Why has the issue of Gill’s abuse not been addressed by the museum before?

The issue has always been something that has been addressed, but always privately and 1-1. This is the result of almost two years of discussing how a more consistent and open conversation with our audiences might look.

Why does the museum feel it is ethically okay to continue to promote and celebrate the work of a child abuser?

The Museum’s charitable mission is to share the contents of its collection for public benefit – for learning, inspiration and enjoyment. Eric Gill is central to the museum’s story and narrative and is internationally regarded for his contribution to art, craft and design. We do not think it appropriate, nor helpful, to censor his work and have instead taken the decision to have an open and honest conversation with our visitors rather than brush this story under the carpet or turn a blind eye.

What do Gill’s descendants think about this exhibition?

We are now three or four generations away from Eric Gill and so it is invariably a big family, and like any large group their views vary hugely. We have had long, difficult but open conversations with many descendants and they are supportive of our decision to do the exhibition, and looking forward to seeing the extraordinary sculptures and drawings which we have brought together for the exhibition.

What do the inhabitants of the village think about this exhibition?

I think that when Fiona McCarthy’s book was published the village was surprised by the revelations, and I am sure it was discussed at length in houses and pubs across the village. Now nearly 30 years later I am sure that there will be no revelations in the exhibition rather it is an opportunity to really examine the question we always come back to: how much can we separate the artist from the work that they produce.

Why do you feel it’s necessary for people to know about Gill’s past? Why can’t audiences just enjoy his art?

We do hope that there will be works of art on display which audiences can enjoy, some of his most spectacular sculptures and drawings are included within the exhibition. However we do need to provide the information to our visitors that helps them to interpret and understand the works. I am sure that some visitors will object to us raising the biography again, the same as I know that some visitors will object to us failing to publicly acknowledge the abuse.

How do you think it will make museum visitors who have been subjected to sexual abuse feel?

From working with Brighton Survivors Network, National Association fort the Protection of Abused Children and Stop it Now, we are told that 1 in 4 women have experienced some sort of sexual abuse. Our interpretation is sensitive to this, and our publicity material is all clear about the content of the exhibition so visitors will be aware of what they are coming to see. All visitors will be signposted to authorities who will be able to help those who need to talk further, and we are grateful to these charities for their support and advice.

What measures do you have in place to help any visitors affected by the exhibition?

Referral information will be provided to all visitors with their tickets, as well as posters within the building. Staff and volunteers have received training from NAPAC and Wellcome Collection.

How can you sell a commercial show on the back of such an awful subject?

The museum is a registered charity and makes no profit from the exhibition; admission ticket income supports the ongoing costs of running the museum. Our primary objective is educational and this exhibition is part of our educational remit to interpret our collection and tell the stories associated with the artists in our collection and integral to our narrative.

How do you think this exhibition will affect families with children coming to visit the museum, especially over the summer holiday months?

The majority of the exhibition is appropriate to audiences of all ages, as is our permanent collection which occupies the majority of the museum. Across the 80 works on show we have four works which contain sexually explicit material. This will be clearly signposted in an age restricted area of the exhibition. We will be providing plenty of appropriate material for children and families within and beyond the museum walls during the exhibition.

What if visitors come to your museum just expecting to see some nice art (or not knowing what to expect) and are faced with this difficult subject?

The exhibition is being well promoted and all marketing material explains the narrative of the exhibition. The quality of the works on display is exceptional as is the permanent collection which is always the centerpiece of the museum’s displays. Museums are places to learn, discover and think … as well as enjoy. This exhibition will certainly inspire thought and discussion, but there is plenty of beauty

What do you say to those who believe that Gill’s public works should be removed?

We have a duty to preserve and maintain our collection, and to interpret it for our visitors. I don’t think that removing and censoring Gill’s work serves anyone, and the victim/survivor organisations which the museum is working with share the belief that opening up the conversation increases the likelihood of preventing and stopping abuse.

