Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

The undersigned organisations condemn the harassment of artist, political cartoonist and activist Badiucao, which has taken place via email, in the media, and on social media in the last week. The harassment began as Badiucao was preparing to publish a statement criticising the human rights situation in Hong Kong. The statement was providing context to his artwork – a short video – that was being exhibited in the city. Like much of Badiucao’s work, the video sought to champion the right to freedom of expression and challenge authoritarianism.

Badiucao was one of more than a dozen artists featured in the three-minute video compilation put together by the Milan-based digital gallery, Art Innovation, on billboards during the Art Basel fair in Hong Kong last week. The 4-second clip, entitled “Here and Now”, showed Badiucao silently mouthing the words “you must take part in revolution” – the title of his newly-published graphic novel and a Mao Zedong quote. It was broadcast hourly between 28 March and 2 April.

On 1 April, Badiucao contacted several media organisations to let them know he would be publishing a statement about the artwork later that evening. Some of them then contacted Art Innovation for comment. Shortly thereafter, Badiucao received an email from the gallery warning him not to publish his statement. They told him that legal action would “definitely” follow if content “against the Chinese government is published”. The gallery later responded to media requests saying that the exhibition “had nothing to do with political messages”.

Badiucao went on to publish his statement. In it, he said: “This art action underscores the absurdity of Hong Kong’s current civil liberties and legal environment. And it would remind everyone that art is dead when it offers no meaning.” The exhibition was removed from the billboards the following morning, despite having been scheduled to be displayed until 3 April.

In a second email to Badiucao, Art Innovation said that his actions had already resulted in financial implications, as well as legal actions, “which will be directed against you”. They demanded that he immediately remove all posts from his personal social media accounts related to the exhibition and claimed that failure to comply could “result in further legal consequences”. They said their lawyers were already working to “initiate appropriate legal action” against him.

On 3 April, Art Innovation publicly accused Badiucao of having provided them with false information and of having violated the contract he signed by submitting political content. “[W]e can consider it a crime,” they wrote on social media. Badiucao said he had submitted the artwork under the pseudonym Andy Chou because the video clip was to be shown in Hong Kong, where the authorities had previously shut down his exhibition. He said he never concealed his identity from the gallery and that they knew that he was behind the artwork.

Art Innovation would also have been aware of the distinctly political nature of Badiucao’s artwork given that they first contacted him via social media, where he regularly shares his artwork with his more than 100k followers, in 2022. They invited him to collaborate on a billboard exhibition during Art Basel in Miami that year, to which he contributed a satirical image of Chinese president Xi Jinping.

“We are appalled at the behaviour of this Italian gallery, which claims to ‘love everything that is outside the rules’ and ‘love the freedom of artists’ and yet harasses and tries to silence an artist that stands for exactly those principles,” the undersigned organisations said. “Badiucao must be applauded for his efforts to creatively challenge censorship and authoritarianism in such a repressive regime. Art Innovation should immediately withdraw their legal threats, issue a public apology to Badiucao, and refrain from further harassment of the artist.”

Signed:

Index on Censorship

Alliance for Citizens Rights

Art for Human Rights

ARTICLE 19

Australian Cartoonists Association

Australia Hong Kong Link

Befria Hongkong

Blueprint for Free speech

Civil Liberties Union for Europe

Cartooning for Peace

Cartoonists Rights Network International

The Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong Foundation

DOX Centre for Contemporary Art

European Federation of Journalists

Foundation Atelier for Community Transformation ACT

Freemuse

Freedom Cartoonists

Freiheit für Hongkong

Hong Kong Committee in Norway

Hong Kong Forum, Los Angeles

Hong Kong Watch (HKW)

Hongkongers in Britain (HKB)

Hong Kongers in San Diego

Hong Kongers in San Francisco Bay Area

Human Rights in China (HRIC)

Human Rights Foundation (HRF)

Humanitarian China

IFEX

Lady Liberty Hong Kong

NGO DEI

NY4HK

Osservatorio Balcani Caucaso Transeuropa (OBCT)

Croatian Journalists’ Association (HND)

Trade Union of Croatian Journalists

PEN America

PEN International

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

Richardson Institute – Lancaster University

The Rights Practice

Safeguard Defenders

StraLi for Strategic Litigation

Stand with Hong Kong EU

Toronto Association for Democracy in China 多倫多支聯會

Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP)

Washingtonians Supporting Hong Kong (DC4HK)

Notes:

In the age of online information, it can feel harder than ever to stay informed. As we get bombarded with news from all angles, important stories can easily pass us by. To help you cut through the noise, every Friday Index will publish a weekly news roundup of some of the key stories covering censorship and free expression from the past seven days. This week, we look at targeted families of activists in two parts of the world and how the US president is punishing those who defy him.

