Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The newsroom at DR. (Credit: James Cridland / Flickr)

Known across Europe for its journalistic quality and as an exporter of hit political dramas, Danish state broadcaster DR will this autumn be forced to make unprecedented layoffs in what some are calling an act of “revenge” by the government.

In a package of media reforms agreed by Denmark’s governing right-wing coalition, DR is to have its funding cut by 20% and will be forced to let several hundred staff go as a result.

A significant driver of the cuts is the right-wing populist Danish People’s Party (DF), a political movement founded in the mid-1990s that has grown to become a supporting partner of the conservative coalition government. DF politicians have been known to discredit public media outlets and encouraged voters towards alternative websites pushing strongly nationalistic content, with DR often caricatured as a hotbed of left wingers and politically correct liberals.

One longtime editor from DR’s current affairs team, who wished to remain anonymous, said he believes the cuts are a clear political power play: “This thing about DR being left wing goes 50 years back to the days when DR was a monopoly in Denmark when it was accused of being biased, but the funny thing is that all the DR stars that went into politics over many years all have gone to right-wing parties. In the past, there have been examples of DR leaning a little to the left, but nothing on the scale of what they’re being accused off; it simply makes no sense.”

Thoughts have now turned to where exactly the cuts will bite, combined with anger among DR journalists at what they see as a personal attack.

“This will cost around 600-700 jobs and people will get the sack in October,” says the editor. “Are they pissed off? Of course they are, because they feel it’s unjust. The budget of DR is £450 million a year and employs about 3,000 people. Yes, there’s room for cuts, they just have to be based on facts and necessities and not the whims of vengeful politicians.”

Traditionally DR has used large-scale audience capture to divert viewers and listeners towards its more educational and politically analytical content. Journalists fear that by being forced to hand over more popular content to commercial and entertainment-only channels, it will end up shedding audience share, which will then be used as a political justification for further cuts in public spending. The government has also removed the public broadcaster’s first refusal on international sporting events which bring in large numbers of viewers, much to the delight of commercial broadcasters.

DR’s politically cautious general director, Maria Rørbye Rønn, has said that the cutbacks will have serious consequences for the organisation’s users, viewers and listeners. Unions have been more forthright, with DR’s most senior union representative, Henrik Friis Vilmar, telling colleagues in an open letter: “[T]he ambitions of the Danish media are to my mind especially important at a time where Danish-produced critical news is more important than ever in order to stem the tide of fake news and troll factories.” Friis Vilmar went on to warn that the ability of DR to critically observe Danish society was at serious risk.

Morten Østergaard, a member of parliament for the opposition Danish Social Liberal Party, has described the cuts as a “vendetta against DR”, while the Social Democrats have also refused to back the government deal, claiming that cuts will mean less Danish content and less coverage of life in Denmark, which would also negatively impact the Danish democratic system.

The government has responded that it is saving Danes money by effectively giving them a small tax break, though the difference this will make to people’s personal finances is negligible, with people saving at most around 160 euros a year. As part of the package of reforms the government is abolishing the current system of media licences and instead financing DR through the tax system.

DR was founded in 1925 and has a reputation for being one of Europe’s most developed and innovative public broadcasters. In 2007 it moved to a new high-tech media campus on the south side of Copenhagen and currently runs six different TV channels and eight radio channels, including a comprehensive local radio network.

The opposition parties in the Danish parliament have said that they will restore DR’s funding if they win the next election. This might be welcome news for public service journalists, but with the axe hanging over so many of its staff, the next round of elections will see a leaner public broadcaster painfully aware that its detractors in power are watching its every move.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Incidents reported to Mapping Media Freedom since 24 May 2014.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:14|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_raw_html]JTNDaWZyYW1lJTIwd2lkdGglM0QlMjI3MDAlMjIlMjBoZWlnaHQlM0QlMjIzMTUlMjIlMjBzcmMlM0QlMjJodHRwcyUzQSUyRiUyRm1hcHBpbmdtZWRpYWZyZWVkb20udXNoYWhpZGkuaW8lMkZzYXZlZHNlYXJjaGVzJTJGNzklMkZtYXAlMjIlMjBmcmFtZWJvcmRlciUzRCUyMjAlMjIlMjBhbGxvd2Z1bGxzY3JlZW4lM0UlM0MlMkZpZnJhbWUlM0U=[/vc_raw_html][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1532621766097-fa067966-c17c-8″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]We the undersigned respectfully urge the Danish Parliament to vote in favour of bill L 170 repealing the blasphemy ban in section 140 of the Danish criminal code, punishing “Any person who, in public, ridicules or insults the dogmas or worship of any lawfully existing religious community”.

