Why is South Korea’s blocking the website of a company that offers tours in the North? Robin Tudge reports

The website of a tourism company that takes guided tours into North Korea has been blocked in South Korea, becoming another victim to efforts by Seoul to quash all efforts promoting any kind of engagement with the North.

Koryo Tours is a Beijing-based tourism group run by Briton Nick Bonner that since 1993 has taken in thousands of visitors to North Korea. However, since January this year people in South Korea can access neither www.koryotours.com nor www.koryogroup.com as they purportedly contain content in breach of Article 7 of the National Security Law (NSL), as anyone who “praises, incites, propagates or cooperates with activities of an antigovernment organization… or who propagates or instigates a rebellion against the state” or threatened its security, with imprisonment threatened for any breaches.

Bonner called the move “a slap in the face” for a firm that has striven to work towards stability and understanding with the people of North Korea, in a state isolated state usually portrayed as Stalinist, starving and a threat to world peace. Koryo’s previous projects have involved arranging exchanges for sports teams and schools, works supported by both the British and South Korean governments, and Bonner has also co-produced three pioneering, award-winning documentary films about North Korea with the BBC, The Game of Their Lives, A State of Mind and Crossing the Line, that have been shown and celebrated in cinemas in both North and South Korea and the US. However, Bonner is sure his forthcoming film, a romantic comedy set in North Korea, will not be shown, “and with this current attitude our three films wouldn’t have been shown… There was clearly an interest in South Korea to find out more about life in the north, and I believe the less ignorant and better informed people are, the more the chance for moving forward.”

Koryo Tours is emphatically not some fellow traveller outfit, and as Bonner says, their website has “nothing in it that would make anyone go and live in North Korea, or to create chaos in South Korea”.

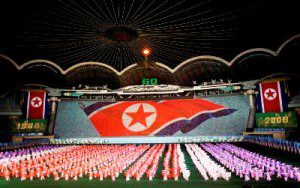

The blocking was carried out by South Korea’s National Intelligence Service, and while Bonner’s efforts to contact them proved fruitless, the British Embassy in Seoul brokered a meeting in May with the Korean Communications Standards Commission. However this proved to be a “one sided-affair”, as the commission demanded the removal of photos of North Korea’s famous hand-painted posters; then, pictures of any military objects, albeit North Korean military objects; then a picture of a smiling golfer, then North Korean opera posters, then a picture of the Mass Games that had an image of Kim Il Sung in the background. When they moved on to textual content, Bonner gave up.

One link Koryo Tours did remove was that to North Korea’s state news agency website, Korea Central News Agency, www.kcna.co.jp, better known for relating developments that may lead to South Korea or the US being drowned in a sea of fire. But only on August 5 KCNA reported a balanced story that noted that the South Korean authorities had described some of Koryo Tours site contents as ‘being for pro-DPRK propaganda purposes,’ while Koryo Tours called the blocking “unreasonable”.

“Any form of engagement with North korea is very difficult,” says Bonner, “but with South Korea for now, it’s absolutely zero. They want nothing to do with the North.” The NSL was first passed in 1948 and since been criticised for its restrictions on free speech by the US and UK governments and Amnesty International, but since the election of Lee Myung-back in 2007, its use to target any group suspected of supporting communism or alignment or sympathy with the North has resurged while the South-North rapprochement and engagement efforts of the 1990s and 2000s Sunshine policy have been ditched. Only on July 24 the NIS searched the offices of Minjog 21, a monthly publication that discusses North and South Korean current events, over suspicions that its executive editor, Ahn Young-min, traveled to Japan to receive orders from a North Korean agent.

South Korea’s press freedom ranking has fallen sharply in recent years, most recently slipping in the Freedom House 2011 Press Freedom Survey from “free” to “partly free”. OpenNet Initiative has concluded that while South Korea may be a world leader in Internet and broadband penetration, its citizens “do not have access to a free and unfiltered Internet”.

North Korea, unsurprisingly, was last in the 2011 survey, not least as all media is state owned and directed, while its population has no access to the worldwide web. However, there have been subtle shifts that, in a land where admittedly any sign of life is heavily-caveated news, may yet brook great significance.

In June 2010, Star Joint Venture, a Thai-North Korean company, bought a block of over 1,000 IP internet addresses with North Korea’s official domain name, .kp, to be run under the firm Dot-KP. A multi-language general information page about North Korea, www.naenara.com, undertook the .kp protocol, while in July 2010 a North Korea homepage, www.uriminzokkiri.com, joined Twitter and Facebook.

However, access is blocked in South Korea to at least 30 North Korean websites and more Twitter accounts, with South Korean visitors to these sites being redirected to the National Police Agency’s warning site. One site is uriminzokkiri.com’s Twitter feed, @uriminzok, which regales its near 11,000 followers with tweets like “Kim Jong Il Sends Autograph to Officials and Employees of Fruit Farm” — and which South Korea blocked in August 2010.

But how effectiveness is the North’s propaganda, when its own people are bored by it, according to reportage on www.northkoreatech.org. Most young people in major cities have seen South Korean TV dramas, smuggled in on pirate DVDs in a trade that even the police tolerate as they also like the shows. But as this dubiously tolerated undertow of engagement with South Korean culture goes on the North, any reciprocal Southern interest in Northern culture is officially verboten. And as Bonner says, that the South Koreans might “up and rebel” because of a tourism website is “a little bit sad”.

Robin Tudge is the author of the Bradt Guide to North Korea and the recent No Nonsense Guide to Global Surveillance