20 Jan 2022 | Greece, Media Freedom, News and features, Statements

The undersigned international media freedom and freedom of expression organisations today register their concern over the serious criminal charges levelled against two investigative journalists in Greece linked to their reporting on a major corruption scandal. Our organisations are following these two legal cases with utmost scrutiny given the obvious concerns they raise with regard to press freedom. Authorities must issue guarantees that the process is demonstrably independent and free of any political interference.

On 19 January, Kostas Vaxevanis, a veteran investigative journalist and publisher of the newspaper Documento, testified at the Special High Court on four criminal charges of conspiracy to abuse power through his newspaper’s reporting on the Novartis pharmaceutical scandal. Under the penal code, Vaxevanis faces five years of imprisonment if found guilty, with a maximum sentence of 20 years. His newspaper has condemned the criminal charges as a politically motivated attack aimed at silencing a media critic which unveiled the scandal.

Ioanna Papadakou, a former investigative journalist and television host, is set to appear before a court on 25 January on separate but similar charges of being part of a criminal organisation which conspired to fabricate news stories about the Novartis case and the so-called “Lagarde list”, including the alleged extortion of a businessman through critical coverage. Papadakou has rejected the case as “blatant violation of the rule of law”. A Greek MEP from the ruling party and the Board of Directors of the Panhellenic Federation of Journalists’ Union (POESY – PFJU) have both expressed concern about the prosecution of the journalists. Neither journalist has yet been formally indicted.

The summons of Vaxevanis and Papadakou to testify are part of a wider parliamentary investigation into allegations of political conspiracy and abuse of power involving Greek judge and politician Dimitris Papagelopoulos, a former deputy minister in the previous Syriza government. Papagelopoulos is accused of falsely incriminating political opponents through the Novartis pharmaceutical scandal. The probe, launched by the current New Democracy government, has in turn faced accusations of politicisation.

Our organisations are closely following this case. The criminal charges against Kostas Vaxevanis and Ioanna Papadakou are extremely serious and carry heavy prison sentences. The nature of the charges, their connection to investigative reporting on corruption, and the potential imprisonment of two journalists in an EU Member State, raise legitimate concerns regarding press freedom and demand utmost scrutiny. Until commenting further, we await more detailed information from the Special Investigator about the specificities of the charges against both journalists.

What is absolutely clear is that judicial authorities examining this matter must act with full regard for press freedom standards and the function of investigative journalism in democratic societies. Moreover, given the politicisation of the wider affair, it is essential that guarantees are in place to ensure that judicial authorities act with complete independence in this case. We will continue to closely monitor both cases and have submitted alerts to Mapping Media Freedom (MMF) and the Council of Europe’s platform for the safety and protection of journalists.

In the coming weeks, the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR) is due to publish the findings of our recent online press freedom mission to Greece. Our organisations are already increasingly concerned about the challenging climate facing independent journalism in the country, including vexatious lawsuits against journalists. Greece is firmly in the spotlight in terms of threats to media freedom. We sincerely hope these cases will not become a matter of major international concern.

Signed:

European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

Free Press Unlimited (FPU)

International Press Institute (IPI)

Index on Censorship

OBC Transeuropa (OBCT)

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

The Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation

14 Jan 2022 | Armenia, Greece, News and features, Turkey

Sevan Nişanyan at home in Samos

A prominent Turkish-Armenian academic faces deportation from Greece after being labelled an “undesirable foreigner” in what he sees as punishment for creating a database of Greek placenames and how they have changed through history.

Sevan Nişanyan, born in Istanbul in 1956, is a linguist and compiler of the hugely comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the Turkish Language.

In 2012, he wrote a blog post about free speech arguing for the right to criticise the Prophet Mohammed which incensed then prime minister and now president Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Speaking to Index in an interview at the time, Nisanyan said: “I received a call from [Erdogan’s] office inquiring whether I stood by my, erm, ‘bold views’ and letting me know that there was much commotion ‘up here’ about the essay. The director of religious affairs, the top Islamic official of the land, emerged from a meeting with Erdogan to denounce me as a ‘madman’ and ‘mentally deranged’ for insulting ‘our dearly beloved prophet’”.

The following year he was sentenced to 13 months in jail for his “insults”.

While in prison, he was further charged with violations of building regulations in relation to the village of Şirince in Turkey’s Izmir Province and particularly the mathematical research institute established there in 2007 by Ali Nesin and in which Nasanyan was heavily involved.