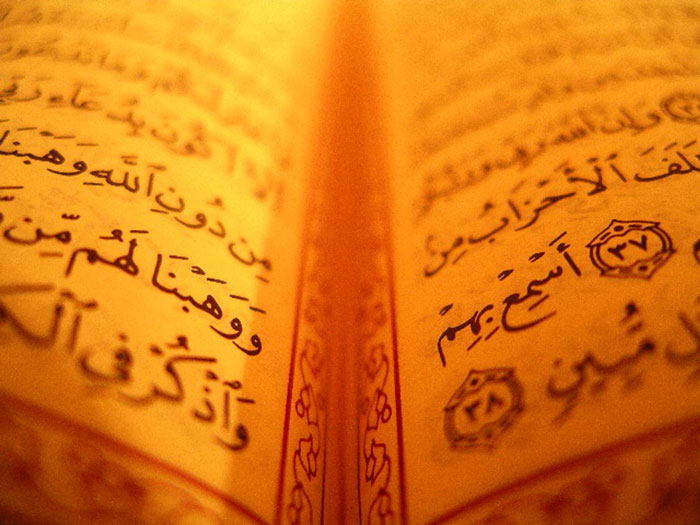

Denmark is recognised as a global leader when it comes to the protection of human rights and freedom of expression. However, Denmark’s blasphemy ban is manifestly inconsistent with the Danish tradition for frank and open debate and puts Denmark in the same category as illiberal states where blasphemy laws are being used to silence dissent and persecute minorities. The recent decision to charge a man – who had burned the Quran – for violating section 140 for the first time since 1971, demonstrates that the blasphemy ban is not merely of symbolic value. It represents a significant retrograde step in the protection of freedom of expression in Denmark.

The Danish blasphemy ban is incompatible with both freedom of expression and equality before the law. There is no compelling reason why the feelings of religious believers should receive special protection against offence. In a vibrant and pluralistic democracy, all issues must be open to even harsh and scathing debate, criticism and satire. While the burning of holy books may be grossly offensive to religious believers it is nonetheless a peaceful form of symbolic expression that must be protected by free speech.

Numerous Danes have offended the religious feelings of both Christians and Muslims without being charged under section 140. This includes a film detailing the supposed erotic life of Jesus Christ, the burning of the Bible on national TV and the publication of cartoons depicting the prophet Muhammed. The Cartoon affair landed Denmark in a storm of controversy and years of ongoing terrorist threats against journalists, editors and cartoonists. When terror struck in February 2015 the venue was a public debate on blasphemy and free speech.

In this environment, Denmark must maintain that in a liberal democracy, laws protect those who offend from threats, not those who threaten from being offended.

Retaining the blasphemy ban is also incompatible with Denmark’s human rights obligations. In April 2017 Council of Europe Secretary General Thorbjørn Jagtland emphasised that “blasphemy should not be deemed a criminal offence as the freedom of conscience forms part of freedom of expression”. This position is shared by the UN’s Human Rights Committee and the EU Guidelines on freedom of expression and religion.

Since 2014, The Netherlands, Norway, Iceland and Malta have all abolished blasphemy bans. By going against this trend Denmark will undermine the crucial European and international efforts to repeal blasphemy bans globally.