Activists under pressure: Human rights defenders in Balochistan face new threats

On 5 April, the father of Baloch human rights defender Sabiha Baloch was arrested by Pakistani authorities, and his whereabouts are currently unknown. This has been widely considered as an attempt to silence Sabiha Baloch, who advocates for the rights of Baloch people, in particular against the killings, enforced disappearances and arbitrary arrests that have been happening for years.

There are reports that authorities refuse to release Baloch’s father until she surrenders herself, and raids are being carried out in an attempt to arrest her. This is not the first attempt to silence her. Other family members have previously been abducted and held in detention for several months.

Two days later on 7 April, another Baloch human rights defender, Gulzadi Baloch, was arrested. It is believed that her arrest was particularly violent, and that she was beaten and dragged out onto the street. Both women are members of the Baloch Yakjehti Committee, which advocates for human rights for Baloch people. Its founder, Mahrang Baloch, was arrested on 22 March along with 17 other protesters, after they staged a sit-in to demand the release of members of their group. During the crackdown, at least three protesters were reportedly killed.

Toeing the line: Trump gets to work silencing critics

US President Donald Trump has made several attempts to silence or punish his critics this week. On 9 April, he signed an executive order placing restrictions on the law firm Susman Godfrey, including limiting attorneys from accessing government buildings and revoking security clearances. The firm represented Dominion Voting System in their defamation lawsuit against Fox, accusing the media company of lying about a plot to steal the election and claiming Dominion was involved. It ended with Dominion getting a $797.5m settlement in April 2023. This week’s move comes after Trump took similar measures to target five more law firms, connected with his political rivals.

The next day, Trump took aim at former homeland security officials, Miles Taylor and Chris Krebs, who both served in Trump’s first administration and both publicly spoke out against Trump’s election fraud narrative.

Taylor turned whistleblower in 2018, anonymously speaking out in a New York Times article and after quitting writing a book, before eventually revealing his identity. Trump has accused him of leaking classified information. Krebs, whose job it was to prevent foreign interference in elections, corrected rumours about voter fraud in the 2020 election, and was subsequently fired by Trump. Trump has ordered the Department of Justice to investigate the two men, and revoke their security clearances.

Attorney and former congresswoman Liz Cheney described the move as “Stalinesque”. As he signed the executive orders, Trump took the opportunity to repeat lies about a stolen election.

Not safe to report: Journalists killed as Israeli airstrike hits media tent

On Monday, an Israeli airstrike hit a tent in southern Gaza used by media workers, killing several journalists and injuring others. The journalists killed were Hilma al-Faqawi and Ahmed Mansour, who worked for Palestine Today, wth Mansour dying later following severe burns. Yousef al-Khozindar, who was working with NBC to provide support in Gaza, was also killed.

Reuters say they have verified one video, which shows people trying to douse the flames of the tent in the Nasser Hospital compound. The Committee to Protect Journalists and the National Union of Journalists have denounced Israel’s strike on the journalists’ tent.

The Israel Defense Forces wrote on X: “The IDF and ISA struck the Hamas terrorist Hassan Abdel Fattah Mohammed Aslih in the Khan Yunis area overnight” … “Asilh [sic], who operates under the guise of a journalist and owns a press company, is a terrorist operative in Hamas’ Khan Yunis Brigade.”

The deaths add to the growing number of journalists and media workers who have been killed in the conflict since 7 October 2023, which the International Federation of Journalists place at over 170. The journalists killed are Lebanese, Syrian, Israeli and overwhelmingly Palestinian. Journalists are protected under International Humanitarian law. This is vital not only for the safety of individuals, but so that accurate information can be broadcast locally and internationally.

Whistleblowing triumphs: Apple settles unfair labour charges

Whistleblower Ashley Gjøvik came out on top on 10 April, when Apple agreed to settle labour rights charges after she claimed their practices were illegal, including barring staff from discussing working hours, conditions and wages, and speaking to the press.

Gjøvik was a senior engineering programme manager at the tech giant, when she raised her concerns about toxic waste under her office. She was fired after engaging in activities that should be protected under labour rights laws. She was let go after supposedly violating the staff confidentiality agreement.

