The protests against controversial film “Innocence of the Muslims” follow a pattern familiar since the days of the Satanic Verses fatwa, says James Kirchick. And so do the reactions of many western liberals

Take Two: Film protests about much more than religion

The United States is the world’s undisputed king of culture. No country’s film industry can rival Hollywood; no nation’s musical artists sell more records worldwide than America’s. Boasting such a diverse, pulsating, frequently vulgar and often blasphemous entertainment industry, not everyone — including many Americans — is going to be pleased with what they see and hear coming out of the United States. Films ranging from Martin Scorcese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (which depicted the lustful fantasies of the Christian savior) to Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (which depicted Jesus’ crucifixion as essentially Jewish-orchestrated) have outraged Christians and Jews, respectively. The latest Broadway smash hit, The Book of Mormon, mercilessly ridicules the foundation myths of America’s newest and fastest-growing major faith.

In none of the controversies surrounding these productions, however, did the producers fear for their lives, nor did US government officials feel it incumbent upon themselves to apologise to the world’s Christians, Jews or Mormons for the renderings of artists. This straightforward policy of respecting the autonomy of the cultural sphere was amended earlier this week, however, when a branch of the United States government officially apologised to the world’s Muslims over a film for which the word “obscure” is too generous.

On 11 September, 12:11 PM Cairo time, the Embassy of the United States to Egypt released the following statement:

The Embassy of the United States in Cairo condemns the continuing efforts by misguided individuals to hurt the religious feelings of Muslims — as we condemn efforts to offend believers of all religions. Today, the 11th anniversary of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States, Americans are honoring our patriots and those who serve our nation as the fitting response to the enemies of democracy. Respect for religious beliefs is a cornerstone of American democracy. We firmly reject the actions by those who abuse the universal right of free speech to hurt the religious beliefs of others.

The “misguided individuals” in question were the producers of the now-infamous YouTube flick, The Innocence of Muslims, a crude, low-budget film which portrays the Prophet Muhammad in a none too pleasant light. Much about The Innocence of Muslims remains a mystery; its now-debunked origin story, that of an “Israeli Jew” filmmaker who “financed [it] with the help of more than 100 Jewish donors,” had all the makings of anti-Semitic disinformation campaign.

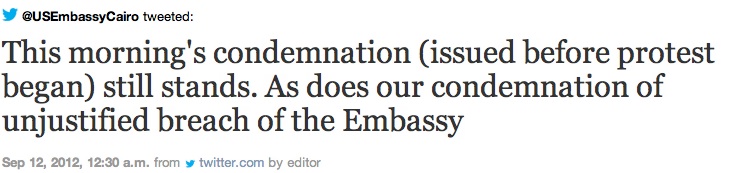

Several hours after this statement was released on the Embassy’s website, about 2000 Salafist protestors gathered outside the US Embassy, breached the compound’s walls, took down the American flag, and replaced it with the a black banner inscribed with the Islamic profession of faith: “There is no God but God and Muhammad is his prophet.” When, in the aftermath of this outrage, some American conservative bloggers began criticizing the Embassy’s statement as an apology for a specific exercise — however crude — of the constitutionally-protected right to free speech, the Cairo Embassy’s Twitter account defiantly released the following:

Shortly after 10:00 P.M. that evening, the campaign of Mitt Romney, Republican presidential nominee, released the following statement:

I’m outraged by the attacks on American diplomatic missions in Libya and Egypt and by the death of an American consulate worker in Benghazi. It’s disgraceful that the Obama Administration’s first response was not to condemn attacks on our diplomatic missions, but to sympathize with those who waged the attacks.

This riposte was embargoed until midnight, 11 September being a day that American politicians exempt from their usual partisan sniping. Yet, shortly after releasing the statement to the media, the Romney campaign lifted the embargo. Heightening the controversy was the revelation that Islamist militants had attacked the American consulate in Benghazi, Libya (it would not be confirmed until early next morning that the Ambassador, Chris Stevens, had been killed). Suddenly, an issue not normally considered American presidential campaign material — freedom of speech — had become a political football.

Since then, the liberal chattering classes, as well as ostensibly unbiased news reporters, have universally condemned Romney for “politicising” a national tragedy (just watch this press conference Wednesday morning in which reporter after reporter asks the Republican candidate, incredulously, how he could deign to stoop so low). The main line of attack against Romney is essentially a defense of the US Embassy’s original statement, which, in the words of Washington Post columnist Dana Milbank, “came out before the attacks, was issued by career diplomats in Cairo without clearance from Washington, and was disavowed by the White House.” This line was echoed in a New York Times news story, which reported that “The embassy’s statement was released in an effort to head off the violence, not after the attacks, as Mr. Romney’s statement implied.”

“But the fact is that the ‘apology’ to our ‘attackers’ was issued before the attack!” pronounced Michael Tomasky of The Daily Beast. Josh Marshall, proprietor of the popular Talking Points Memo blog, declared that the two-sentence statement from the Romney campaign was reason enough to disqualify the former Massachusetts Governor from the presidency. “Romney, or folks writing in his name at his campaign, claimed that the administration’s first response to the attacks was to issue a press release condemning the anti-Islam film which had helped trigger the attack,” Marshall wrote. “In fact, according to all available press reports and the account of the State Department, the press release in question came from the US Embassy in Egypt and preceded the attacks” (emphasis original).

