5 Dec 2017 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, Montenegro, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”96761″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]This article was originally published by Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso.

Read in Italian.

Jovo Martinović is a freelance investigative journalist in Montenegro, who has worked for a number of international outlets — National Public Radio, BBC, VICE, CBS, Canal Plus, The Economist, TIME, Global Post, BIRN — and is known for his reports on organised crime in Europe and war criminals in the Balkans. His investigations brought him in close contact with persons involved in drug-trafficking as well as members of the Pink Panthers, an international network of jewellery thieves.

In October 2015, he was arrested after being charged with drug trafficking and participation in a criminal organisation. The prosecution by the Montenegrin state – as well as the long, unjustified pre-trial detention – was highly criticised by international media freedom and human rights organisations. Martinović proclaimed his innocence and – as a well-known, respected investigative journalist – could convincingly state that the contacts were part of his investigation.

Martinović was released at the beginning of 2017 after 14 months in prison, but is still on trial, facing up to ten years in prison. Francesco Martino, a correspondent for Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso, met him in Pristina, during a conference organised by Le Courrier des Balkans.

Do you see your case as unique, or as part of a general strategy to undermine freedom of the press in Montenegro?

In Montenegro, in these last years, several cases were registered of physical attacks against journalists, and in 2013 the premises of the leading independent newspaper Vijesti were bombed. So, yes, the media and journalists have been under pressure in Montenegro. My personal case was somehow different, probably because I have always worked for the Western media. The approach taken against me was definitely unique: no other journalist in Montenegro has spent fourteen and a half months in prison. Cases like mine have been registered in countries like Russia, Turkey, and Venezuela, where last year investigative journalist Braulio Jatar was accused of money laundering and imprisoned after appearing as an opponent of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro.

In the past, were you ever “warned” to stop your investigations by representatives of the political power?

I was warned – to put it that way – several times in the past, when I worked in some investigations that were not particularly well-received, to say so. Sometimes, I was even suspected for reports which appeared in the foreign media that I had nothing to do with.

How were you treated during your long imprisonment?

I was treated fairly during my stay in prison. While filming a documentary film on the main defendant in my case, Dusko Martinović, I had been several times in prison to interview him, so they already knew me there. I enjoyed a fair treatment, and I didn’t receive any pressure from the prison staff while being detained.

How do you explain your incarceration? Which are the reasons for such a long time behind bars?

When I was arrested, I was working on a documentary film for the French channel Canal Plus about smuggling of weapons from the Balkans – Albania and Bosnia and Herzegovina in particular – into France, weapons that eventually ended up in the hands of terrorist groups. Back then, I was working on the Bosnian case and filming in Serbia, so our investigation wasn’t linked to Montenegro at all. I find it difficult to link it with my incarceration unless we’re speaking of pure communist paranoia on the part of someone in power. I rather believe that they used the documentary as an opportunity for pay-back for my non-compliance and “insubordination” in earlier cases.

You have always worked for international media rather than for local ones. Do you think this puts you in a more delicate position?

Yes, sure. Balkan governments are much more scared and worried about what big international media report about them than the local ones. So, working for international media puts you under a stronger pressure, because if governments or the security structures aren’t happy about the way a certain matter has been reported, the easiest way to retaliate is to put the blame on the local stringer.

What was the reaction of journalist’s organisations and the Montenegrin media to your arrest? Did you receive tangible solidarity?

Initially, local media picked the news from international organisations that wrote to the Montenegrin government on my behalf. In the beginning, the reaction was quite humble, maybe because I wasn’t really perceived as part of the Montenegro media community since, as I already stressed, I never worked for the local media. But when my incarceration was prolonged, Montenegrin independent media started to focus on my case and were very supportive. On the other hand, though, the state-controlled media basically ignored my story.

Do you think journalists and media in Montenegro are eager to support each other in defending freedom of speech in the country?

Montenegro is a small country with a small media market, so petty rivalries among journalists are quite common. Nevertheless, when it comes to serious matters like protecting media freedom, I think solidarity and mutual support prevail.

Is there any real room for investigative journalism in Montenegro? Are there concrete opportunities to denounce corruption, links between political power and organised crime, and effective channels to reach the public?

Sure, freedom of expression does exist and in these past years, some local media have done an extremely good job. There have been several good stories, scoops, which haven’t produced any big change in society yet. Of course, as in many other countries in transition, opportunities for good journalism in Montenegro are accompanied by risks and challenges. What’s worse, though, is that good investigations usually have no impact, even if they’re substantiated by facts and documents. In the Balkans, and particularly in such a small country as Montenegro, you don’t have the same public response to news criticising the government as in Western Europe. I think this is partly explained by a weaker democratic tradition.