Ditchling is a quaint, rural museum celebrating a man who committed monstrous acts – how can visitors enjoy your museum and its exhibits in full knowledge of this history?

Not all art is to be enjoyed; some art is powerful for other reasons. Many people still do enjoy Gill’s work as wonderful examples of many craft forms. We also have many other artist’s work within our permanent collection and temporary exhibition programme. If visitors choose not to visit Eric Gill: The Body then I hope they will enjoy one of our future displays.

Why are Petra, Betty and Joan not represented in the museum?

We have work in our permanent collection by or of all four of Gill’s children and are actively collecting their work. We are particularly interested in their childhood drawings produced in the village and how these relate to their father’s work. Petra’s work as a weaver is also represented in our collection.

Did other members of the Guild and Ditchling community know about the abuse?

Although it was probably very clear to many people that Eric Gill was interested in sex and the body, this is very different from knowledge of any sexual abuse of his children. There is no evidence that anyone knew of this which would not be uncommon with interfamilial sexual abuse which relies on absolute secrecy.

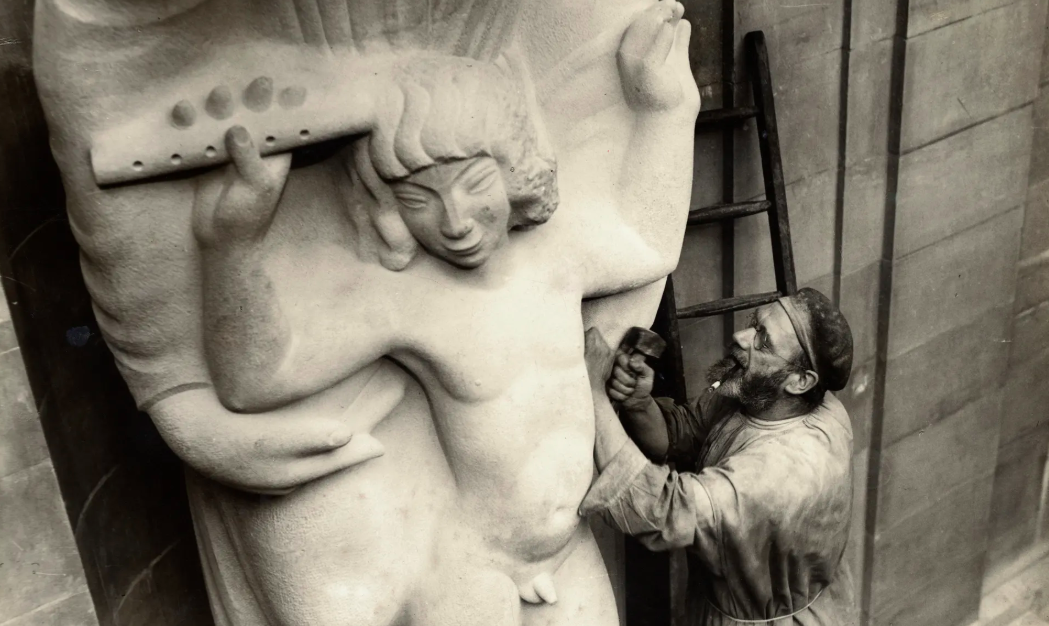

Is Gill a significant enough artist to celebrate anyway?

Gill is unquestionably an important artist who had a significant impact on carving, lettercutting, typography and wood engraving. His work is held in the permanent collections of museums across the world including Tate, V&A and British Museum in London. The typeface he designed is one of the most commonly used in the Western world and his sculptures grace the buildings of the BBC, Westminster Cathedral and the United Nations. Whether or not his work is celebrated is a more personal one and is integral to the question that we are asking our audiences.

How will the museum talk about Gill and display his work after this exhibition? Where does it leave the museum/what’s the legacy?