In a memorandum, Gjøvik highlighted that there is still plenty to be concerned about. She wrote: “The settlement’s policy revisions, while significant—do not address several categories of retaliation and coercive behavior that remain unremedied or unexamined, including: surveillance, email interception, and device monitoring in relation to protected activities; threats or internal referrals aimed at chilling protected disclosures; and retaliation based on public statements regarding working conditions.”

Circles of influence: Hong Kong family taken in for questioning

On Thursday, the Hong Kong national security police targeted the family of Frances Hui, a staff member at the Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong (CFHK) Foundation, and a US resident.

Hui’s parents were taken in for questioning, even though Hui cut ties with them when she left for the USA in 2020. She now fights for democracy and freedom in Hong Kong, from abroad. This week’s move comes shortly after the USA placed sanctions on six Chinese and Hong Kong officials who have enforced repressive national security policies in Hong Kong.

In December 2023, Hong Kong police put out an arrest warrant for Hui, and placed a HK$1 million bounty on her head.

The CFHK Foundation said: “By placing a bounty on her and other U.S-based Hong Kong activists, the Hong Kong authorities are encouraging people to kidnap them on U.S. soil in return for a reward.”

Modern medicine is a wonderful thing. Before Edward Jenner’s development of the smallpox vaccination in 1796, infectious diseases and viruses killed millions. The introduction of anaesthetic gases during surgical procedures in 1846 eliminated the excruciating pain of surgery. And before Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin in 1928, people died unnecessarily from cuts and grazes.

But the benefits of modern medicine are not felt equally around the world. In this issue, we explore the forgotten patients in global healthcare settings – the marginalised groups who fall through the cracks or are actively shut out of healthcare provision, then ignored or silenced when they raise concerns.

Just like free speech, healthcare is an indisputable human right. But for many around the globe, both these rights are being removed in conjunction with each other. Through telling their stories, this edition aims to shine a light on these injustices and – we hope – empower more people to speak up for the right to health for themselves and others.

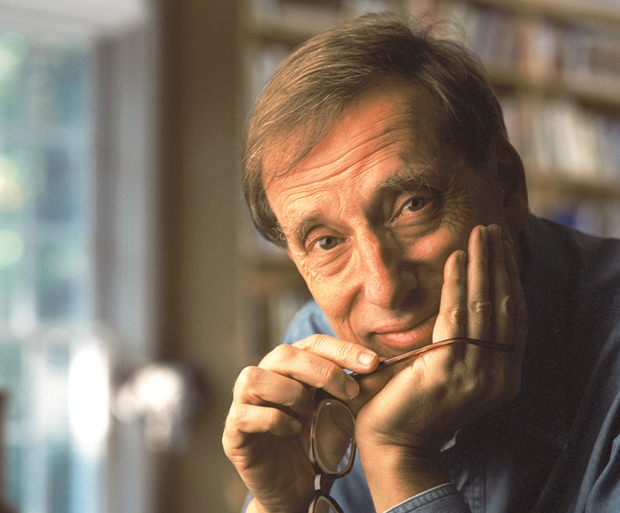

Ariel Dorfman is an Argentine-Chilean-American novelist, playwright, and human rights activist. He served as a cultural adviser to President Salvador Allende until the coup by General Augusto Pinochet in 1973

Michael Rosen is one of Britain’s most beloved writers and performance poets. He has written over 200 books, including The Sad Book, a meditation on bereavement after the death of his son Eddie, Many Different Kinds of Love, a story of life, death and the NHS and Getting Better – life lessons on going under, getting over it, and getting through it, an examination of loss and mourning and what comes next.

Yassmin Abdel-Magied is a Sudanese-Australian writer, journalist and broadcaster

Modern medicine is a wonderful thing. Before Edward Jenner’s development of the smallpox vaccination in 1796, infectious diseases and viruses killed millions. The introduction of anaesthetic gases during surgical procedures in 1846 eliminated the excruciating pain of surgery. And before Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin in 1928, people died unnecessarily from cuts and grazes.

But the benefits of modern medicine are not felt equally around the world. In this issue, we explore the forgotten patients in global healthcare settings – the marginalised groups who fall through the cracks or are actively shut out of healthcare provision, then ignored or silenced when they raise concerns.

