The following article was first published by +972 Magazine, an independent, online, nonprofit magazine run by a group of Palestinian and Israeli journalists. Index on Censorship has reported on media freedom on both sides of the conflict since the 7 October attacks.

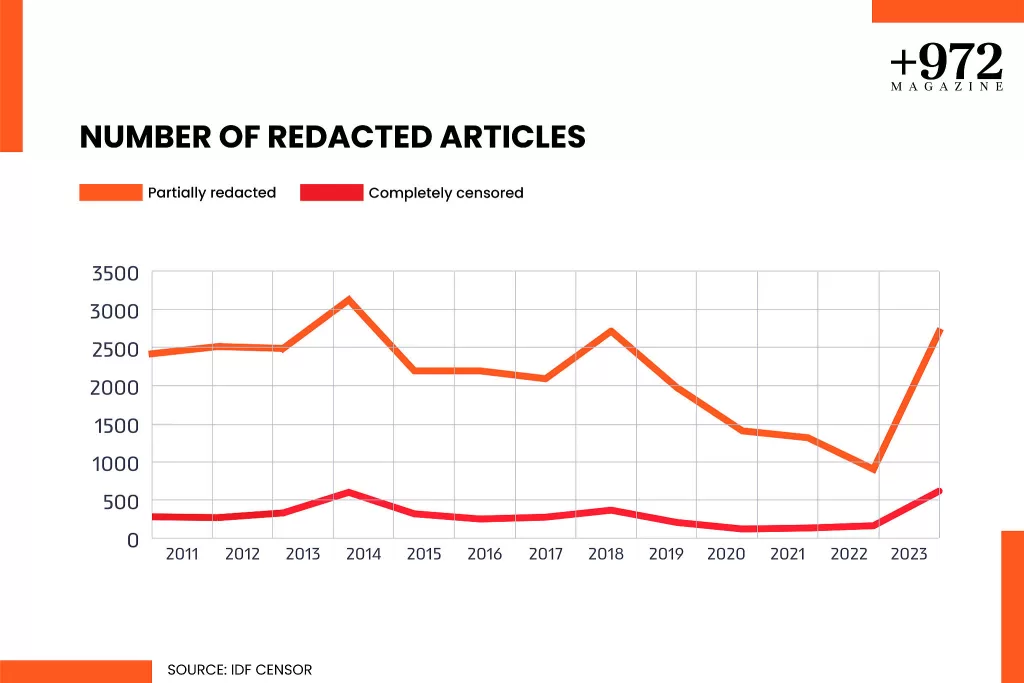

In 2023, the Israeli military censor barred the publication of 613 articles by media outlets in Israel, setting a new record for the period since +972 Magazine began collecting data in 2011. The censor also redacted parts of a further 2,703 articles, representing the highest figure since 2014. In all, the military prevented information from being made public an average of nine times a day.

This censorship data was provided by the military censor in response to a freedom of information request submitted by +972 Magazine and the Movement for Freedom of Information in Israel.

Israeli law requires all journalists working inside Israel or for an Israeli publication to submit any article dealing with “security issues” to the military censor for review prior to publication, in line with the “emergency regulations” enacted following Israel’s founding, and which remain in place. These regulations allow the censor to fully or partially redact articles submitted to it, as well as those already published without its review. No other self-proclaimed “Western democracy” operates a similar institution.

To prevent arbitrary or political interference, the High Court ruled in 1989 that the censor is only permitted to intervene when there is a “near certainty that real damage will be caused to the security of the state” by an article’s publication. Nonetheless, the censor’s definition of “security issues” is very broad, detailed across six densely-filled pages of sub-topics concerning the army, intelligence agencies, arms deals, administrative detainees, aspects of Israel’s foreign affairs, and more. Early on in the war, the censor distributed more specific guidance regarding which kinds of news items must be submitted for review before publication, as revealed by The Intercept.

Submissions to the censor are made at the discretion of a publication’s editors, and media outlets are prohibited from revealing the censor’s interference — by marking where an article has been redacted, for instance — which leaves most of its activity in the shadows. The censor has the authority to indict journalists and fine, suspend, shut down, or even file criminal charges against media organizations. There are no known cases of such activity in recent years, however, and our request to the censor to specify its indictments filed in the past year was not answered.

For more background on the Israeli military censor and +972’s stance toward it, you can read the letter we published to our readers in 2016.

“Information pertaining to censorship is of particularly high importance, especially in times of emergency,” attorney Or Sadan of the Movement for Freedom of Information told +972. “During the war, we have [witnessed] the large gaps between Israeli and international media outlets, as well as between the traditional media and social media. Although it is obvious that there is information that cannot be disclosed to the public in times of emergency, it is appropriate for the public to be aware of the scope of information hidden from it.

“The significance of such censorship is clear: there is a great deal of information that journalists have seen fit to publish, recognizing its importance to the public, that the censor chose not to allow,” Sadan continued. “We hope and believe that the exposure of these numbers, year after year, will create some deterrence against the unchecked use of this tool.”

A wartime trend

Although the censor refused our request to provide a breakdown of its censorship figures by month, media outlet, and grounds for interference, it is clear that the reason for last year’s spike is the Hamas-led October 7 attack and the ensuing Israeli bombardment of Gaza. The only year for which there was a comparable level of silencing was 2014, when Israel launched what was then its largest assault on the Strip; that year, the censor intervened in more articles (3,122) but disqualified slightly fewer (597) than in 2023.

