an example, the American Civil Liberties Union has announced it is challenging a new order that seeks to end birthright citizenship of all children born in the United States regardless of race, colour, or ancestry.

The flurry of new orders marks a turnaround for Trump. In March 2016, he criticised Barack Obama for their use:

“Executive orders sort of came about more recently. Nobody ever heard of an executive order, then all of a sudden Obama — because he couldn’t get anybody to agree with him — he starts signing them like they’re butter, so I want to do away with executive orders for the most part.”

Trump’s enthusiasm for new executive orders, plus the revocation of many of those issued by his predecessor, have implications for freedom of expression.

Revocation of Biden executive orders

One of Trump’s first tasks was to revoke 78 of President Biden’s orders and Presidential Memoranda, including several measures supporting diversity and tackling discrimination.

Explaining this decision, President Trump wrote: “The previous administration has embedded deeply unpopular, inflationary, illegal, and radical practices within every agency and office of the Federal Government.

“The injection of ‘diversity, equity, and inclusion’ into our institutions has corrupted them by replacing hard work, merit, and equality with a divisive and dangerous preferential hierarchy. Orders to open the borders have endangered the American people and dissolved Federal, State, and local resources that should be used to benefit the American people. Climate extremism has exploded inflation and overburdened businesses with regulation.”

The orders that Trump has proposed to revoke include those which: prevent discrimination towards transgender and gay people; support educational opportunities for people from ethnic minority backgrounds; promote access to cultural and learning services, such as libraries; and encourage regulation around the use of AI (artificial intelligence).

New executive orders

Trump has introduced a raft of new executive orders.

Free speech

For Index, one of Trump’s most eye-catching orders is one for “restoring freedom of speech and ending federal censorship”.

President Trump acknowledges "the right of the American people to speak freely in the public square without government interference", as enshrined in the First Amendment to the US Constitution. He then says that “the previous administration trampled free speech rights by censoring Americans’ speech on online platforms, often by exerting substantial coercive pressure on third parties, such as social media companies, to moderate, deplatform, or otherwise suppress speech that the federal government did not approve”.

He adds: “Under the guise of combating ‘misinformation’ ‘disinformation’ and ‘malinformation’ the federal government infringed on the constitutionally protected speech rights of American citizens across the United States in a manner that advanced the government’s preferred narrative about significant matters of public debate. Government censorship of speech is intolerable in a free society."

The order requires the US Attorney to investigate the government's activities over the past four years to decide whether any remedial actions need to be taken.

Trump fails to address some of the nuances when it comes to online content moderation. We outlined these when we responded to the changes at Meta earlier this month. Whilst we have reservations about moderation, we also have reservations about a complete lack of moderation. An unfiltered world of lies and hate speech can, and does, impact many people's freedom of expression. A delicate balance must be sought but the new president doesn't appear interested in striking this balance.

His move to “protect” free speech has also drawn much criticism and allegations of hypocrisy, given his penchant for threatening and suing journalists and political opponents. He famously referred to journalists as the “enemy of the people” and has sued five media companies, with some lawsuits still ongoing. His lawsuit against former political opponent Hillary Clinton was also dismissed as "frivolous, both factually and legally" by a federal judge, and Trump and his attorney were ordered to pay nearly $1 million in penalties.

Gender identity

As well as revoking a number of Biden-era orders, President Trump has made a new order aimed at “defending women from gender ideology extremism and restoring biological truth”.

In the order, he says: “Efforts to eradicate the biological reality of sex fundamentally attack women by depriving them of their dignity, safety, and wellbeing. The erasure of sex in language and policy has a corrosive impact not just on women but on the validity of the entire American system.”

At Index, we have charted how discussions around gender have become toxic and how voices on both sides have been silenced. But once again Trump fails to acknowledge any nuance here and his own personal prejudices come out. This is not about allowing a plurality of voices and opinions – it is about prioritising one voice over another.