Nişanyan was charged with 11 violations of the code leading to a total prison term of more than 16 years.

At the time, he and others were convinced that this was a political case, because jail time for building code infringements is almost unheard of in Turkey and he was merely being punished for his earlier views and blog post.

In 2017, Nişanyan escaped from the Turkish low security prison where he was being held and travelled by boat to Greece, where he claimed asylum and was granted a temporary residence permit.

He has since been living on the island of Samos and married a Greek citizen in 2019. While there he successfully applied for an Armenian passport and dropped his asylum application.

Everything changed on 30 December 2021 when he was denounced by the Greek police as a national security threat. His supporters say his name was added to what is known as the EKANA list of undesirable foreigners, administered by Greece’s Ministry of Public Order. At a recent press conference, Nişanyan claimed the reasons for the inclusion of his name on the list is considered a state secret.

The fast-growing use of the EKANA list has been called a “particularly worrying development” by the European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs.

“The Ekana list has become a favoured tool of the Greek police, primarily used against refugees who are denied asylum,” says Nişanyan.

Nişanyan says he has no concrete idea why his own name is on the list but he can speculate.

“There have been all sorts of accusations of me working against Greek national ideas,” he says.

He suspects it may be related to his creation of the Index Anatolicus, “a website looking at the toponomy of placenames, the authoritative source on the name changes to 53,000 Turkish places”.

“I recently decided to expand into Greece, North Macedonia, and Armenia,” he says.

He recognises it is a sensitive issue. In 1923, Greece and Turkey agreed to a population exchange after the fall of the Ottoman Empire which saw 1.3 million people made refugees.

“A hundred years ago, none of the towns and hamlets in northern Greece had Greek names. I have been accused by lots of insignificant people that this was a grave betrayal of the Greek motherland. That is absurd.”

On 7 January, the court ordered Nişanyan’s release saying he presented no risk of fleeing but gave him 15 days to leave the country voluntarily. He appealed against the ruling but this was thrown out on Thursday 13 January, meaning he must now leave by 22 January or face forced deportation. His request to be removed from the EKANA list has also been turned down. Nişanyan has appealed both decisions with the Administrative Court of the First Instance in Syros.

Nişanyan claims he is not a threat and that deportation would be particularly harsh on his wife, who is seriously ill.

He believes he has also become persona non grata as a result of a less welcoming attitude towards foreigners in the eastern Aegean in recent years.

“There has been enormous panic and paranoia over the refugees. Three years ago, people in Samos were divided on the refugee issue. Now you can be literally lynched if you say anything positive about refugees. It is a huge emotional mobilisation against all refugees and not surprisingly, part of that hostility has been directed towards Westerners and the NGOs who have ‘invaded’ the islands over the past few years.”

Where can Nişanyan go?

“I am tired and getting old. My wife’s health is a huge disaster. My normal instinct would be to stay and fight as I have been a fighter all my life. Now I am a weary,” he says.

“My three grown children are in Turkey and I have property there. However, I cannot go back unless there is some sort of presidential pardon.”

“The reasonable thing would be to go to Armenia, sit out the storm and come back some time,” but says that his chances of getting back to Greece appear slim.

It is also unclear whether his wife will be well enough to accompany him.

Nişanyan hopes the government comes to it sense and reconsiders an “utterly stupid decision which was obviously taken at the instigation of a paranoid and ignorant police force”.

He says, “I don’t think ever in the history of this country has a person who has not committed any crime whatsoever been deported to Armenia, historically one of Greece’s closest friends. It doesn’t make any political sense.”

Nişanyan has also gained support from the Anglo-Turkish writer and Balkans expert Alev Scott.

Scott told Index, “It is ironic that Sevan is hated in Turkey as an Armenian and in Greece as a Turk – and in both countries, as an outspoken intellectual who challenges conservative beliefs and nationalist sensibilities.

“He fled from a Turkish prison to a Greek island and embraced it as his new home; sadly, in recent years the Greek islands have become more and more hostile to foreigners as the refugee crisis worsens, and Sevan is a victim of this development.

“He is a big local presence on Samos, and receives a steady stream of visitors from Turkey and elsewhere – clearly, this has not gone down with locals, or with police,” she said.

“Sevan’s scholarly work on the etymological roots of place names raised hackles in Turkey and his proposal of a similar project on Greek place names has had a similar effect. Anything that challenges the existing nationalist narrative in both countries is, of course, highly controversial. It is beyond absurd that this academic – outspoken though he may be – presents a national security threat to Greece.”