This has real consequences for human beings, religious and secular, around the globe. In countries like Pakistan, Mauretania, Iran, Indonesia and Russia blasphemy bans are being used against minorities as well as political and religious dissenters. Denmark’s blasphemy ban can be used to legitimise such laws. In 2016 the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief pointed out that “During a conference held in Jeddah (Saudi Arabia) [in 2015], the Danish blasphemy provision was cited by one presenter as an example allegedly indicating an emerging international customary law on “combating defamation of religions”.

Blasphemy laws often serve to legitimise violence and terror. In Pakistan, Nigeria and Bangladesh free-thinkers, political activists, members of religious minorities and atheists have been killed by extremists. In a world where freedom of expression is in retreat and extremism on the rise, democracies like Denmark must forcefully demonstrate that inclusive, pluralistic and tolerant societies are built on the right to think, believe and speak freely. By voting to repeal the blasphemy ban Denmark will send a clear signal that it stands in solidarity with the victims and not the enforcers of blasphemy laws.

Jacob Mchangama, Executive director, Justitia

Steven Pinker, Professor Harvard University

Ahmedur Rashid Chowdhury, Exiled editor of Shuddhashar, 2016 winner International Writer of Courage Award

Pascal Bruckner, Author

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Human Rights Activist Founder of AHA Foundation,

Dr. Elham Manea, academic and human rights advocate (Switzerland)

Sultana Kamal, Chairperson, Centre for Social Activism Bangladesh

Deeyah Khan, CEO @Fuuse & founder @sister_hood_mag.

Fatou Sow, Women Living Under Muslim Laws

Elisabeth Dabinter, Author

William Nygaard, Publisher

Flemming Rose, Author and journalist

Jodie Ginsberg, CEO, Index on Censorship

Kenan Malik, Author of From Fatwa to Jihad

Thomas Hughes, Executive Director Article 19

Suzanne Nossel, executive director of PEN America

Pragna Patel – Director of Southall Black Sisters

Leena Krohn, Finnish writer

Jeanne Favret-Saada, Honorary Professor of Anthropology, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes,

Maryam Namazie, Spokesperson, Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain

Fariborz Pooya, Host of Bread and Roses TV

Frederik Stjernfelt, Professor, University of Aalborg in Copenhagen

Marieme Helie Lucas, Secularism Is A Women’s Issue

Michael De Dora, Director of Government Affairs, Center for Inquiry

Robyn Blumner, President & CEO, Center for Inquiry

Nina Sankari, Kazimierz Lyszczynski Foundation (Poland).

Sonja Biserko, Founder and president of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia

James Lindsay, Author

Malhar Mali, Publisher and editor, Areo Magazine

Julie Lenarz – Executive Director, Human Security Centre, London

Terry Sanderson President, National Secular Society

Greg Lukianoff, CEO and President, FIRE

Thomas Cushman, Professor Wellesley College

Nadine Strossen, John Marshall Harlan II Professor of Law, New York Law School

Simon Cottee, the Freedom Project, Wellesley College

Paul Cliteur, professor of Jurisprudence at Leiden University

Lino Veljak, University of Zagreb, Croatia

Lalia Ducos, Women’s Initiative for Citizenship and Universals Rights , WICUR

Lepa Mladjenovic, LC, Belgrade

Elsa Antonioni, Casa per non subire violenza, Bologna

Bobana Macanovic, Autonomos Women’s Center, Director, Belgrade

Harsh Kapoor, Editor, South Asia Citzens Web

Mehdi Mozaffari, Professor Em., Aarhus University, Denmark

Øystein Rian, Historian, Professor Emeritus University of Oslo

Kjetil Jakobsen, Professor Nord University

Scott Griffen, Director of Press Freedom Programmes International Press Institute (IPI)

Henryk Broder, Journalist

David Rand, President, Libres penseurs athées — Atheist Freethinkers

Tom Herrenberg, Lecturer University of Leiden

Simone Castagno, Coordinamento Liguria Rainbow

Laura Caille, Secretary General Libres

Mariannes Andy Heintz, writer

Bernice Dubois, Conseil Européen des Fédérations WIZO

Ivan Hare, QC[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1495443304735-e4b217b9-25e4-0″ taxonomies=”88, 53″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] Few people take religion less seriously than the Danes.

