In post-revolution Egypt, street art has become one of the symbols of ongoing resistance. Yasmine El Rashidi reports on the graffiti artists of Cairo

In post-revolution Egypt, street art has become one of the symbols of ongoing resistance. Yasmine El Rashidi reports on the graffiti artists of Cairo

Ayman handed himself in at noon on 27 April 2009. The police had been searching for him for three days, and his name had made headlines in the local press. He was the criminal still at large – his two accomplices had already been caught. They were held in an unknown location, under investigation. We all knew they were being interrogated, maybe even tortured.

The phone call had come the night before. “We need your help. I’m not sure what to do. Nobody wants to touch this case. I need you on this one, can you go with him?”

Ayman was a friend and I had worked with him on projects in the past. Maybe the presence of a woman would lessen the brutality he might face.

The police seemed surprised when we showed up the following day. In Mubarak’s Egypt, the police and state security were known for their heinous torture methods and arbitrary detentions. Nobody voluntarily handed themselves in, and we weren’t sure what they would do. Ayman admitted he was sick from fear. That morning, his face was drawn and he was gnawing at his nails.

At the downtown police station — a decrepit villa that had long ago been seized from a family who was forced to flee — we were escorted up worn stairs to a pre-fab top floor. There, in a cramped, smoky room, we were left to wait. I was offered a chair, Ayman the floor. He chose to stand.

Over the hours as we waited, mid-ranking officers came to ask who we were, what our case was.

“I’m an artist,” Ayman would say. “I make art.”

“She helps me come up with ideas.”

We had rehearsed our narrative: I was the ideas person — the one who came up with the project. He just executed — made the art. We had prepared a paper — the “project proposal” to give our story legitimacy, to try to break down the project in a language the police could understand. Our document began (in Arabic): “Inspired by the rise of street art around the world, and the growing emphasis being placed globally on the artist as community activist, Cairo-based artist Ayman took to the streets of Cairo last month in an effort to use his art to contribute to the city.”

The officers trailed in over the course of four hours. Each asked a question or two before nodding their heads and leaving. They seemed ill-equipped to deal with our case, and eventually, we were told that we would have to wait for the top-ranking officer — the head of the police station –– to arrive. He didn’t come in to work before late afternoon, but we could go in there. They pointed to another room with a rusty iron bed and flattened sponge mattress.

“There’s a TV on,” an officer told us.

“Enjoy,” he added, as he walked out laughing at the screaming blaring from the TV –– a torture scene in an underground Egyptian jail. An Egyptian thriller and drama.

Mixed messages?

Ayman was formally detained later that night. Over 14 hours, we had been subjected to endless rounds of questioning by police, a trip to a nearby court, and three interrogations by high-ranking officers; they already seemed to know everything about us, but each quizzically took us in, unsure what to conclude.

Ayman was formally detained later that night. Over 14 hours, we had been subjected to endless rounds of questioning by police, a trip to a nearby court, and three interrogations by high-ranking officers; they already seemed to know everything about us, but each quizzically took us in, unsure what to conclude.

At 2am, they told me I could leave. Ayman, they said, would have to wait. He would spend the night in the police station jail. The charges were yet unknown. The police were unsure how to classify his act: what it meant, how great a danger he may be.

“It looks like it could be the eagle on the Egyptian flag with its wing broken,” we had heard one officer say in the hours as we waited. “Maybe that means, destroy the government.”

“It is a communist movement,” another offered.

“They want to overthrow the regime,” an informant said.

That night in the police station, Ayman stayed up, pacing. He was to be transferred to the state security headquarters early the following morning for further interrogation. At 7am the prison truck would arrive, the officer had told me before I left. “You can wait for him outside,” he said. “But we don’t know how long it will take. You might be there for days.”

In the next 48 hours, waiting for Ayman’s release, I learnt the police side of the story. They woke up one morning, one of them told me, and found five streets surrounding Tahrir Square filled with a “strange looking” figure painted on the walls. “It looked like it might have been a cult,” one officer told me. “Definitely a threat to the government.”

“One young officer ignored the first of these paintings, but then, the next morning, there were so many more of them. We couldn’t ignore it. We weren’t really sure what it was. The idea of writing on walls being art makes no sense to us.”

The graffiti on the streets downtown for which Ayman had been arrested depicted a street sweeper. A thin stencil outline of a man holding a broom. “Keep your city clean” was the thought behind his abstract art, “Love your country.”

One of them admitted: “None of the officers want to sign off on his case. No one is really sure how many followers he has and what this is really about. What does this symbol really mean? What is the message? We can’t take the risk. No one wants to lose their jobs.”

I met up with Ayman again on 28 June 2011, on a sidestreet near Tahrir Square, just minutes from where his street art had once been and around the corner from the state security headquarters where he had been blindfolded and interrogated. Clashes between protesters and riot police had begun late the night before, and by the morning, the street was the site of a pitched battle. Protestors chanted against the military, some of them threw rocks. The riot police responded with rounds of tear gas.

