Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Bartomeu Marí at the charity launch of a calander at the MACBA, from which he controversially resigned earlier this year. Credit: Flickr/Mossos. Generalitat de Catalunya

The South Korean art community has released a statement requesting that the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (MCST) implement reforms to protect artistic freedom ahead of the appointment of Bartomeu Marí as director of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA).

The decision to appoint Marí has been met with objections due to his controversial resignation as director of the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art (MACBA) in March, after he was accused of attempting to have a sculptor removed from an exhibition called La Bestia y el Soberano (The Beast and the Sovereign).

The satirical sculpture by Ines Doujak, titled Not Dressed for Conquering, featured former Spanish King Juan Carlos and Bolivian labour leader and feminist Domitila Chúngara involved in a sexual act with a dog on a bed of SS helmets. The exhibition went ahead despite Marí’s alleged attempts to cancel the whole exhibition when curators refused to remove the sculptor, leading to him firing two curators and his own resignation.

The Korean art community released their statement in November when Marí was the leading candidate for the position. They stated: “We demand that both the MMCA and its overseeing body, the MCST, offer plausible explanations regarding the appointment of the new MMCA director and institute fully fledged reforms to protect and foster artistic freedom so they may perform the duties they were originally intended as proponents of the arts.”

They also used the statement, which has been signed by nearly 800 artists, to highlight their concerns about the South Korean government’s mounting censorship of and bureaucratic restrictions on artistic freedom. They state: “We strongly oppose all variants of censorship and surveillance that harm the autonomy of art, and we pledge multifaceted, continued efforts to recover the autonomy and independence of art.”

Marí, who is also currently the president of the International Committee for Museums and collections of Modern Art (CiMAM), was officially appointed as director on 2 December leading the group to release a new statement again asking the newly appointed director and the MCST institute reforms protecting artistic freedom, which would be submitted to the culture minister and director on his appointment today.

The new director took nearly two weeks to respond to the complaints by stating he opposes censorship of any kind. He told a press conference in Seoul: “I stand against all kinds of censorship, and I support the freedom of expression. These are my values.”

He added: “I am sad there are artists who opposed my nomination. But there are many who support me. I hope I can be judged by what I do here, not by what some people say happened in the past.”

(Image: Aleksandar Mijatovic/Shutterstock)

South Korean prosecutors currently seeking a whopping 20 years imprisonment for lawmaker Lee Seok-ki on charges including praising North Korea. On 3 February, the Korean Supreme Court overturned a partial acquittal of a man charged with praising North Korea; that same day a 74-year-old man was given a sentence of two-and-a-half years for similar activities. On 28 January a man was sentenced to ten months in prison for posting pro-Pyongyang messages in an obscure online cafe.

These are some of the latest in a spate of recent cases which indicate that the South Korean government is more strictly enforcing its controversial National Security Law (NSL). Article 7 of the law long criticised as an unjust limit to freedom of expression, prescribes legal punishment for “any person who praises, incites or propagates the activities of an anti-government organisation”. What constitutes praise, incitement or propagation is not clearly defined.

While supporters say the NSL is necessary to protect a fragile peace against the North Korean threat, critics say the threat of North Korean infiltration is exaggerated and the law is really meant to stifle dissent within the country. Amnesty International said the NSL is “increasingly and arbitrarily used to curtail freedoms of association and expression”, while the United Nations special rapporteur for human rights defenders, Margaret Sekaggya, described the NSL as “seriously problematic for the exercise of freedom of expression”.

Recent years have seen cases where seemingly innocuous conduct led to criminal prosecution, notably the case of Park Jung-geun, who was indicted in 2012 on criminal charges for retweeting messages from North Korea’s official Twitter account. Between 2008 and 2011, the number of NSL cases shot up by 95.6 percent, according to an Amnesty report released in December 2012. Last year 103 people were charged with violating the law, the highest figure in ten years.

The charges against Lee Seok-ki were laid in spring of last year when Seoul and Pyongyang were engaged in a war of words that had many wondering if actual war was imminent. The main charge against him is making plans to help North Korea win in the event of a war. However, he is more likely to be convicted according to the NSL for praising North Korea at a meeting, referring to North Korea’s leadership using honorific titles. To be convicted of assisting North Korea during a war prosecutors would have to show that Lee’s plans were practicable, which is unlikely.

The NSL was instituted in the late 1940s, in the time between Korea’s colonial occupation by Japan and the start of the Korean War, ostensibly to protect South Korea from infiltration by North Korean spies. The combat phase of the Korean War ended with an armistice agreement in 1953, but no peace treaty was ever put in place, so the two countries technically remain at war. This enduring state of conflict has meant that the NSL has remained on the books as a limit to freedom of expression.

