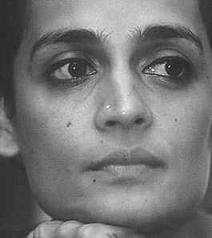

Arundhati Roy has been accused of sedition after claiming Kashmir was not part of India. Her comments may be controversial, but the real scandal is the law, says Salil Tripathi

“Kashmir has never been an integral part of India. It is a historical fact. Even the Indian Government has accepted this.”

These words may exasperate an Indian nationalist, but they are hardly unusual, and if they are considered inflammatory and capable of inciting hatred, then something is indeed rotten in the state of India.

And yet, Arundhati Roy, who won the Booker Prize for her novel, “God of Small Things” in 1997 and who has since become an outspoken critic of the Indian state, now faces a possible prosecution under India’s sedition laws for saying just that at a seminar in New Delhi on October 21.

If sentiments expressed on the Internet — through Twitter and Facebook — are an indicator, her remarks have outraged many Indians. Some want her to be sent away to jail for a long time. One even tweeted that she should face capital punishment, although the maximum punishment under the sedition law is life imprisonment. For its part, the government has not said it will prosecute Roy, although a lawmaker of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party from the northern state of Uttarkhand has filed an official complaint, which could set the stage for some legal action.

That is outrageous. To be sure, Roy is not popular among Indian politicians and with the country’s burgeoning middle class. She is an ardent and fervent critic of the Indian state, which, as per her worldview, can do nothing right. She has spoken out against India’s nuclear policy, has condemned economic liberalisation, decried the treatment of people displaced by the construction of major dams, championed the cause of indigenous people who have been fighting large corporations making incursions into lands that they consider theirs, and cheered on the Maoists, who claim to represent India’s poor, underprivileged underclass.

Initially her dissent was seen as admirable, then as a novelty, and now her view is largely marginalized. She may even have more fans at liberal campuses in the West and among the readers of the Guardian (which faithfully co-publishes her long essays that also appear in Outlook magazine in India, while marginally editing them for a western audience) than in India. But her popularity is irrelevant. What’s relevant is the kind of democracy India is, or wishes to be.

With all its flaws, India is a democracy, and a real democracy has room for dissent. Roy has her critics in India, and those critics are not cheerleaders of “neoliberal capitalistic imperialism”, but thoughtful development experts, historians, and even left-leaning academics. Many have joined issue with her, debating her positions on matters of substance.

That is how India deals with such disputes — through debate and argument, not threats of prosecution. India seems to want it both ways — it wants praise for being a democracy (which it is) but doesn’t want to be criticized when it turns on its own writers and intellectuals (which it does). As the writer Hari Kunzru said in a statement issued by the English PEN:

“India trumpets its status as the world’s largest democracy, but the Indian establishment is notoriously unwilling to listen to dissident voices. Whether or not one agrees with Roy’s positions on Kashmir or the Maoist insurgency in Central India, the issues she raises are important and deserve to be debated. The willingness by elements of the Indian establishment to use the legal system to intimidate critics is lamentable. India’s writers are an important part of the nation’s identity on the international stage. Supporting their right to free speech goes hand in hand with applauding them when they win the Booker prize. One is meaningless without the other.”

It is worth stressing that what Roy has said is not particularly controversial, nor necessarily new. The status of the province that India calls Jammu and Kashmir is a matter of an international dispute. As the state’s chief minister Omar Abdullah — grandson of the state’s most influential politician, the late Sheikh Abdullah — put it recently, at the time of Independence in 1947 Kashmir acceded to India, but did not merge with India. (The BJP condemned that statement and wanted action taken against him at that time). Abdullah’s statement – like Roy’s – is unremarkable, if less assertive than Roy’s. At the time of Independence in 1947, Kashmir’s Hindu ruler Raja Hari Singh did not decide immediately if he wanted his Muslim-majority province to be part of the Muslim state of Pakistan, or the secular state of India. While he dithered, Pakistan-supported tribesmen overran parts of Kashmir. The ruler sought Indian military assistance, which India was willing to provide, if Kashmir agreed to join India. An accession treaty was signed, with the condition that India would hold a plebiscite to formalise the accession, but such a plebiscite was never held. Indians said they could not hold such a plebiscite so long as Pakistan-backed tribesmen remained in the part of Kashmir they had overrun.

Over the past 60 years, India has held several elections in the state, and says those elections have made the plebiscite unnecessary, since Kashmiris have participated in those polls. But some of those elections have been rigged, violence has followed, and the Indian Government has frequently deployed troops or removed inconvenient regional leaders. Since the late 1980s, the mood has soured in the Valley, with more Kashmiris openly seeking azadi, or freedom. India has responded with force. Meanwhile, the legitimate freedom movement has been overshadowed by extremists from Pakistan and elsewhere, who have sought to impose a fundamentalist Islamic identity in a region traditionally inspired by the more liberal Sufi tradition of Islam. And those extremists are hardly pristine freedom fighters: they have terrorised the state’s Hindu population, known as Pandits, many of whom have been forced to leave Kashmir. In the dreadful violence of the past two decades, thousands have died, and there have been appalling instances of extremist violence on one hand (sometimes against women who don’t follow the dress code they’ve prescribed), and of torture and degrading treatment of young men the Indian army has arrested, on the other.

Roy is not the first writer to point out these problems. But her persistent critique of India, which does not acknowledge that other than western democracies, India is among very few countries where a dissident like her can express such contentious views freely, that riles her opponents. A leading Indian broadcaster tweeted on Oct 27: “hope she will finally appreciate the space this democracy gives her and find ONE good thing to say about India.” That is a common Indian lament, but it misses the point: freedom of speech is not a privilege India grants Roy; it is her right.

Writers shouldn’t be expected to toe a specific line; they are not meant to behave. The whole point of freedom of expression is that the right is not restricted even when the person exercising the right says things that are utterly unpalatable, offensive, and outrageous. Writers challenge the boundaries of what is acceptable; they challenge the status quo; they push; they make people see what they don’t want to see. The atrocities committed by the extremists are horrendous – but that doesn’t justify the way the Indian troops have acted.

And yet, it does not mean that whatever Roy says is necessarily right. She is often — some would say usually — wrong. Her valourisation of Maoists, for example, is reprehensible and irresponsible; in her poetic flourishes about the romantic, revolutionary lives the Maoists lead (which she wrote about in her embedded journalism), she did not mention that Maoists have used child soldiers, did not question their show trials which lead to execution of people they consider informers, and didn’t feel appalled that they placed roadside bombs, including sophisticated improvised explosive devices.

But she has the right to express her views. The biggest demonstration of India’s openness is that even a critic as unforgiving as Roy is not prosecuted. Using sedition laws — which the British used against Gandhi — against her is exceptionally myopic. Rather than prosecuting Roy, India should revoke the sedition law, which undermines its democratic credentials.