For hours this battle went on — the protesters moving forward, the police firing back. Young men and women were being carried out of the crowds, hit by tear-gas canisters or faint from the gas. A young boy went up in flames. There were informants in our midst, and soldiers in the distance, but the crowd relentlessly pushed on — not willing to yield.

During the 18 days of the Egyptian revolution, when the police were symbolically defeated and the army took control of the streets and the state, our fears of the notorious state security apparatus had been broken, and the streets of our cities had become, in many ways, our own.

“I feel I can do whatever I want now,” a friend had told me soon after Mubarak stepped down. “I want to spray the streets with paint.”

In the weeks that followed, my friend, other friends, artists, non-artists, took to the streets to do just that: fill the walls of the streets of Cairo with murals and art. “Freedom = Responsibility”, paintings of the martyrs, “VIVA EGYPT”, abstract collages of the Egyptian flag, pastiches of symbols of liberation. The self-censorship that we had all long subjected ourselves to was slowly lifting. The signs of it were everywhere.

Our fears had beenLast week, on that sidestreet of Tahrir, by a graffiti scrawl that said “F*** the Police”, Ayman and I talked about how things had changed.

“We’re free now,” he said as he snapped pictures on his phone. “We can do whatever we want.”

Taking back the streets

Some weeks ago, a friend and artist, MoFa, also known as Ganzeer, organised a “mad graffiti weekend” intended to “take back” the streets of the city. For many days he and a group of activists, artists, friends and volunteers gathered in his rooftop studio to discuss their plans.

Some weeks ago, a friend and artist, MoFa, also known as Ganzeer, organised a “mad graffiti weekend” intended to “take back” the streets of the city. For many days he and a group of activists, artists, friends and volunteers gathered in his rooftop studio to discuss their plans.

By the time they hit the streets mid-May, they had stencils ready, vast supplies of paint, walls identified, and friends to photograph and film them. Their graffiti largely mocked and criticised the ruling military council, which had risen to power since Mubarak stepped down on 11 February. It depicted the underwear of the ruling Field Marshall Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, “freedom masks”, or muzzles, that spoke of the reality of military rule, and murals of army helicopters and life-size tanks.

MoFa, along with some friends, made posters of one of the works — the Freedom Muzzle, criticising Field Marshall Tantawi. On 25 May, as they were plastering the poster downtown ahead of a big protest planned for that weekend, MoFa and two friends were detained –– to be released, quite swiftly, several hours later after straightforward questioning.

I received an email the next day when the news hit the local press.

“I’m sure you’ve seen this,” my friend Bruce –– an international critic, a dean at the American University in Cairo, and big supporter of street art — wrote, referencing a link to an article about the arrests.

I wrote back: “I do. But I’m not sure how much sympathy I have. Around the world street art is considered vandalism, so content aside, this should come as no surprise. When Ayman was arrested a few years ago, no one was willing to support him. Of course now all these guys are raging about how bad the army is. Yes, the army is problematic, but, in the military council’s mind, it’s these same youth who were burning the Israeli flag and threatening to storm the embassy last week. That was one of the most destructive acts to the legacy of this revolution — to its peaceful nature, to its spirit. Why not use street art to raise awareness, to subtly provoke thought, to reach out to the masses? Are direct political statements art? Is provoking animosity towards the army art?”

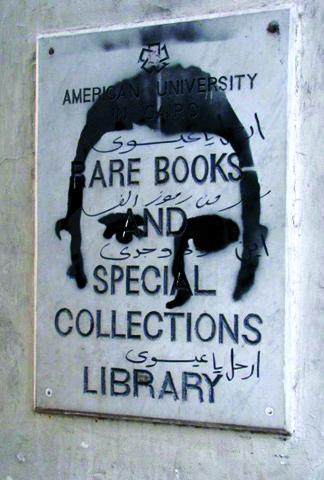

Some weeks later, on the one-year anniversary of the death of Khaled Said, the 28-year-old man who was beaten to death at the hands of police last year, activists and citizens at large took to the streets in his memory. Many of them held up pictures of him. Others hoisted the Egyptian flag. Some had stencils and cans of paint — portraits of Khaled that were plastered on downtown streets: on random buildings, on the walls of the Ministry of Interior, on shop windows and shutters. One of the portraits was sprayed over the marble plaque of the American University’s Rare Books and Special Collections Library, which stands a few blocks from Tahrir. A friend took a picture of it. I sent it to Bruce. “Art or vandalism?” I wrote in the subject line.

This article appears in the new edition of Index on Censorship. Click on The Art Issue for subscription options and more.

Yasmine El Rashidi is a writer based in Cairo. She is a frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books and the author of the Battle for Egypt: Dispatches from the Revolution (New York Review of Books)