Montenegro is currently an EU candidate state: do you think the European monitoring linked with accession negotiations is helping to improve media freedom in the country?

It’s difficult to give a clear-cut answer, but I believe the EU is generally playing a positive role. Endorsing a Western system of values in the framework of the EU accession process is relatively easy, while it’s way more challenging to actually implement those values, transforming Balkan countries into viable realms of rule-of-law.

This publication has been produced within the project European Centre for Press and Media Freedom, co-funded by the European Commission. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso and its partners and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The project’s page[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1512410060523-0e52f5ac-262f-7″ taxonomies=”9043, 4612″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Feb 2017 | Croatia, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, Montenegro, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Independent journalist Jovo Martinovic’s arrest with 13 other individuals during a joint Croatian and Montenegrin police operation on 22 October 2015 began an ongoing ordeal.

Martinovic was taken into custody “on reasonable suspicion that he committed criminal offence – creation of criminal organisation and unauthorised production, possession and distribution of narcotics”, according to Montenegro’s ministry of justice. Media reports explained the case more colloquially: Martinovic was detained for allegedly facilitating a meeting between drug dealers and buyers, and helping them to install a messaging app on their smartphones that is allegedly untraceable by the police.

Following Martinovic’s arrest, it took more than five months for the Special Prosecutor’s Office to raise an indictment against him. Then he spent an extra six months in pre-trial detention before the court case began on 27 October 2016. In total, Martinovic, who insists he is not guilty and the contacts with the suspects spent around one year in jail before the trial even took place. He was conditionally released on 4 January 2017. He remains under a travel ban and must report to police twice a month until the court’s final verdict is issued.

The length of Martinovic’s pre-trial detention provoked OSCE representative on freedom of the media Dunja Mijatovic and other watchdog organisations to call for a swift conclusion of his case. “Prolonged detention can have a detrimental impact on media freedom and a chilling effect on investigative journalism,” Mijatovic said.

The Committee to Protect Journalists, Human Rights Watch and Reporters Without Borders wrote a joint letter to Montenegrin prime minister Milo Djukanovic protesting the prolonged pre-trial detention and prosecution. The International Federation of Journalists wrote a letter to Djukanovic stating that they were “shocked by the gravity of his possible sentence being more than 10 years in prison”. Journalists who have worked with Martinovic wrote testimonies that in support of his professional integrity.

Martinovic has insisted that he is not guilty, adding that his contact with the two of the 13 suspects was linked to his journalistic work.

The main suspects, Dusko Martinovic (no relation) and Namik Selmanovic, who is co-operating with prosecutors, were helping the journalist in his reseatch for two documentaries, firstly a Vice documentary on the infamous Pink Panthers, a gang of gem thieves, and La Route de la Kalashnikov, a documentary about weapons smuggling commissioned by French production company CAPA Presse. The second programme, which exposed illegal smuggling of weapons from the Balkans into western Europe, was aired on the French television channel Canal+.

During one of the court sessions, Dusko Martinovic testified that met Martinovic for the first time in 2012 while he was serving time in prison for crimes related to his membership in the Pink Panthers. He also testified that the journalist had no involvement in illegal activities.

“Jovo did not take part in any drug smuggling operation,” Dusko Martinovic said in the court, Montenegrin daily Vijesti reported. In its coverage, the newspaper reported that Dusko Martinovic stressed that his contacts with Martinovic were strictly connected with the VICE documentary and later for a possible Hollywood movie about the Pink Panthers. Dusko Martinovic also said that he was offered a plea bargain by prosecutors if he testified “that Jovo was included in the drug smuggling”.

The one-year detention of Martinovic has raised questions about the country’s commitment to freedom of the press, Human Rights Watch associate director for program Fred Abrahams wrote: “The start of his trial last week did nothing to allay those concerns. To date, the evidence against Martinovic offered by deputy special prosecutor Mira Samardzic is weak, at best. She has allegedly incriminating statements from two of Martinovic’s co-accused, both of whom face jail sentences and have an incentive to co-operate with prosecutors. She also has recorded phone conversations between Martinovic and the alleged gang leader, Dusko Martinovic (no relation), but defence lawyers and others who have read the transcripts say they contain nothing to incriminate Jovo.”

Once free, it was much easier for Martinovic to tell his side of the story. Speaking to Mapping Media Freedom in a limited capacity about the ongoing case he said: “I do reject with indignation the charges laid against me. I was doing my job as a reporter and that is an undeniable fact.”

Martinovic said that until the trial ends he won’t be giving other statements.