Nişanyan also claims support for his case at the highest levels in the country – “former prime ministers, people high up in the judiciary system and journalists”.

“They seem shocked,” he says. “They cannot imagine something like this happening in a presumably democratic country.

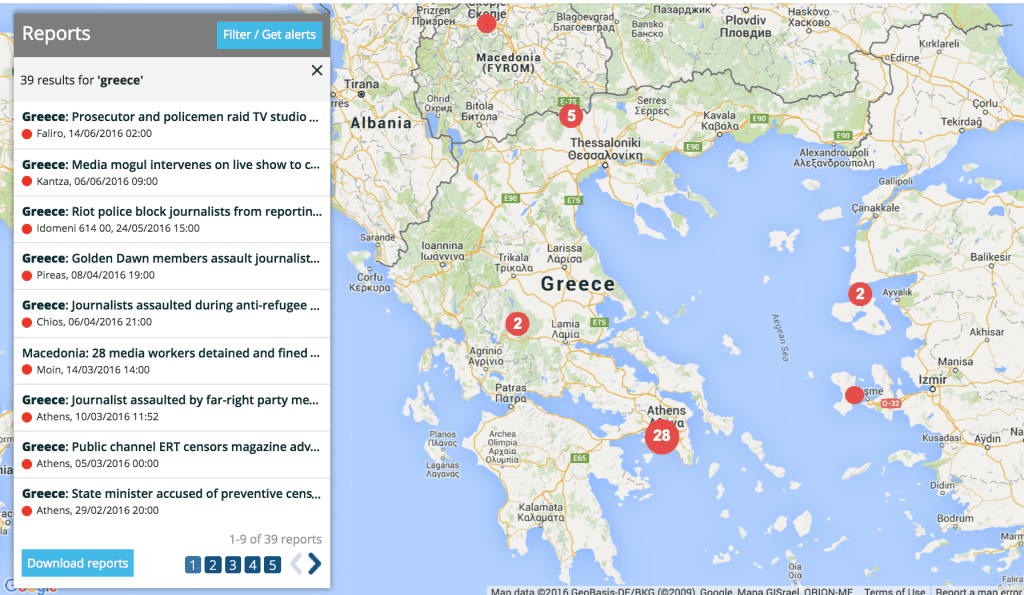

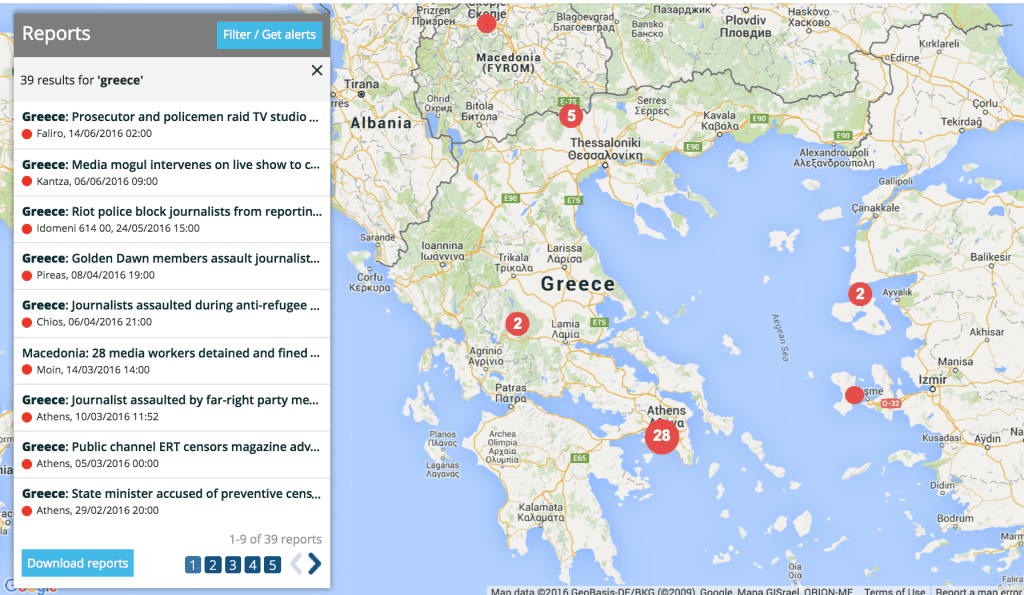

15 Dec 2017 | Greece, Mapping Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”96965″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://mappingmediafreedom.org/#/”][vc_column_text]Despite an ongoing trial that has sapped its popular appeal, members of the Greek press are still under pressure from neo-Nazi, far-right organisation Golden Dawn. Journalists have been targeted with libel charges and physical violence.