Throughout nearly all of its history, South Korea has been governed under something like a state of emergency, with the government arguing that due to the threat posed by North Korea, civil liberties needed to be suspended to maintain security and allow for economic development.

Last April, the country’s top legal authority, Justice Minister Hwang Kyo-ahn, defended use of the NSL in an interview with JTBC television. Hwang argued that pro-North Korea forces are plentiful in the South and that the NSL was needed as protection, saying: “A special kind of law is needed to defend against this special kind of crime”.

What Hwang didn’t mention is that the groups that voice these kinds of pro-North Korea statements are tiny, fringe outfits that almost no one takes seriously and have never had any real success. Critics say criminalising their statements only lends them an undue air of seriousness.

President Park Geun-hye and her cabinet are not a free speech-loving bunch, and are in office at a time of tense relations with North Korea, meaning that pro-North Korea activities are being taken seriously. Park herself is daughter of former South Korean president Park Chung-hee, a military dictator who suspended civil rights including freedom of speech in the name of national development.

The increased use of the NSL shows the durability of this logic, and the South Korean government’s steady position [means that] freedom of expression can be limited in the name of vague national objectives.

This article was posted on 12 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

South Korea is embroiled in a “textbook war” over what high school students learn in history class. With schools selecting their textbooks for the coming academic year, objections have been raised to one textbook that critics felt distorted the country’s history of Japanese occupation and military dictatorship. A storm of conflict has followed, raising questions over longstanding disagreements regarding how to interpret history, what young people should learn and who gets to decide on the material they study from.

The controversy started in September after the Ministry of Education gave tentative approval to a book written and published by a company called Kyohak, which is known for its right-wing leanings. After receiving tentative approval, the Kyohak book was selected for the 2014 academic year (which starts in March) by around 20 schools, a small portion of the 800 high schools nationwide.

Liberal critics argued that the textbooks misrepresented some aspects of contemporary South Korean history. In particular, they said the books painted an inaccurately rosy picture of Korea’s colonial occupation by Japan and provided an airbrushed account of the military dictatorships that held power from the 1960s through to the democratization movement of the late 1980s, when the government in Seoul softened up and agreed to elections before hosting the 1988 Summer Olympics.

The choice of the Kyohak books led to an outcry from left wing civic groups across the country, who protested at schools and government offices in an attempt to pressure the schools to cancel their selections. All but one of the 20 schools that selected the Kyohak books have since cancelled their orders for them and said they’ll use different books. The one school that hasn’t cancelled its selection is reportedly “reconsidering” its decision to use the Kyohak book in class.

But parents and activists on the other side of the political spectrum, who are more in line with the account of history presented in the Kyohak books, have argued that the liberal groups’ pressure to change the textbooks amounts to intimidation and an infringement on the schools’ rights to use the book of their choosing.

Kyohak called the campaign to keep its textbooks out of classrooms a “witch hunt” and argued that as the book had gained government approval, schools were free to select and use it if they chose.

The Ministry of Education then conducted an investigation into the schools that selected the Kyohak books and then changed their minds. It concluded that the cancellations were made due to “relentless criticism from civic groups”, as Deputy Minister of Education Na Seung-il said in a Jan. 8 press briefing.

If high school history textbooks seem like a silly thing to fight over, consider the lasting controversy over history in South Korea. The antagonism illustrated in this discussion of high school history textbooks is born of a deep, long-standing split in South Korean society: The country is still roughly divided over those who benefited from the Japanese colonial occupation (1910-1945) and those who were harmed by it. South Korean politics and media are still characterised by a left-right divide where the two sides agree on almost nothing and undermine anything associated with the other side.

In the controversy over the Kyohak books, and in discussions of South Korean history generally, the interpretation of the rule of former President Park Chung-hee (1961-1979) is a particular point of contention. After Korea became independent from Japan, Park used reparation money to establish the infrastructure and industrial base that made South Korea’s economic miracle possible. During his rule, he suspended nearly all civil liberties and ruled as a military dictator. Whether he should be remembered as a father of a successful nation or a brutal dictator who trampled on the nation’s rights is still a matter of heated debate. The Kyohak books were accused of highlighting only the benefits of his policies and ignoring the human cost.

This recent furor over Kyohak has also reignited a conversation that Park initiated when he was president. In 1974, he initiated a system whereby all schools nationwide used one official textbook, which allowed the government to control what students learned in school about their country’s history . The books told students that the coup d’etat that brought Park to power and the lack of rights enjoyed by South Korean citizens were necessary for the country’s security and advancement.

