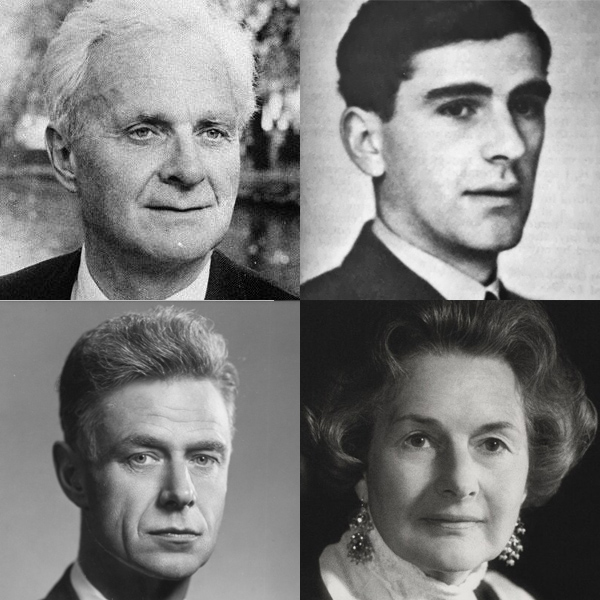

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116444″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Philosopher Stuart Hampshire knew evil was real. He had seen it, written about it and, perhaps, it had driven him to do something about it.

He was 25 by the time the Second World War broke out and he spent his formative years in a position in military intelligence.

His job was to interrogate, and it was this that brought him face to face with Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the high-ranking Austrian SS officer who was a key figure in the Holocaust.

Nancy Cartwright, Hampshire’s second wife and fellow philosopher, told Index, “He interviewed, as a young man, Ernst Kaltenbrunner. I think that had a real effect.”

Cartwright suggested that much of Stuart Hampshire’s personality reflected the work he was passionate about and he surrounded himself with revered thinkers and writers, including his closest friend, the political theorist Isaiah Berlin.

He was well-liked by his peers and was deemed to be warm-hearted and polite. Or, as Cartwright fondly describes him, “terribly English”.

As Cartwright remembered, he would sometimes sit in restaurants with Nancy and their two daughters and make up stories about the people sitting next to them, imagining who they were and what they were about in detail.

Stories, clearly, were important to him and people and the challenges they faced were significant too.

“I think he had a vivid sense of what it was like to be someone else. He could think of himself as being someone else,” said Emma Rothschild, the economic historian and Hampshire’s goddaughter – although this was never formalised at a font.

Hampshire was seen as a “cautious, honest and meticulous thinker” according to the philosopher Jane O’Grady, writing his obituary in The Guardian.

Free speech ranked highly among his values.

Cartwright said: “He had a sense that there is real evil and it needs to be combated. I think that was relevant to his work on Index. He was as much concerned about the people being censored and what was happening to them as he was about the issue in general.”

Hampshire, author of the acclaimed book Thought and Action, was a keen supporter of the post-war Labour government but never referred to it as such, instead preferring to say “the good Mr Attlee”.

“He always was distressed at inequality and poverty,” said Cartwright and he welcomed the wealth of social changes that Attlee oversaw: the foundation of the National Health Service and the expansion of the welfare state.

Hampshire also played a role in the implementation of the Marshall Plan, the financial rebuilding of Europe after the Second World War.

After the war, he became a senior research fellow at New College, Oxford before taking a domestic bursarship at his alma mater of All Souls. He later joined Princeton in its Department of Philosophy.

By the time the idea for the Writers and Scholars Education Trust, and Index, was being discussed, he had returned to Oxford as warden of Wadham College. Backing the idea of the trust and Index was natural to him.

“He was so keen on Index and it doing important things,” said Cartwright.

Emma Rothschild said his character was well-suited to setting up a free speech magazine.

“He was extremely involved with and excited about starting Index and I remember vividly seeing the first issues. It was one of his important steps into public life. He had been very involved in the great world of politics and international relations during and after the Second World War and then had been a bit more remote from it,” she said.

“I think Index was his way of moving back into large public questions. It was something he was extremely excited about and at the same time he found thinking about public life very stimulating for his philosophical writing.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]