Two journalists working for the Ethnos newspaper, Maria Psara and Lefteris Bidelas, who revealed criminal activity associated with Golden Dawn, are facing a lawsuit demanding €300,000 ($352,377). The next hearing in the case, which was filed by Golden Dawn MP Ilias Kasidiaris, is scheduled for 14 December 2017.

“[Golden Dawn] are seeking our moral and economic extermination. They want us to stop writing,” Psara told Index on Censorship’s project Mapping Media Freedom, explaining that due to delays in the Greek legal system, these procedures normally may last for years, obliging journalists to spend days in courts.

The case stems from a physical assault on New Democracy MP Giorgos Koumoutsakos, which took place during a November 2015 protest in Athens, Psara and Bidelas explain. The perpetrators of the violence were allegedly a group of far-right supporters. In a news article about the incident, journalists Psara and Bidelas published an information coming from Koumoutsakos, that an eyewitness had called his office on that evening and had stated that he had heard the Kasidiaris tell a man to attack Koumoutsakos. Further, according to the account, the witness said that Kasidiaris shouted “Finish! Finish!” to the group as they were assaulting Koumoutsakos.

According to Psara and Bidelas, they published what Koumoutsakos told them about the incident during a conference call with the CEO of the newspaper, following his report to the police. Kasidiaris denied the allegations and filed a libel suit, naming the journalists and the CEO of the newspaper as defendants.

Constant pressure

Psara and Bidelas told MMF that this is not the first time that far-right supporters have targeted them. Around ten lawsuits have been filed against them in criminal and civil courts. In another ongoing libel case against them a Greek police commander sued the journalists for publishing a September 2014 photograph of the officer sieg heiling in front of a Nazi train at the Nuremberg Transportation Museum. The journalists were found guilty in a civil case and charged with a fine of €3,000 ($3,525) each. An appeal is scheduled for February 2018.

“I began to cover Golden Dawn in 2012 when its chief, Nikos Michaloliakos was elected a municipal councilor in the City of Athens,” Psara says, adding that the first time Golden Dawn reacted to a story of hers was in 2013. “It was a story about Golden Dawn members assaulting the actors of a play called Jesus Christ Super Star.”

The targeting of Bidelas began after the murder of the anti-fascist rapper Nikos Fyssas in 2013. Following an investigation into the murder, Michaloliakos along with several other Golden Dawn MPs and members were arrested and held in pre-trial detention on suspicion of forming a criminal organisation. The trial began on 20 April 2015 and is still ongoing.

At the time, Psara and Bidelas published articles that revealed the structure of Golden Dawn as well as the group’s racist and violent activities. Among their sources were ex-Golden Dawn members, which annoyed the organisation’s leadership. “They were calling at the newspaper to complain and insult us. Sometimes they even threatened us,” Bidelas says.

Golden Dawn’s popularity grew in the aftermath of the Greek financial crisis and the backlash created by the refugee crisis that swept Europe. The party managed to enter the Greek Parliament in 2012 with 21 seats, which emboldened them to openly attack the entire political system. Journalists became one of their main targets.

“Fear is a key element in the Golden Dawn ideology,” Psara told MMF. “They have attacked journalists physically, including during protests, as well taking legal action against them. The aim was to instil fear and stop any negative reports. In other words, they were abusing justice in order to serve their political interests.”

Over the last two years, examples of physical assaults against journalists and photographers have not been in short supply, as recorded by Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project. Journalists covering the refugee crisis often fell victim to far-right attacks. In response to these co-ordinated attacks, many journalists began to develop a common front against Golden Dawn.

“We had the absolute support of the newspaper and, when we made public the threats we were receiving, the support of our Union (ESIEA),” Bidelas says. “The support of individual colleagues was also touching.”

“We are definitely not the only ones in this. Many other journalists who dared to reveal the real face of Golden Dawn have become targets,” Psara says. “But what must be stressed it that we won’t bow to this pressure.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified more than 3,700 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Jul 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Greece, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

As Greece tries to deal with around 50,000 stranded refugees on its soil after Austria and the western Balkan countries closed their borders, attention has turned to the living conditions inside the refugee camps. Throughout the crisis, the Greek and international press has faced major difficulties in covering the crisis.

