The gas-rich country presents itself as open and modern, but Azerbaijan is not safe for activists and journalists fighting for free speech, says Natasha Schmidt

This year’s global Internet Governance Forum, where governments, industry and civil society join to discuss the future of the internet, will be held in Azerbaijan’s capital Baku from 6-9 November. Six months after Eurovision, it will give President Aliyev’s government another opportunity to present the mineral-rich state as a modern, outward looking country with investment opportunities for multinational corporations.

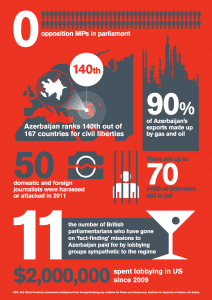

But the truth underneath Baku’s glitzy veneer is much darker. Azerbaijan is far from a democratic country: elections are not free or fair, journalists and civil society activists are consistently threatened with violence, harassment and imprisonment, and citizens’ access to independent, critical voices is severely limited.

The government has consistently made life difficult for investigative journalists and civil society activists who challenge government policy or interrogate business interests of the president’s family.

Recent arrests include that of Faramaz Novruzoglu, arrested on 23 August, who reported on government corruption. Novruzoglu, who also served prison sentences in 2007 and 2009, was sentenced to four-and-a-half years’ imprisonment on charges of illegal border crossing and inciting public disorder.

Public disorder and “hooliganism” charges are used by the Azerbaijani authorities to silence dissent and critical reporting.The 2009 arrest of “donkey blogger” activists Emin Milli and Adnan Hajizade was one of the country’s most prominent cases. As recently as 10 September, Araz Guliyev , who edits a website dealing with religious issues, was sentenced on hooliganism charges. On 13 June, photojournalist Mehman Huseynov was arrested on similar charges.

In April Index on Censorship award-winner Idrak Abbasov was brutally attacked by security guards working for Azerbaijan’s state-owned oil company SOCAR while reporting on the demolition of houses. Other journalists reporting on the incident were also attacked. The persecution of Abbasov and his family continues. As with so many attacks against journalists in the country, no one has been prosecuted for these acts of violence.

Imprisoned journalists also face intimidation and violence. Since his arrest in June 2012, Hilal Mammadov, editor-in-chief for Tolishi Sedo newspaper, has reported mistreatment and even torture. Mammadov faces life in prison on charges of high treason and inciting hatred.

In March, prominent investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova was the victim of a blackmail campaign. She received a collection of intimate photographs through the post, with a note warning her to “behave” or she would be “defamed”. Refusing to be silenced, Ismayilova — an important target not least because of her online activity — went public with the blackmail attempt. In retaliation, on 14 March an intimate video of Ismayilova filmed by a hidden camera was posted on the internet.

Ismayilova’s persecution sent a clear message to activists and independent journalists, further escalating the climate of fear that permeates much of Azerbaijani civil society today.

As in many countries, Azerbaijani civil society and independent journalism communities increasingly use the internet to galvanise change, spread vital information and news and discuss democratic and political change in the country.

As in many countries, Azerbaijani civil society and independent journalism communities increasingly use the internet to galvanise change, spread vital information and news and discuss democratic and political change in the country.

Roughly a third of the country — according to some reports, 27 per cent of the population — has access to the internet. According to one report there are over 36,000 internet users in Azerbaijan, with official figures citing over 13,000 domain names registered with the “.az” suffix. But only 19 per cent have access to broadband, meaning that the internet, though increasingly important for disseminating information, is not the first port of call for most Azerbaijanis.

As independent media finds itself threatened with violence, intimidation and lawsuits and without advertising revenue, the internet has become an important source of independent news. Azerbaijan’s media environment suffered a significant blow in 2009, when the BBC, Voice Of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty were banned from using the country’s airwaves. Online Objectiv.tv has become a reliable resource for news that goes unreported in mainstream media: in recent months, it has regularly reported on property demolitions taking place as part of the process of “beautifying” Baku.

Citizen journalism has played a key role, with mobile phone footage being used to document demolitions. In early 2011, in the wake of widespread protests in the Middle East and North Africa, the government clamped down on activists who used social media to organise demonstrations calling for democratic reform and improved human rights.

Azerbaijan’s citizens are not only deprived of their right to free expression, but their right to access information is also consistently under threat. Although FOI is enshrined the country’s Law on the Right to Obtain Information, in July 2012 President Aliyev launched an attack against investigative journalists, campaigners and even potential business investors by signing in amendments to the corporate disclosure law.

In late August, the state-owned printing house informed Azadliq newspaper that they would face eviction from their premises if they did not immediately pay a fee to them by early September. The paper now faces closure.

Defamation remains a criminal offence in Azerbaijan, despite repeated government claims that reforms are being considered. According to the Baku-based Media Rights Institute (MRI), in 2011, eight journalists were subject to criminal prosecution in defamation cases. This has led to widespread self-censorship in the country. MRI noted that the Yeni Musavat and Khural newspapers were the most frequent targets of these cases.

It’s clear that the Azerbaijani government and those close to it employ a huge range of tactics to silence critical voices, from intimidation and fabricated charges to clamping down on protest and blackmail.

Since President Aliyev came into power in 2003, a climate of impunity and a culture of self-censorship has ensued, making Azerbaijan a hostile environment for free expression and democracy.

Natasha Schmidt is Assistant Editor of Index on Censorship magazine. She tweets at @tasheschmidt