[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Yanelys Nuñez Leyva and Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara. The Museum of Dissidence

2018 Freedom of Expression Awards at Metal, Chalkwell Park, Essex.

Artistic freedom is under attack in Cuba, but artists are fighting back. Yanelys Nuñez Leyva and Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, members of the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award-winning Cuban artist collective the Museum of Dissidence, along with many others, are putting themselves on the line in the fight against Decree 349, a vague law intended to severely limit artistic freedom in the country. Decree 349 will see all artists — including collectives, musicians and performers — prohibited from operating in public places without prior approval from the Ministry of Culture.

“349 is the image of censorship and repression of Cuban art and culture, and is also an example of the exercise of state control over its citizens,” Otero Alcántara tells Index. “Artists, in a spectacular way, must work in a state of double resistance, as artists and as activists, because the system has control over all opportunities for artistic growth.”

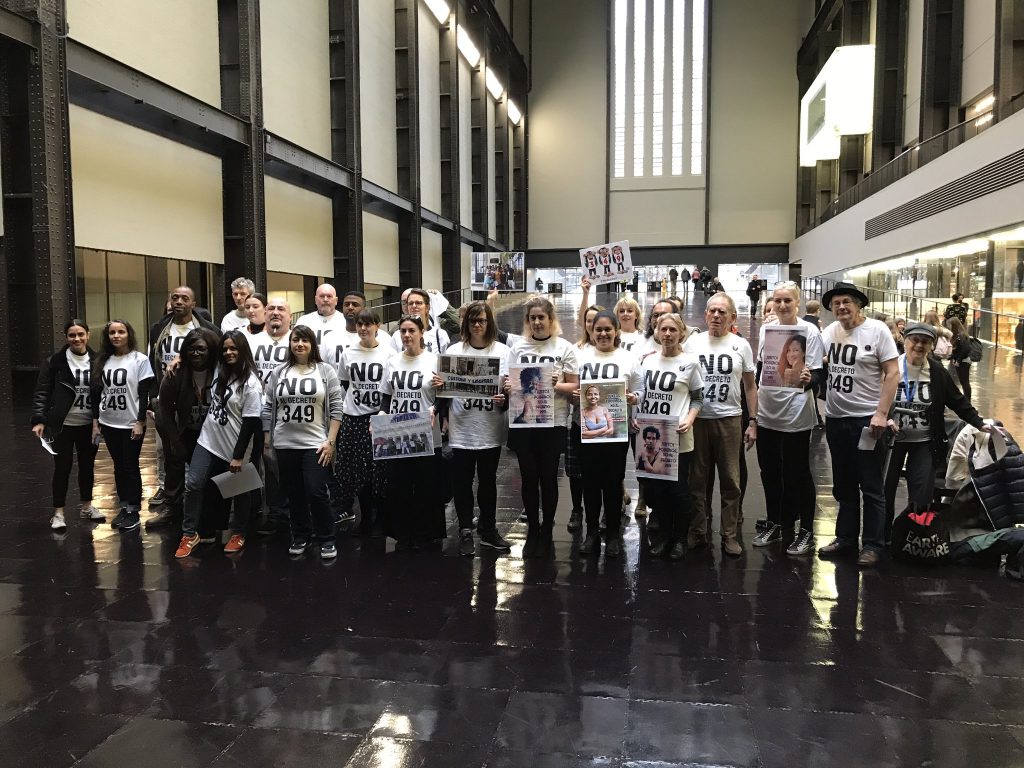

For their role in peacefully protesting Decree 349, Otero Alcantara and Nuñez Leyva were among 13 artists arrested, including Cuban performance artist Tania Bruguera, in Havana on 3 December 2018. Index joined others at the Tate Modern in London on 5 December in a show of solidarity with those jailed.

Protest in support of jailed Cuban artists at the Tate Modern gallery, London, October 2018.

On Human Rights Day on 10 December 2017, US Assistant Secretary of State Kimberly Breier tweeted: “[O]ur minds turn to the people of #Cuba, who have endured decades of repression and abuse at the regime’s hands, most recently via the creativity-crushing #Decree349.”

“The international help is positive because it makes visible the abuses of the Cuban regime against the people, but I think we must sacrifice ourselves in body and spirit — in a peaceful way — if we want to achieve our freedom,” Nuñez Leyva tells Index on Censorship. “We are very grateful for any help and pronouncements against 349. The redaction of the decree and the silence of the authorities is demonstrating that in Cuba there is a dictatorial regime in which no type of political, economic or social opening is taking place.”

In the days following all arrested artists were released, although they remained under police surveillance. Cuba’s vice minister of culture Fernando Rojas at the time told the Associated Press that changes would be made to Decree 349 but failed to open a dialogue with the artists involved in the campaign against the decree. A version of the law came into force on 7 December.

“We are determined to continue demanding the full repeal of 349,” Nuñez Leyva says. “We do not want to continue living in this perennial state of vulnerability.”

The persecution of the Museum of Dissidence isn’t limited to arrests. On 9 November Otero Alcántara took to Facebook to call out a campaign to discredit him. State security had been sending texts and holding meetings with his neighbours in what the artist said was a “desperate attempt” to “sabotage our activities”.

“The rhetoric that the government uses is well known to all — that we are mercenaries — and although most people no longer believe it, some of them decide to exclude you because you are a ‘marked’ person like you have a contagious disease,” Otero Alcántara tells Index. “You are a socially excluded and politically persecuted.”