“It’s clear that the government does not want the press to be present when a policeman assaults migrants,” Marios Lolos, press photographer and head of the Union of Press Photographers of Greece said in an interview with Index on Censorship. “When the police are forced to suppress a revolt of the migrants, they don’t want us to be there and take pictures.”

Last summer, Greece had just emerged from a long and painful period of negotiations with its international creditors only to end up with a third bailout programme against the backdrop of closed banks and steep indebtedness. At the same time, hundreds of refugees were arriving every day to the Greek islands such as Chios, Kos and Lesvos. It was around this time that the EU’s executive body, the European Commission, started putting pressure on Greece to build appropriate refugee centres and prevent this massive influx from heading to the more prosperous northern countries.

It took some months, several EU Summits, threats to kick Greece out of the EU free movement zone, the abrupt closure of the internal borders and a controversial agreement between the EU and Turkey to finally stem migrant influx to Greek islands. The Greek authorities are now struggling to act on their commitments to their EU partners and at the same time protect themselves from negative coverage.

Although there were some incidents of press limitations during the first phase of the crisis in the islands, Lolos says that the most egregious curbs on the press occurred while the Greek authorities were evacuating the military area of Idomeni, on the border with Macedonia.

In May 2016, the Greek police launched a major operation to evict more than 8,000 refugees and migrants bottlenecked at a makeshift Idomeni camp since the closure of the borders. The police blocked the press from covering the operation.

“Only the photographer of the state-owned press agency ANA and the TV crew of the public TV channel ERT were allowed to be there,” Lolos said, while the Union’s official statement denounced “the flagrant violation of the freedom and pluralism of press in the name of the safety of photojournalists”.

“The authorities said that they blocked us for our safety but it is clear that this was just an excuse,” Lolos explained.

In early December 2015, during another police operation to remove migrants protesting against the closed borders from railway tracks, two photographers and two reporters were detained and prevented from doing their jobs, even after showing their press IDs, Lolos said.

While the refugees were warmly received by the majority of the Greek people, some anti-refugee sentiment was evident, giving Greece’s neo-nazi, far-right Golden Dawn party an opportunity to mobilise, including against journalists and photographers covering pro- and anti-refugee demonstrations.

On the 8 April 2016, Vice photographer Alexia Tsagari and a TV crew from the Greek channel E TV were attacked by members of Golden Dawn while covering an anti-refugee demonstration in Piraeus. According to press reports, after the anti-refugee group was encouraged by Golden Dawn MP Ilias Kasidiaris to attack anti-fascists, a man dressed in black, who had separated from Golden Dawn’s ranks, slapped and kicked Tsagari in the face.

“Since then I have this fear that I cannot do my work freely,” Tsagari told Index on Censorship, adding that this feeling of insecurity becomes even more intense, considering that the Greek riot police were nearby when the attack happened but did not intervene.

Following the EU-Turkey agreement in late March which stemmed the migrant flows, the Greek government agreed to send migrants, including asylum seekers, back to Turkey, recognising it as “safe third country”. As a result, despite the government’s initial disapproval, most of the first reception facilities have turned into overcrowded closed refugee centres.

“Now we need to focus on the living conditions of asylum seekers and migrants inside the state-owned facilities. However, the access is limited for the press. There is a general restriction of access unless you have a written permission from the ministry,” Lolos said, adding that the daily living conditions in some centres are disgraceful.

Ola Aljari is a journalist and refugee from Syria who fled to Germany and now works for Mapping Media Freedom partners the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom. She visited Greece twice to cover refugee stories and confirms that restrictions on journalists are increasing.

“With all the restrictions I feel like the authorities have something to hide,” Aljari told Index on Censorship, also mentioning that some Greek journalists have used bribes in order to get authorisation.

Greek journalist, Nikolas Leontopoulos, working along with a mission of foreign journalists from a major international media outlet to the closed centre of VIAL in Chios experienced recently this “reluctance” from Greek authorities to let the press in.

“Although the ministry for migration had sent an email to the VIAL director granting permission to visit and report inside VIAL, the director at first denied the existence of the email and later on did everything in his power to put obstacles and cancel our access to the hotspot,” Leontopoulos told Index on Censorship, commenting that his behaviour is “indicative” of the authorities’ way of dealing with the press.