The order has drawn serious concerns for the free expression of transgender people, as it attempts to erase non-binary and transgender identities. For example, the order directs that passports, visas and other government documents must reflect male and female as the only two sexes, and government agencies will be banned from promoting gender transition. “As of today, it will henceforth be the official policy of the United States government that there are only two genders, male and female,” said Trump during his inaugural speech on Monday.

Stopping diversity, equity and inclusion

In an order titled Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs and Preferencing, Trump vowed to halt diversity, equity and inclusion programmes within the federal government, which he described as generating “immense public waste and shameful discrimination”.

This is an incredibly knotty issue. Susie Linfield, professor of journalism at New York University, raised her concerns about DEI programmes in this thoughtful piece for Index when she talked about a culture of coercion that has been created on US campuses.

But to end these programmes rather than improve them could see fewer opportunities for, and the further discrimination and silencing of, ethnic minority voices and people of colour in government bodies and agencies. The private sector also appears to be following suit. According to Forbes, several high-profile companies appear to be either ending or altering their US DEI programmes, including Amazon, Meta and McDonald’s.

Pardons for 6 January rioters

As expected, President Trump has pardoned or commuted the sentences of all those involved in the US Capitol riots of 6 January 2021, saying it puts an end to “a grave national injustice”. The move involves more than 1,500 people, including 14 members of the far-right groups the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers. More than 600 were charged with assaulting, resisting or obstructing law enforcement, using a deadly or dangerous weapon or causing serious bodily injury to a police officer.

Such an order muddies the waters legally of what constitutes “peaceful protest”, confusing the right to object to political decisions with the right to be violent. It also potentially emboldens those looking to enact the latter. It's also worth noting that this violence was a response to an election that was won fairly. What could happen in four years time if people decide they don't like the election outcome?

U-turns on social media bans

Having previously backed a TikTok ban during his first term in office, Trump has since changed his position on this.

Last year, a law was passed in Congress under Biden, which required the Chinese technology company that owns TikTok – Bytedance – to either find a US buyer for the US version of the app, or face a complete ban in the USA. The law gave ByteDance until 19 January 2025 to sell in order to avoid a ban. But Trump has just signed an executive order which suspends the sale or ban by granting the company a 75-day extension.

National security concerns have been cited for the need to ban the platform, by both Biden's and Trump’s former governments, including that the Chinese government could use TikTok for potential spying or data collection on American citizens. But there seems to be little-to-no evidence that supports these concerns. This is not to say that it isn't happening, but that currently the threshold for a ban has not been met. The ban therefore posed concerns for free speech and access to information, given that more than 170 million Americans use TikTok, many of whom (particularly younger people) use it for news.

However, this u-turn seems less about Trump being a guardian of free expression, and more about pursuing his own marketing agenda. The president has gained huge popularity on the platform, with 15 million followers, and some of his videos have amassed more than 60 million views. He used it extensively during last year’s presidential campaign.

Risks to impartial information and journalism

On top of Trump’s disparaging remarks made about journalists, several executive orders have been signed which are cause for concern for citizens’ access to impartial and truthful information. This includes the creation of a Department of Government Efficiency, which will be headed up by X owner Elon Musk. The new advisory body will aim to cut government spending.

With Musk at its helm, critics are concerned about the implications for a free press, given the tech giant’s attitudes towards the media, having previously called for the defunding of American public broadcasters such as NPR. Policy decisions taken at X also indicate that Musk would not be a purveyor of a free press – a recent change to the social media platform’s blocking policy means that accounts can now view who has blocked them, which is expected to increase the rate of harassment towards journalists, particularly women and people of colour.

The president’s attitude towards the spread of false information online also indicates that it may become harder for Americans to discern between truth and falsehood. Trump has previously referred to efforts to tackle political mis- and disinformation as “the censorship cartel”, and several new executive orders imply a worrying approach to authoritative, and expert-led, global perspectives on issues such as climate change and pandemics. This includes an order withdrawing the US from the World Health Organization, and another withdrawing it from the Paris Climate Agreement, showing even more movement away from the general consensus on public health and climate crises.