Few people take religion less seriously than the Danes.

Only 19% consider religion to be an important factor in their day to day lives. While some 76% remain members of the state church, that figure is down from 83% in 2006, and more than 24,000 people left the institution last year. Church going remains popular at Christmas, weddings and baptisms, but many churches are almost empty on any given Sunday. Long gone are the days when criticising the doctrines of Lutheranism or the Lutheran state church would land you in prison (or on the scaffold). So it created quite a stir when in February a local prosecutor announced that a Danish man was being charged for violating Denmark’s blasphemy law, which has been dormant since 1971 and last resulted in a conviction in 1946. A move approved by Denmark’s chief prosecutor.

How was a dead letter such as the Danish blasphemy ban suddenly revived?

The first step was taken by the Danish Criminal Law Council, an expert body advising the Ministry of Justice. In 2015 it released a lengthy statement on the blasphemy ban arguing that the burning of holy books would still be punishable, despite the decades-long practice of emphasising the importance of free speech over religious feelings. However, suspiciously, the expert body omitted any reference to a case from 1997 in which a Danish artist burned the Bible on national television.

Back then a number of complaints from the public were dismissed by the chief prosecutor emphasising among other things the importance of freedom of expression. It is difficult to understand why this seemingly clear precedent was disregarded by the expert body. But it was this questionable interpretation that paved the way for bringing back from the dead a ban thought of as antiquated and incompatible with a secular liberal democracy by most Danes, and indeed by most Europeans, since only five EU-member states still have blasphemy bans on the books.

One of the reasons cited by the expert body for punishing the burning of holy books is the need to prevent religious extremists – at home and abroad – from instigating riots and violence as a result of having their religious feelings insulted. This is a deeply problematic argument in and of itself, but even more so in the context of Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten having been the target of at least four foiled terrorist attacks since publishing cartoons of the prophet Muhammad in 2005, the murderous attack on Charlie Hebdo in 2015 and the killings of atheists and free thinkers in Bangladesh. A blasphemy ban indirectly legitimizes the Jihadist’s Veto, rather than confronting it. It is not punishable – nor should it be – to burn the Danish flag as has happened repeatedly in protests against the cartoons both in Denmark and abroad. No one would dream of arguing that it should be a crime to burn the Communist manifesto, Burke’s Reflection on the French Revolution, or Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations even though communists, conservatives and classical liberals might view these works as essential to their identities and deeply held beliefs. In all likelihood one of the most frequently burned book of the 20th century was Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, which went up in flames all over the world as offended Muslims took to the streets. Offended Muslims were free to do so, while Rushdie had to spend years living underground.

While burning books is certainly a crude and primitive practice with deeply troublesome historical connotations, it is nonetheless a peaceful symbolic expression, that should be protected free speech, whether the content of the scorched paper is secular or religious. By solely protecting religious books against such desecration the Danish blasphemy ban not only violates free speech and equality before the law, it is also tantamount to victim blaming and a dereliction of duty on the part of a liberal society which in no uncertain terms should make clear to religious fundamentalists that they cannot hope to have democracies impose their religious red lines on the rest of society through threats, intimidation and violence.

This was a point made clear by both Norway and Iceland whose parliaments chose to abolish these countries’ respective blasphemy bans as a direct consequence of the attack against Charlie Hebdo.

It would be wrong however, to suggest that Denmark has succumbed to the will of Islamists in particular, rather than to a loss of faith in free speech in general. Last year Parliament adopted a bill prohibiting “religious teachings” that “expressly condone” certain punishable acts and allows the government to maintain a dynamic list of “hate preachers” barred from entering Denmark. These initiatives were the direct consequence of a documentary exposing radical imams in Danish mosques preaching that the punishment for adultery and apostasy is stoning. And the current government has also presented a bill that would criminalize the mere sharing of “terrorist propaganda” online and allow the police to block access to websites containing criminal material such as terrorist propaganda or racist content. These developments signal a marked shift in the Danish approach to free speech.