Just like free speech, healthcare is an indisputable human right. But for many around the globe, both these rights are being removed in conjunction with each other. Through telling their stories, this edition aims to shine a light on these injustices and – we hope – empower more people to speak up for the right to health for themselves and others.

A bitter pill to swallow: Sarah Dawood

Not all healthcare is made equal, and pointing this out can have serious consequences

The Index: Mark Stimpson

From elections in Romania to breaking encryption in the UK: a tour of the world’s most pressing free expression issues

Rape, reputation and little recourse: Samridhi Kapoor, Hanan Zaffar

Indian universities have a sexual violence problem that no one is talking about

Georgian nightmare: Ruth Green

Russian-style laws are shutting down more conversations in Georgia, with academia feeling the heat

Botswana’s new era: Clemence Manyukwe

From brave lawyer to president – could the country’s new leader put human rights front and centre?

Venezuela’s prison problem: Catherine Ellis

The disputed new president has a way of dealing with critics – locking them up

Forbidden words: Salil Tripathi

The Satanic Verses is back in India’s bookshops. Or is it?

The art of resistance: Alessandra Bajec

A film, a graffiti archive and a stage play: three works changing the narrative in Tunisia

A tragic renaissance: Emily Couch

The pen is getting mightier and mightier in Ukraine

In the red zone: Alexandra Domenech

Conscription is just one of the fears of an LGBTQ+ visual artist in Russia

Demokratia dismantled: Georgios Samaras

The legacy of the Predator spyware scandal has left a dark stain on Greece

Elon musk’s year on X: Mark Stimpson

The biggest mystery about Musk: when does he sleep?

Keyboard warriors: Laura O’Connor

A band of women are fighting oppression in Myanmar through digital activism

Behind the bars of Saydnaya prison: Laura Silvia Battaglia

Unspeakable horrors unfolded at Syria’s most notorious prison, and now its survivors tell their stories

Painting a truer picture: Natalie Skowlund

Street art in one Colombian city has been sanitised beyond recognition

The reporting black hole: Fasil Aregay

Ethiopian journalists are allowed to report on new street lights, and little else

Whistleblowing in an empty room: Martin Bright

Failures in England’s maternity services are shrouded in secrecy

An epidemic of corruption: Danson Kahyana

The Ugandan healthcare system is on its knees, but what does that matter to the rich and powerful?

Left speechless: Sarah Dawood

The horrors of war are leaving children in Gaza unable to speak

Speaking up to end the cut: Hinda Abdi Mohamoud

In Somalia, fighting against female genital mutilation comes at a high price

Doctors under attack: Kaya Genç

Turkey’s president is politicising healthcare, and medics are in the crosshairs

Denial of healthcare is censoring political prisoners – often permanently: Rishabh Jain, Alexandra Domenech, Danson Kahyana

Another page in the authoritarian playbook: deny medical treatment to jailed dissidents

The silent killer: Mackenzie Argent

A hurdle for many people using the UK’s National Health Service: institutional racism

Czechoslovakia’s haunting legacy: Katie Dancey-Downs

Roma women went into hospitals to give birth, and came out infertile

An inconvenient truth: Ella Pawlik

While Covid vaccines saved millions of lives, those with adverse reactions have been ignored

Punished for raising standards: Esther Adepetun

From misuse of money to misdirecting medicines, Nigerian healthcare is rife with corruption

Nowhere to turn: Zahra Joya

Life as they know it has been destroyed for women in Afghanistan, and healthcare provision is no different

Emergency in the children’s ward: Shaylim Castro Valderrama

The last thing parents of sick children expect is threats from militia

We need to talk about Sudan: Yassmin Abdel-Magied

Would “a battle of narratives” give the war more attention?

RFK Jr could be a disaster for American healthcare: Mark Honigsbaum

An anti-vaxxer has got US lives in his hands

The diamond age of death threats: Jemimah Steinfeld

When violent behaviour becomes business as usual

Free speech v the right to a fair trial: Gill Phillips

Are contempt of court laws fit for the digital age?

An unjust trial: Ariel Dorfman

A new short story imagines a kangaroo court of nightmares, where victims become defendants

Remember the past to save the future: Sarah Dawood, Diane Fahey

Published exclusively, the issues of antisemitism and colonialism are recorded through poetry

Where it’s more dangerous to carry a camera than a gun: Antonia Langford

A singer meets filmmakers in Yemen, and both take risks to tell her story

The fight for change isn’t straightforward: Shani Dhanda

The Last Word, on exclusion and intersectional discrimination