“I will fight in court to the utmost to defend my innocence”.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

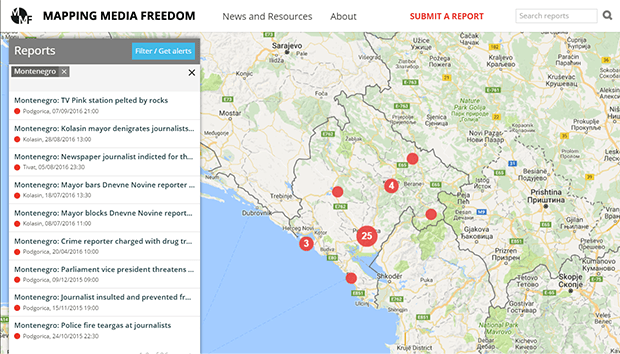

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1490287936930-99f1d6d4-195c-1″ taxonomies=”256, 4612″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Sep 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, Montenegro, News and features

In the past two months three threats to media freedom involving the mayor of Kolasin, a town in Montenegro, have been reported to Mapping Media Freedom.

Kolasin, which is the centre of a regional municipality of about 10,000 people, has a small media market that includes just one local newspaper named Kolasin and four correspondents working for the national dailies — Pobjeda, Dan, Vijesti and Dnevne Novine. There is no local TV station. The local government is run by a coalition of opposition parties — Democratic Front, the Social Democratic Party of Montenegro (SDP) and the Socialist People’s Party of Montenegro — while the Democratic Party of Socialists is the majority party in the national parliament and it runs the Government.

|

This article is a case study drawn from the issues documented by Mapping Media Freedom, Index on Censorship’s project that monitors threats to press freedom in 42 European and neighbouring countries.

|

|

In two of the cases, the local official, Zeljka Vuksanovic, an opposition politician belonging to SDP, had intentionally not invited Zorica Bulatovic, Kolasin correspondent for the governing party-aligned daily newspaper Dnevne Novine, to press conferences. In the third case, Bulatovic reported that she was verbally harassed.

Bulatovic told MMF that she is being blocked from reporting on Kolasin’s administration as a result of her critical reporting. In a statement to MMF, the mayor said that Bulatovic’s politically motivated reporting is the reason the journalist is not being invited to press conferences. “If you read her articles you will see why I am not communicating with her. You will see that those articles are not articles written by a journalist,” Vuksanovic wrote.

According to CDM, a media outlet owned by the Greek businessman Petros Stathis, who also owns the Dnevne Novine and another daily, Pobjeda, Bulatovic was not invited to an 8 July press session organised by the municipality. The news outlet also reported that Vuksanovic forbid municipality departments from cooperating with or providing information to Bulatovic.

Ten days later, on 18 July, the reporter was the only local journalist not included in a press conference organised after the visit of the national government’s minister for human and minority rights, Suad Numanovic, who called on officials to reverse their decision regarding Bulatovic.

The third incident occurred on 28 August when, in a speech, Vuksanovic said that the local ruling coalition had succeeded in triumphing over “crime, political corruption and media sputum”. Incensed by the speech, the five reporters that were present asked the mayor for an apology and further clarification on her points. The following day, Vuksanovic addressed her reply to four of the journalists, again omitting Bulatovic.

In the response, the mayor said that the term “media sputum” was not directed to the four journalists, but to the “media sputum that is hiding behind journalism as a profession”.

“It’s clear from the incident that the ‘media sputum’ comment was in fact verbal harassment of Zorica Bulatovic,” MMF project officer Hannah Machlin said. “This type of comment only serves to undermine the press as whole.”

Bulatovic told MMF that the negative climate between herself and the mayor has been going on for two years. She said that not only is she facing closed doors at the mayor’s office, but also at the municipal administrations.

The mayor disagrees with Bulatovic’s assertions, saying that the journalist is not barred from attending press conferences. “It is true that I don’t send her invitations for the press conferences, but I have never physically banned her presence at the press center,” Vuksanovic wrote MMF in an email.

Bulatovic maintains that she is barred from entering the press center. She also said that in the five years she has been reporting for Dnevne Novine, she has not had to make any corrections to her articles.

While Bulatovic is facing daily obstacles to her reporting, the four other local journalists are in a slightly better position since they are invited to press conferences. Yet, according to her, all the journalists face a common problem: despite the 2012 freedom of information law local politicians consistently throw up obstacles to documents or sources that would put them in a negative light.

“This whole situation is enormously impacting my work because it’s impossible for me to get an official statement from the local municipality,” Bulatovic said.

(Self)censorship always happens to someone else

Marijana Camovic, a journalist and head of the Trade Union of Media of Montenegro, said that while she was not fully aware of the situation in Kolasin, she did not know of another case where a reporter has been under a constant ban from press conferences. The usual practice for Montenegrin politicians is to publicly denigrate the work of journalists who are putting them and their administrations under scrutiny.