“We try all the time not to give it too much importance, we try to smile because we really do not want to feel any bad energy,” he adds. “Our principle is love, dialogue, peaceful struggle. If they wish to defame us, it is on their conscience, not ours.”

Cuban artists Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara and Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, members of the Index-award winning Museum of Dissidence

Nuñez Leyva describes the efforts to dissuade Cuban artists from protesting 349 — including the seizure of anti-349 t-shirts emblazoned with three wise monkeys when re-entering Cuba after attending the Creative Time Summit in Miami — as “a mechanism to prevent the spread of the truth and above all, to make us tired and to resort to leaving the country”. But the Museum of Dissidence will not be deterred. “To achieve that, they will have to be more vicious.”

“The government spends innumerable resources to repress any type of expression that makes it uncomfortable,” Otero Alcántara says. “It seeks to discredit activists and artists all the time by isolating them from society, from their friends, from their family.”

After a seven-month campaign to attain visas to enter the UK — which saw the Museum of Dissidence denied visas on three occasions, causing them to them miss the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards ceremony in April 2018 — Nuñez Leyva and Otero Alcántara were finally able to receive their award at Metal Culture, an arts centre in Chalkwell Hall, Southend-on-Sea, on 18 October 2018. The artists were in residence at Metal for two weeks in October as part of their partnership with Index on Censorship.

“Southend-on-Sea generously gave us all its warmth. Staff at Metal, the uncharacteristically warm climate, the brick architecture of the place, the low tide river, the local legends told by a science fiction writer, the banks that paid homage to the deceased, the interest of the local media in the Cuban cause were encouraging for us,” Nuñez Leyva says. “To realise that a calm, inclusive city is possible opens us up and make us less naive when going back to face the Cuban reality.”

Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara as Miss Bienal

During his time in the UK, Otero Alcántara performed in Trafalgar Square on 26 October as Miss Bienal, a character he created in 2016 to symbolise the mulatto woman typified in clichés by tourist and for artistic consumption.

“Entering the National Gallery in a rumba dress without censorship made us realise the context of freedom and acceptance of difference that is breathed in London,” he says. “London is a giant city with so much art, diversity and history, it makes the body detoxify a bit from the bad energy you get living in a system like the Cuban one.”

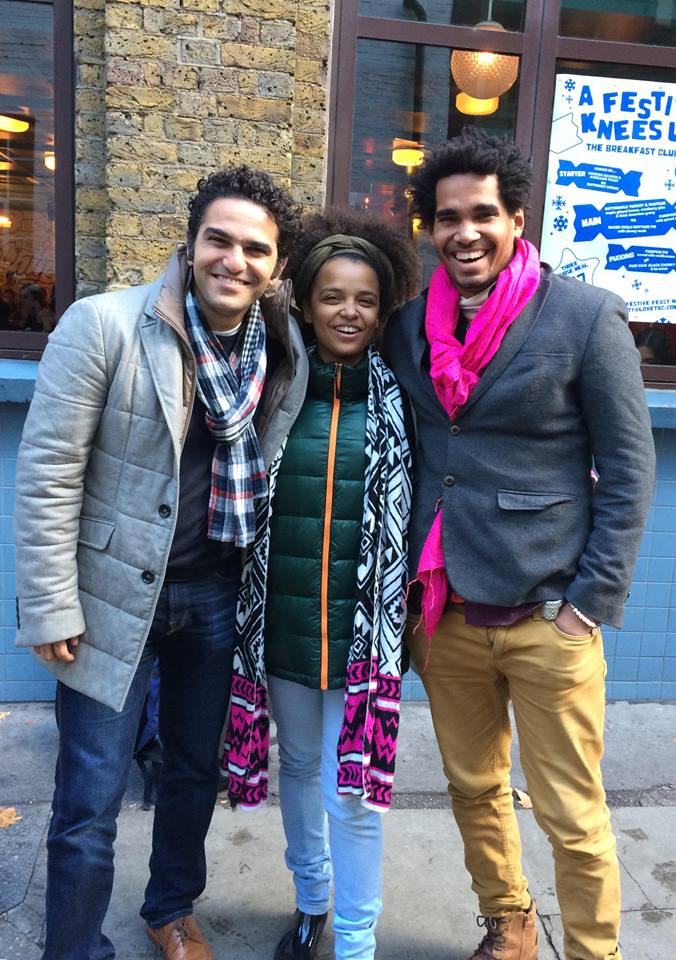

Mohamed Sameh with Yanelys Nuñez Leyva and Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara in London

While in London, the pair met with Mohamed Sameh, co-founder and international relations advisor at the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms, winner of the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for Campaigning. ECRF is one of the few remaining human rights organisations in Egypt, a country that often uses its struggle against terrorism as a justification for its crackdown on human rights.

“We shared with Mohamed the desire for prosperity in our respective countries, but also the smile that we shared, which we hold on to all the time,” Nuñez Leyva says. “The contagious smile of Mohamed is similar to that of, not only of the Museum of Dissidence in Cuba, but also Amaury Pacheco, Iris Ruiz, Coco Fusco, Student without Seed, Michel Matos, Aminta D’Cardenas, La Alianza, Yasser Castellanos, Veronica Vega, Javier Moreno, Tania Bruguera, and other artists who at this moment are fully engaged in the improvement of Cuba.”

“Although our contexts are different, we feel a total empathy with the struggles of Mohamed, because in our work we put ourselves at risk all the time for our rights and total freedom of expression, principles that for Mohamed are also non-negotiable.” [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1547483905239-0a56285c-5eb0-10″ taxonomies=”23707″][/vc_column][/vc_row]