The system whereby all schools used one state-designated history textbook was ended in the mid-1990s and autonomy was granted to schools to select their own textbooks. Last week, members of the ruling Saenuri Party floated the idea of returning to the system of state-designated textbooks, ostensibly to avoid ugly episodes like the recent friction over the Kyohak books.

Current President Park Geun-hye is the daughter of Park Chung-hee. One year into her rule, many have accused her of reverting to dissent-quashing tactics that are reminiscent of her father’s time in power. The same critics who objected to the Kyohak books see the suggestion of state textbooks as opportunist move by the government, and an attempt to take control over what all young people learn.

This article was posted on 21 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

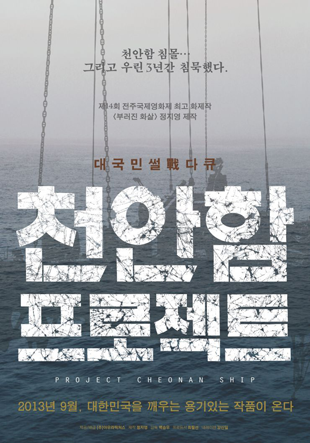

A recently released film in South Korea set out to spark a discussion on free speech in the country, and amid opposition and cancelled viewings, it has done just that.

A recently released film in South Korea set out to spark a discussion on free speech in the country, and amid opposition and cancelled viewings, it has done just that.

Project Cheonan Ship is a film on the aftermath of the 2010 sinking of the Cheonan warship, a South Korean navy submersible that went down in waters near North Korea. South Korea concluded that a North Korean torpedo was the cause of the sinking, though North Korea denied any involvement. The film features experts in a range of fields offering possible alternative causes of the ship’s sinking.

In August, members of the South Korean navy and relatives of a few of the 46 sailors who died in the sinking sought a court injunction to prevent the film’s release. “There is freedom of expression, but no freedom of distortion…If the movie is released, it could defame the reputations of the 46 fallen soldiers and their bereaved families”, the group’s lawyer said in a statement.

The injunction was denied in court and the film opened according to schedule on Sept. 5 at 30 theaters across South Korea, mostly in independent film houses but in a few major theaters as well. It did well on its opening weekend, ranked first among independent films and eleventh overall at the box office.

After two days, the film was pulled by Megabox, a major theater chain. This is believed to be the first time in Korean history that a film has been pulled in this way. Megabox said that they had received warning from conservative civic groups who planned to picket the theaters showing the film. The theater company said they didn’t want to put viewers’ safety at risk, and therefore stopped showing the film to avoid trouble.

A big part of the reason why the issue of the Cheonan sinking is still prickly is that there was a long debate over the cause of the sinking and though the evidence strongly points to North Korea, there still isn’t a uniform consensus on what happened. An international investigation commissioned by the South Korean government eventually concluded that indeed, a North Korean torpedo had sunk the Cheonan. Skeptics continued to argue that the ship could have come in contact with a mine leftover from the Korean War.

The debate over the sinking has been split along the lines of South Korea’s political divide: conservatives who support the South’s military alliance with the US and are bitterly opposed to North Korea, and those on the left who don’t approve of the large US military presence in South Korea and see it as the main obstacle to peaceful reunification with North Korea.

People in South Korea who voice either explicit or implied support or sympathy for North Korea are often shouted down. There is even a law banning expressions ofsupport for the North: Article 7 of the National Security Law (NSL) stipulates up to seven years in prison for anyone who “praises, incites or propagates the activities of an anti-government organization”. Under the law, North Korea counts as just such an anti-government organization.

While supporters say the NSL is necessary to protect a fragile peace against the North Korean threat, critics say it is a vaguely worded prohibition that is really meant to stifle dissent within the country.

The makers of Project Cheonan Ship intended not to take a position on the cause of the Cheonan sinking, but to start a conversation about the importance of unimpeded expression of differing views. “Our primary motivation was not telling a story about the Cheonan sinking case itself, but about the intolerant attitude seen in our society after the incident,” Director Baek Seung-woo said in an interview on Sept. 13.

Baek said he and the other filmmakers wanted to reiterate the importance of free speech in South Korea. “We made this movie because we believe most people in our society have an understanding of what free speech means, but don’t yet fully appreciate its value,” he said.

Even after making the film, they still don’t attempt to make definite claims on how and why the Cheonan went down. Baek explained, “While making the movie, I realized how extremely difficult the case was. I am not expert on marine science or military equipment or explosives. I’m not scientist either. I don’t know what the cause is, but I think the real experts in our society need a more open climate of free speech to really figure out what happened.”