Camovic said the issue journalists in small communities with limited news sources, like Kolasin, most often grapple with is self-censorship.

“I personally think that self-censorship is an even bigger problem than censorship, as in that circumstance journalists know what is expected from them to write,” she said.

In her experience, it is rare for a journalist to be openly censored by their editor. The union recently undertook research, which will be published in October, that amongst other things asked journalists to comment on censorship and self-censorship in Montenegro. Camovic called the preliminary results very interesting.

“Generally, journalists answer that there are self-censorship and censorship in Montenegro. But, when you asked them whether they have personally been censored or succumbed to self-censorship, then only a few of them answer positively. So the conclusion is that there are self-censorship and censorship, but it always happens to someone else, which is paradoxical in itself,” Camovic said.

Her hypothesis is that journalists are probably ashamed to admit that they adjust to the official media policy to keep their jobs. It is not a secret that media outlets are politically engaged, she said.

“They openly support one and criticise the other political option. This is done without consideration of ethics and the role of the media in the democratic society.”

13 Oct 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, Montenegro, News and features

While the physical safety of Montenegro’s journalists is far from guaranteed, a more troubling trend toward using media professionals to settle professional or business scores is undermining the country’s news outlets.

Describing mass media in Montenegro, Marijana Camovic, a journalist and head of the Trade Union of Media, says the deep-rooted division between pro-government and pro-opposition media has now reached a completely new level. Television news and newspaper front pages are filled with the “dirty laundry” of journalists that work for competing outlets, she said.

As a result of the smear campaigns, more journalists are leaving the profession.

“Before, journalists would consider leaving the job only after they found a new one, but not anymore. Nowadays there are a lot of displeased and disappointed journalists who are quitting without thinking twice.”

These departures leave empty spaces that are filled by people who are willing to work for lower wages and compromise on journalistic integrity by publishing what they are told to publish. Ethical and professional journalism is becoming scarcer, according to Camovic.

Without proper media ethics and professional solidarity, journalists are often manipulated by politicians and businessmen to advance the cause of interests contrary to their own or the public’s, says Camovic. “Media workers are being used as a tool for political pressure and the elimination of other political affiliations.”

At the same time, there has been a drastic decrease in circulation, lower advertising income and growing debts for outlets. Camovic said the Montenegrin media’s catastrophic economic condition can no longer be denied.

Camovic points out that the main issues affecting media professionals are no longer impunity or physical assaults. Today, the major areas of concern include a lack of respect for media workers’ rights and falling salaries; fair remuneration for freelancers; and the rights to unionise and collective bargaining.

However, this is not to say that journalists’ safety is no longer an issue. Take, for example, the case of Tufik Softic, who has been under constant police protection since February 2014. In November 2007, Softic was brutally beaten in front of his home by two hooded assailants wielding baseball bats, and in August 2013, an explosive device was thrown into the yard of his family home. The European Federation of Journalists (EFJ) sent an open letter to Filip Vujanovic, president of Montenegro, in June this year expressing their “regret that no concrete action has been done to bring the perpetrators, who are behind these attacks, to justice”.

As Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project highlights, the tactics of intimidation have shifted. Between February 2014 and October 2015, there were 23 verified media violations in Montenegro. Most of those incidents involved attacks on journalists’ property, with cars being a popular target.

Last year, Human Rights Action (HRA) outlined in a report that there were 30 instances of threats, violence and murder, as well as attacks on media property between May 2004 and January 2014.

“I think that everything should be changed – from the approach towards journalism to the dynamics inside the guild,” she says. But the biggest mistake, Camovic emphasises, is that journalists are taking part in the blackmailing game, which has resulted in the absolute collapse of professional standards.

Camovic points to the almost uninterrupted 24-year political rule of Milo Dukanovic, the passivity of Montenegrin society and the absence of the rule of law as contributing to the dire situation.

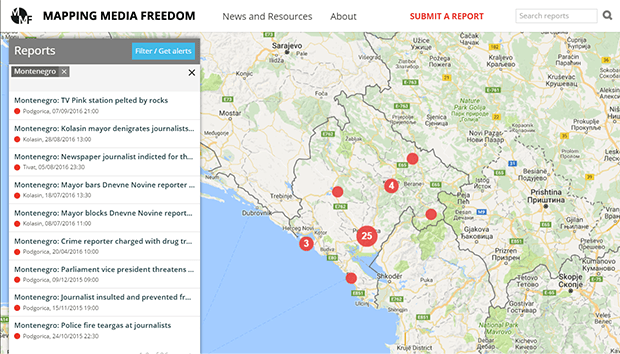

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|