The New York Times, America’s left-wing pundits, and the rest of those who have criticized the Romney campaign are missing the point, which is that it is no more appropriate to apologise for the First Amendment before a raging mob attacks an American embassy than it is to apologise for the First Amendment after such an attack occurs. The embassy’s pre-emptive apology – and that’s exactly what it was – shows just how useless it is to apologise for the most basic principle of the Enlightenment. Someone who would ransack an embassy and kill American diplomats over a movie he saw on the internet is not likely to be persuaded by a mere statement assuaging his “hurt religious feelings.”

The Obama administration did indeed repudiate the Embassy’s statement – which has since been removed from its website – and some sources have anonymously claimed that the release was the work of a freelancing, public diplomacy officer who acted without express approval from Washington. This, the administration’s supporters claim, absolves the president of blame for a statement they nonetheless defend on its merits. Regardless, the buck stops with the President of the United States; if a US Embassy releases a statement, one must assume it is something the President stands behind. Revoking the statement while failing to discipline or fire the individual behind it sends mixed signals. Moreover, in remarks at the White House condemning the murder of Ambassador Stevens, the President appeared to reiterate the Cairo Embassy’s statement, announcing that “We reject all efforts to denigrate the religious beliefs of others,” in effect passing a value judgment on a certain instance of expression while failing to explicitly defend the principle of free expression itself.

Like the fury over the Muhammad cartoons in 2005 — which were published months before opportunistic imams whipped up an international (and deadly) controversy — clips from The Innocence of Muslims were put on YouTube in July this year. It was not until 9 September, however, that the Grand Mufti of Egypt declared that, “The attack on religious sanctities does not fall under this freedom,” the freedom in question being freedom of speech. Pointedly, the asinine US Embassy statement, while directly condemning shadowy American filmmakers, made no mention of the Egyptian Grand Mufti or other religious fanatics who had condemned the film and whipped people into such hysteria.

Like the fury over the Muhammad cartoons in 2005 — which were published months before opportunistic imams whipped up an international (and deadly) controversy — clips from The Innocence of Muslims were put on YouTube in July this year. It was not until 9 September, however, that the Grand Mufti of Egypt declared that, “The attack on religious sanctities does not fall under this freedom,” the freedom in question being freedom of speech. Pointedly, the asinine US Embassy statement, while directly condemning shadowy American filmmakers, made no mention of the Egyptian Grand Mufti or other religious fanatics who had condemned the film and whipped people into such hysteria.

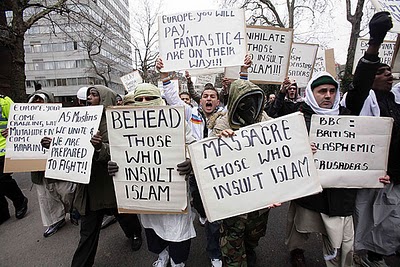

We are now treated to the strange spectacle of Western progressives aligning with Islamic religious reactionaries, both arguing that freedom of speech can go too far (of course, it is only speech that offends Muslims which comes under progressive suspicion; the same liberals who insist that the tender sensitivities of Muslims be respected have no problem with speech that maligns religious Christians and Jews). Those arguing that the YouTube clips that allegedly “incited” this mess should be banned – like the Guardian’s Andrew Brown – would do well to pause and consider the implications of what they are arguing. Does Brown think that Mitt Romney, a practicing Mormon, would be justified in demanding that the New York City authorities shut down The Book of Mormon? I am frequently outraged by what I read on the website of Brown’s newspaper (as one wag put it to me; “With Comment is Free, you get what you pay for”); would I be justified in expressing that anger through violence towards various and sundry Guardian writers?

Meanwhile, one can turn on the television or open a newspaper in any Muslim country and be sure to find grossly anti-Semitic material that is just as, if not more, offensive than anything contained in The Innocence of Muslims’ puerile script. Do American and British Jews then trek to the Libyan or Egyptian embassies in Washington and London, scale the fence, plant an Israeli flag on the roof, slaughter the ambassadors therein, and drag their remains through the street?

At least since the Rushdie affair, rioting and murdering over “insults” to religion has been a phenomenon almost exclusive to Muslims. It is strange, then, that those who insist the West must show more respect for Islamic civilization are precisely the same people who treat its adherents like children.

James Kirchick, a fellow with the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, is a contributing editor of The New Republic. He tweets at @jkirchick

Also read:

Kenan Malik on The Satanic Verses and free speech andWhy free expression is now seen as an enemy of liberty

Sara Yasin on France, Charlie Hebdo and the meaning of Mohammed

When we succumb to notions of religious offence, we stifle debate, writes Salil Tripathi

Sherry Jones on why UK distributors refused to handle her book The Jewel of Medina