In the post-World War II era Denmark has with a few exceptions been a liberal democracy committed to the idea that freedom of expression was an essential tool in defeating extremism and totalitarian ideologies. But Denmark is turning towards a model of militant democracy where free speech is often seen as the problem rather than the solution, and as a hindrance rather than the foundation of social peace. The revival of the Danish blasphemy ban should therefore be seen in the wider context of a world where respect for freedom of expression is at its lowest level in 12 years, a development that has now affected even one of the global bastions and beacons of free speech.

Jacob Mchangama is director of Justicia, a Copenhagen think tank focusing on human rights and the rule of law[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1489139072253-6b7daeee-fe12-8″ taxonomies=”53″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Kurdish broadcaster Roj TV has lost another battle in its long and controversial fight to stay on air. Denmark’s Supreme Court last month ruled to uphold the ban on the Kurdish-language broadcaster, which had been transmitting programs from Denmark to Europe and the Middle East since 2004. Roj TV’s former director, Imdat Yilmaz has announced plans to take the case to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

The broadcaster had long been a sore spot in relations between Denmark and Turkey, with the latter viewing the broadcaster as a mouthpiece for the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) – which is considered a terrorist organisation by the US and EU. However Kurds – a minority group making up between 10 and 23 per cent of the Turkish population – have long felt the heavy hand of the Turkish state on their language and culture.

Since the station’s launch, Turkey’s radio and TV authority – the ominously named Radio and Television Supreme Council – made a number of formal complaints to Denmark against the broadcaster. These had, until 2010, been dismissed by Denmark’s Radio and Television Board on the basis that “contested clips do not contain, in the opinion of the Board, incitement to hatred due to race, nationality, etc. In more than one clip, democracy, democratic solutions, democratic revolution and the like are even mentioned.”

But in 2010, Danish authorities did bring criminal charges against Roj TV – on the grounds that it was promoting terrorism. Roj TV was then convicted in 2012 by the Copenhagen City Court.

But controversially, Denmark’s decision to prosecute Roj TV on these charges was detailed in a leaked official document. The diplomatic document appearing to describe a deal struck between Turkish authorities and the then Danish Prime Minister – offering the closure of Roj TV in exchange for Turkey supporting the appointment of the then Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen to NATO secretary general in 2009.

The document refers to the Danish Radio and Television Board’s failure to find incitement to hatred or violence in Roj TV’s content, and so urges for Danish authorities to “think creatively about ways to disrupt or close the station, should criminal prosecution prove unachievable in the short term.”

Also mentioned is the need for “…some new evidence or approach that can shield them against charges of trading principle for the former prime minister’s career.”

Rasmussen, who is now NATO secretary general, has denied agreeing to shut the station.

The Wikileak document can be read in full here.

Roj TV have admitted maintaining contacts with to the PKK, but deny they are a mouthpiece for the organisation, or that they received funding from it. The station’s former general manager, Manouchehr Tahsili Zonoozi, has previously commented: “We are an independent Kurdish broadcaster. Our job is to be journalists.”

Last month’s decision by Denmark’s Supreme Court marks a line of increasingly punitive rulings against the broadcaster. The legal battle started with just a fine in the Copenhagen City Court in 2012 – the court found no legal basis to follow the prosecution’s recommendation that the station’s broadcasting license be revoked.

The appeal to the Eastern High Court in 2013 saw its broadcasting rights confiscated indefinitely and the existing fine increased, causing Roj TV and its parent company to file for bankruptcy.

Now that the ruling has been upheld by Denmark’s Supreme Court, the station plans to take the case to the ECHR, with Roj TV’s former director Imdat Yilmaz telling Danish newspaper Arbejderen that he hopes “instead of connecting Roj TV to ‘terrorism,’ the court may relate it to ‘freedom of speech”.

Kurdish-language programmes were banned in Turkey until 2002 and, until 2008, Kurdish-language programs were restricted to 45 minutes per day. TRT 6, Turkey’s first Kurdish-language station and part of the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation, was launched in 2008 and broadcasts Kurdish programmes that promote the Turkish state and counter PKK.

This article was posted on April 3, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org