Last year, the censor’s representatives also made in-person visits to news studios, as has previously occurred during periods in which the government has declared a state of emergency, and continued monitoring the media and social networks for censorship violations. The censor declined to detail the extent of its involvement in television production and the number of retroactive interventions it made in regard to previously published news articles.

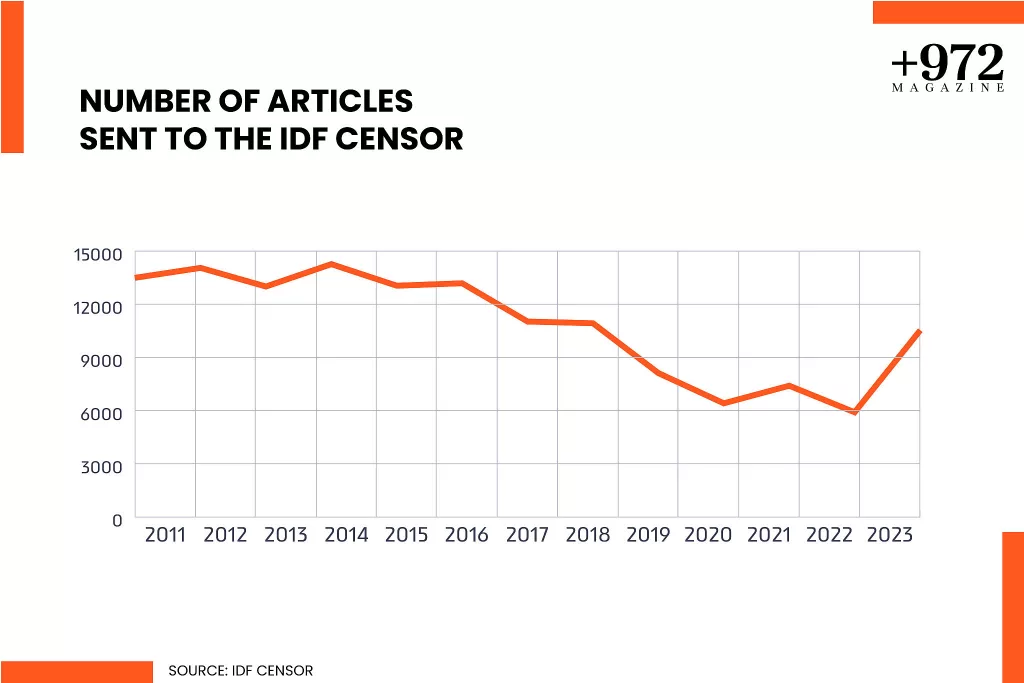

We do know, however, thanks to information revealed by The Seventh Eye, that despite the Israeli media’s proactive compliance — the number of submissions to the censor nearly doubled last year to 10,527 — the censor identified an additional 3,415 news items containing information that should have been submitted for review, and 414 that were published in violation of its orders.

Even before the war, the Israeli government had advanced a series of measures to undermine media independence. This led to Israel dropping 11 places in the 2023 annual World Press Freedom Index, followed by an additional four places in 2024 (it now sits in 101st place out of 180).

Since October, press freedom in Israel has further deteriorated, and the censor has found itself in the crosshairs of political battles. According to reports by Israel’s public broadcaster, Kan, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu pushed for a new law that would force the censor to ban news items more widely, and even suggested that journalists who publish reports on the security cabinet without the approval of the censor should be arrested. The chief military censor, Major General Kobi Mandelblit, also claimed that Netanyahu had pressured him to expand media censorship, even in cases that lacked any security justification.

In other cases, the Israeli government’s crackdown on media has skirted the censor and its activities entirely. Back in November, Communications Minister Shlomo Karhi banned Al-Mayadeen from being broadcast on Israeli TV, and in April, the Knesset passed a law to ban the activities of foreign media outlets at the recommendation of security agencies. The government implemented the law earlier this month when the cabinet unanimously voted to shut down Al Jazeera in Israel, and the ban will now reportedly also be extended to the West Bank. The state claims that the Qatari channel poses a danger to state security and collaborates with Hamas, which the channel rejects.

The decision will not affect Al Jazeera’s operations outside of Israel, nor will it prevent interviews with Israelis via Zoom (full disclosure: this writer sometimes interviews with Al Jazeera via Zoom), and Israelis can still access the channel via VPN and satellite dishes. But Al Jazeera journalists will no longer be able to report from inside Israel, which will reduce the channel’s ability to highlight Israeli voices in its coverage.

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel and Al Jazeera petitioned the High Court against the decision, and the Journalists’ Union also issued a statement against the government’s decision (full disclosure: this writer is a member of the union’s board).

Despite these various attacks on the media, the most significant threats posed by the Israeli government and military, and especially during the war, are those faced by Palestinians journalists. Figures for the number of Palestinian journalists in Gaza killed by Israeli attacks since October 7 range from 100 (according to the Committee for the Protection of Journalists) to more than 130 (according to the Palestinian Journalists Syndicate). Four Israeli journalists were killed in the October 7 attacks.

The heightened government interference in Israeli media does not absolve the mainstream press of its failure to report on the army’s campaign of destruction in Gaza. The military censor does not prevent Israeli publications from describing the war’s consequences for Palestinian civilians in Gaza, or from featuring the work of Palestinian reporters inside the Strip. The choice to deny the Israeli public the images, voices, and stories of hundreds of thousands of bereaved families, orphans, wounded, homeless, and starving people is one that Israeli journalists make themselves.

This article was previously published by +972 here.