After this exhibition, and the learning that we have undertaken as a result, we will reflect on how the permanent collection displays can incorporate this information so that the museum does not turn a blind eye to Gill’s more disturbing biography again. This will more than likely take the form of including within our revolving permanent collection displays works by Eric Gill where knowledge if Gill’s abuse is critical to understanding the work. We will then provide this information in the correct context without sensationalizing.

Is the abuse continued/perpetuated by showing these works?

We have consulted with the Brighton Survivors’ Network, NAPAC and other charities who work with people who have been abused and we all believe that to stop future abuse it is better to talk openly rather than turn a blind eye and censor. We can well understand that for some these works are particularly hard to enjoy and appreciate. This is an issue explored in more depth within the exhibition.

Why show images of naked women who have been abused by their artist father?

These images are significant works of art and are part of our permanent collection which we have a duty to preserve, display and interpret. We have taken significant steps to present them in an open and honest way for people to make their own minds up as to whether the knowledge of the abuse affects our appreciation and enjoyment of the works of art.

Why is Petra the focus of the exhibition and not Betty?

Images of Petra and Elizabeth are included in the exhibition. Eric Gill made the carved wooden doll for Petra, and gave it to the museum, it is this object which particularly caught the attention of Cathie Pilkington and the inspiration for her new work Doll for Petra.

Aren’t you really drawing attention to Gill’s appalling private life in order to attract additional publicity and visitor numbers?

Fiona McCarthy’s biography on Gill was published nearly 30 years ago so the information has been in the public domain since then. Since the museum became dedicated to the art and craft of the village in 2014 the need to confront this central issue of whether we can separate the art and life of the artist has become more important. The Museum has spent two years consulting on the development of this exhibition and we believe it is our public duty to talk about the subject openly and honestly. It is not without financial or reputational risk for a museum to embark on a controversial subject such as this so is not programmed lightly.

Have you timed this exhibition now as ‘historic sex abuse’ is such a hot topic?

We have been working for the last few years to develop a way of talking more publicly about the issue within the museum, although superficially it may be easy to link Eric Gill to Rolf Harris or Jimmy Saville, in fact his was the harder to confront issue of interfamilial abuse which rarely goes detected or reported.

What warnings are you giving to alert visitors that some of the exhibits and what you call the ‘narrative’ may be disturbing or offensive, if they are?

All visitors will be given a leaflet with their tickets explaining the content of the exhibition, it will include a warning of sexually explicit material. This material will be in a separate area with additional age barriers.

Are all your Trustees comfortable with this exhibition and the approach you are adopting?

The museum’s staff and trustees have all been part of the process of developing this exhibition.

What about Dame Vera Lynn – does she even know the exhibition is taking place? Not her sort of thing, surely?

Dame Vera Lynn has just celebrated her 100th birthday and we were delighted to congratulate her on this. Understandably she is little involved with the day to day operations of the museum now but we are very grateful for her support in the past and her ongoing Patronage of the museum.

How does the wider artistic community in the UK see Gill in the light of the comparatively recent disclosures about his past?

I am sure that artists, like our wider visitors and audience, will take differing views on this issue. It is for this reason that the exhibition is framed as a question to ask how much our knowledge of Gill’s abuse affects our enjoyment and appreciation of the work he produced.

Do you regard Fiona McCarthy’s biography as authoritative? Has she been approached to attend and/or comment?

Other books have been published on Gill since Fiona’s biography but none question her discoveries. Our director is often in contact with her but, nearly 30 years after her biography on Gill, she is understandably working on new projects now.

Have you had any formal or informal; protests from feminist and/or victim support groups?

We have been working closely with Brighton Survivors Network, NAPAC and Stop it Now in preparation for this exhibition.

Has any of Gill’s work been removed from places where it was previously exhibited now that awareness of and attitudes towards incest and child abuse have changed?

We don’t know of any examples of Gill’s work being removed and his reputation as an extraordinary craftsman and designer continues to this day.

Do you believe that sexual behavior now regarded as abhorrent was much more over-looked or even accepted – particularly amongst artists – in the 1920s?

There is no evidence that anyone knew of Gill’s sexual abuse during his life. We think that Gill’s sexual abuse of his daughters was unacceptable – then or now.

What value is placed on Gill’s work commercially in the art market today? Does knowledge of an artist’s proclivities increase or decrease the value of their work?

There are many factors which influence the art market and as a public museum more concerned with artistic rather than monetary value, this is not an area in which we have expertise. Certainly Gill continues to be popular and prices have rised, but the cause of this is probably much more complex than the revelations in a biography almost 30 years ago.

What percentage of the permanent collection at Ditchling is by Gill?

We hold a large collection of Gill’s work in the museum’s permanent collection, but we also hold a large body of work by other great artists including David Jones, Frank Brangwyn, Ethel Mairet, Edward Johnston and others.

Do you think there is a risk once awareness of the exhibition builds your visitors to Ditchling may include voyeuristic abusers and paedophiles?

I think this is highly unlikely. The museum is a treat of a destination for any lover of art and craft across a broad range of crafts from silversmithing to weaving and natural dyeing. The work we are showing are extraordinary carvings, drawings and wood-engravings; this is not a sleazy voyeuristic exhibition but a thoughtful and considered analysis of Gill’s artistic output.

Gill was supposedly Catholic. Has there been any reaction to your exhibition from the Catholic Church?

We have not been working with the church on this exhibition. Although Gill was Catholic, and a founding member of the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic, the sexual abuse which he perpetrated was unconnected to the church and was interfamilial abuse between a father and his teenage daughter.

It is said Leonardo da Vinci abused the young students in his care – has anyone suggested his work should not be seen on this basis?

Our art historical expertise is probably too niche to be able to make comment on this. As far as we know da Vinci never visited Ditchling.

Will you be devoting any of your profits from this exhibition to any charities working with the victims of abuse? If not, don’t you think you should?

As a register charity we do not collect money on behalf of other charities but we are working closely with charities who work with people who have been abused. We hope that these will be long-lasting relationships with these charities and we would be more than happy to help them in their fundraising.

Aren’t some of Gill’s work simply frightening and upsetting? Shouldn’t your exhibits be uplifting and joyous?

The works on display are not frightening but the stories behind them might well be upsetting it is for this reason that we think correctly interpreting the works is necessary. Not all art is to be enjoyed; some art is powerful for other reasons. Many people still do enjoy Gill’s work as wonderful examples of many craft forms and that many of Gill’s depictions of the body are very beautiful and uplifting.

How do the women on the staff of the Museum feel about this exhibition? The Women’s Views on News website talks about ‘moral blindness’ surrounding Gill’s work today?

The staff team have worked closely together on developing this exhibition, and have absolutely not been morally blind in developing this exhibition. With any one member of the team, on any one day, I am sure we all feel different about Gill and particular works. This is why it felt appropriate to curate an exhibition such as this so that each work displayed is approached with the same question in mind: is the biography affecting my enjoyment and appreciation of the work. Sometimes the answer may be yes, at other times, it may be no.

Isn’t it true that Gill’s daughters did not regard themselves as ‘abused’? They are reported as having normal happy and fulfilled lives and Petra at almost 90 commented that she wasn’t embarrassed by revelations about her family life and that they just ‘took it for granted’. Aren’t we all perhaps making more of this than the people affected?

Elizabeth was no longer alive when Fiona McCarthy’s book was published, and those who met Petra certainly record a calm woman who managed to come to terms with her past abuse, and still greatly admired her father as an artist. I don’t think that we should try to imagine her process to reaching this acceptance as we know too little about her own experiences.

If you had bought a picture by Rolf Harris before revelations about his behavior came out, would you keep it or sell it?

We hope the exhibition will generate debate around these kinds of questions. I personally am not that familiar with Rolf Harris’s work as an artist so I am afraid I couldn’t comment further.